Excluded from Canada’s marijuana industry, Indigenous entrepreneurs are forging a sovereign market

From The Breach by Caitlin Donohue August 4 2022

When Tim Barnhart first opened a cannabis dispensary on Tyendinaga Mohawk territory back in 2015, it was considered a radical act.

Legacy 420 was a sovereign shop, promising to empower Indigenous communities by selling organic, medical cannabis products while operating outside of Canada’s colonial regulations,

Today, the bustling Legacy 420 is no longer the sole sovereign dispensary in Tyendinaga, much less in the country. Barnhart’s store has expanded as it’s thrived, and now features an in-house testing laboratory that guarantees product safety, not to mention a bakery that churns out custom cannabis-infused cakes.

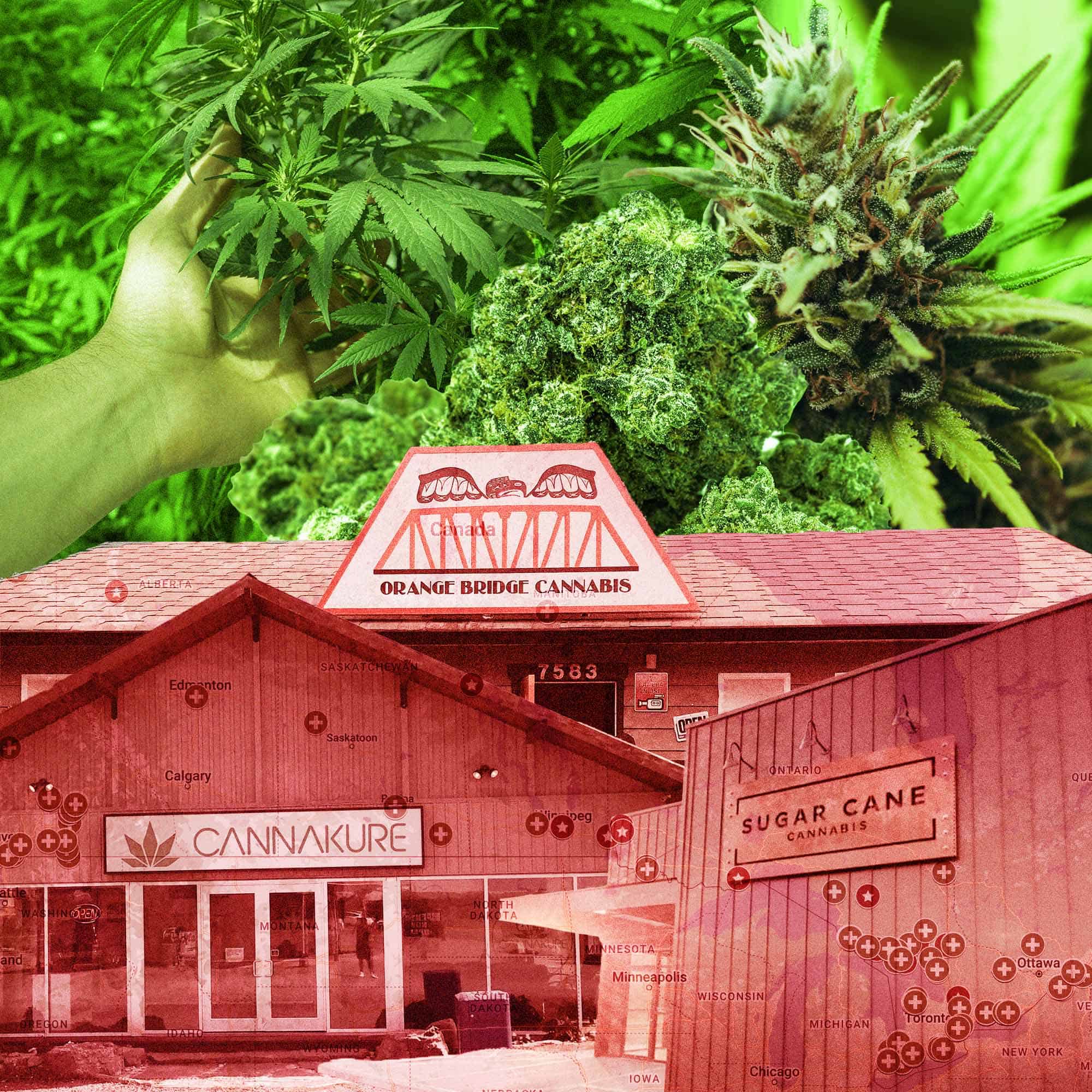

From the Miawpukek Cannabis Boutique on the coast of Newfoundland, to Orange Bridge Cannabis on the west coast of Vancouver Island, there are now an estimated 260-plus Indigenous-run cannabis stores in Canada, according to a map created by industry publication Dispensing Freedom.

Some, like Sugar Cane Cannabis in Williams Lake First Nation, are owned and run by band councils. Others, like The Way Forward Healing Centre in Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, are owned by individuals—in this case operating in the face of opposition from band leaders.

Ranging from completely-sovereign, to Canadian government-certified, and everything in between, these shops provide crucial financial support to their communities, from employment opportunities to funding for youth sports teams.

Functional differences aside, proponents of Indigenous cannabis agree the herb has become an important battleground in the fight for sovereignty.

Still excluded from the marketplace

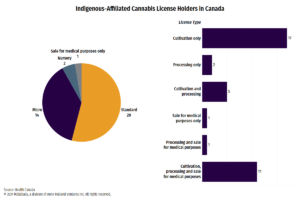

Since becoming the second country in the world to legalize recreational marijuana in 2018, Canada has emerged as the world’s top cannabis investor. But as Canadian corporations look to dominate markets across the globe, within the country’s borders Indigenous entrepreneurs remain excluded from its top-down cannabis regulatory system.

Even before the Cannabis Act came into force in 2018, the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples warned that Indigenous people were not being consulted in its drafting. Its passage enshrined Ottawa’s right to regulate cannabis production, while provincial governments would regulate retail—failing to grant First Nations jurisdiction over cannabis on their own lands.

Last year, the Assembly of First Nations demanded the federal government “recognize First Nations jurisdiction over cannabis and remove regulatory barriers that exclude First Nations from the marketplace.” But the wait for Ottawa’s long-promised review of the cannabis industry, which has the potential to better protect the rights of Indigenous producers and sellers, continues.

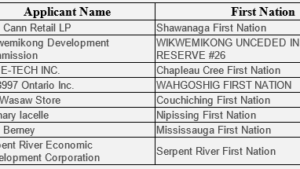

Only a handful of Indigenous cannabis companies in Canada have been certified by the federal government. Regulatory ambiguity has left most of these entrepreneurs on their own when it comes to structuring their marijuana businesses.

That’s why sovereign shops have come to occupy such an important role in Canada’s cannabis ecosystem, offering consumers products that aren’t allowed under rigid provincial and federal regulation.

Some sovereign shops and brands often find their growth severely limited due to lack of clarity around selling to non-Indigenous retailers, among other issues. They are also facing blowback from settler-owned cannabis retailers, 14 of which filed a lawsuit against the B.C. government in April alleging that the province’s failure to fully crack down on Indigenous-run sovereign shops had led to profit loss. Their move echoes calls for harsher policing of unregulated cannabis on the part of Canada’s largest marijuana firms.

As Indigenous groups stake their claims for post-prohibition cannabis profits, the fate of First Nations marijuana businesses within Canada’s borders—and their creative strategies for nation-to-nation power building in the weed space—are of global significance.

An employee at Green Devil Cannabis, owned by Clifton Ariwakehte Nicholas in the Mohawk community of Kanesatake. Photo: Green Devil Cannabis

Unregulated and unapologetic

For Clifton Ariwakehte Nicholas, the Kanehsata’kehró:non owner of the first cannabis store in Kanesatake Mohawk territory, the connection between Indigenous sovereignty and cannabis rights are clear.

When he was 18, he and his fellow community members put up resistance against a nearby settler town of Oka building a golf course on top of Kanesatake Mohawk burial grounds. Police invaded, Nicholas and others took up arms, and soon the army was brought in.

The 78-day standoff that ensued came to be known as the Oka Crisis, and is now considered a major modern-day flashpoint in the international struggle for Indigenous land rights.

“That conflict took away our naiveté about a lot of things,” Nicholas told The Breach. He began working in cannabis cultivation in his 20s, and discovered the plant’s therapeutic potential when he found that tea laced with CBD oil could treat his long-standing depression, which at one point had landed him in a psychiatric hospital.

He now spends his days making cannabis medicine available to his community and surrounding neighbours, and dreams of someday operating a “seed-to-sale” facility where the plant is grown, processed, tested, and sold under the same roof.

Like many Indigenous cannabis entrepreneurs, Ariwakehte sells products that are unavailable in licensed cannabis shops. On the shelves of his current store, Green Devil/Le Diable Vert Cannabis, are high-dose edibles prized by medicinal patients, cannabis extracts including Ariwakehte’s homemade hash, and products whose easy-open packaging is made with limited mobility customers and seniors in mind. He also shares information on opiate and cocaine addiction recovery with cannabis to his customers, a practice forbidden by Quebec law.

Nicholas hopes for more unity among the owners of the dispensaries that are located up and down the main road that bisects his community, and especially that his Band Council would take a more active role in overseeing Kanesatake’s cannabis industry. But when it comes to what his community does in its own territory, outside regulations and regulators are of little concern to Ariwakehte.

“We have the right to have our own economy, as long as it does not interfere with the laws” of Canada and Quebec, he said. “And I don’t consider that the cannabis that we sell interferes with the laws.”

Sage, seed paper, and sales limitations

Josée Bourgeois, an Algonquin artist and member of the Pikwàkanagàn First Nation is the brand development manager of AKI Wellness, a CBD topical line that forms part of the nation-to-nation distribution network Sweetgrass Trading.

The AKI Wellness line includes CBD-infused bath bombs, high-dose pain relief creams and gels, and skin care products crafted in Bourgeois’s community, as well as products incorporating plant medicines from the area, like cedar, sage, sweetgrass, and tobacco. They are packaged in sustainable materials that include seed paper that can be planted instead of thrown away after use.

But barring provincial certification, Bourgeois can only sell to other First Nation-owned cannabis companies.

“You know you have such a good product, and everybody and their grandmother is knocking on your door and asking for it,” Bourgeois said. She said she’s lost tens of thousands of dollars in potential sales due to a lack of federal regulatory clarity.

Sweetgrass Trading could potentially distribute the AKI products outside of First Nations communities with provincial certification—but that’s not the point, said Bourgeois.

“That’s like, ‘oops, sovereignty out the window,’ just because I can see the money,” said Bourgeois, who is also the community engagement manager for Sweetgrass Trading. “That’s what the work is. [The federal government] needs to adjust their policies so that we are not being judged as infringing on the law.”

When certification is seen as “selling out”

Other Indigenous groups have chosen to meet the Canadian government halfway on cannabis. The Williams Lake First Nation (WLFN) was motivated to get its marijuana business licensed by the B.C. government due to insurance needs, fear of police raids, and financing concerns.

The T’exelcemc embarked on the fitful path towards obtaining the province’s first government-to-government cannabis agreement—made possible by B.C.’s Cannabis Control Licensing Act—months before federal legalization hit. Their initial talks with B.C.’s solicitor general and the minister of public safety stalled when officials said they weren’t ready to start formulating regulations for Indigenous participation in the industry.

Instead, the First Nation partnered with Canada-wide cannabis cultivation and retail company Indigenous Bloom to open a sovereign shop in the city of Williams Lake. The location was eventually shut down, but Indigenous Bloom still operates nine other retail locations.

In 2020, an internal B.C. government mandate pushed the province to cede to some—if not all—of WLFN’s demands, including the fast-tracking of necessary permits and a “me too” clause that will make the band eligible for any privileges First Nations cannabis businesses may win in future negotiations with the province.

That same year, the WLFN broke ground on the $3-million Sugar Cane Cannabis farm-to-gate facility, subsidized by $500,000 from the B.C. government, and $250,000 from both Indigenous Services Canada and the Northern Development Initiative Trust.

Williams Lake First Nation’s Director of Legal and Corporate Services Kirk Dressler said the first-of-its-kind agreement did not win his team any popularity contests.

“Interestingly, we’re kind of seen as persona non grata by other Indigenous operators who are operating in the ‘red’ market,” Dressler told The Breach. “We’re seen as the sell-out community that’s folded to the province.”

Dressler sees the allowances as part of the province’s attempts at reconciliation. Even though the agreement does not include tax breaks or other ongoing financial leg-ups, he says that some non-Indigenous cannabis retailers think WLFN has been given unfair advantage over the rest of the market.

“From the perspective of other retailers, they assume that somehow we got this free pass, and that we’re made viable by virtue of this agreement, which isn’t the case,” he said. “They somehow see us as a spoiled child.”

Aside from seed funding, the advantages of the agreement were minimal, according to Dressler.

Williams Lake First Nation is now planning to open four locations of its retail brand, Unity Cannabis. These stores will only be allowed to fill 50 per cent of their stock with Sugar Cane Cannabis products. The rest of their offerings will come from the government’s BC Liquor Distribution Branch stock, products that are widely available in dispensaries throughout the province.

Sugar Cane products will also be available to the province for wholesale purchase, and will likely be featured in BC’s recently-launched program that promotes Indigenous-made cannabis.

The road has been a bumpy one, but Dressler said he wouldn’t choose to continue operating without provincial certification if he could do it over. But he does think B.C. would do well to reconsider its approach to doing business with Indigenous cannabis producers if it wants more First Nations to follow the “well-resourced” course taken by the T’exelcemc.

“A lot of communities are watching very carefully what we’re doing,” said Dressler. “They’re seeing this huge amount of money that we spent, and the huge amount of effort that we’re putting in.”

Serving customers in the face of criminalization

Williams Lake First Nations’ Sugar Cane Cannabis could be seen as a cautionary tale due to the time and cost involved and the sparse government support that resulted. But others have been inspired by its model, as was the owner of cannabis store Best Buds Society in Regina, Saskatchewan.

As a Métis person, and unlike First Nations peoples living on reserve, Pat Warnecke could not rely on the government’s recognition to protect his shot at running a weed business. The then-member of the Regina Riel Cresaultis Metis Local #33 applied to Saskatchewan’s 2013 medical marijuana commercial license lottery, which gave them a very small chance of getting a license.

Disillusioned with the system, Warnecke opened the doors of the first Best Buds Society location near Regina’s North Central neighbourhood in 2015 without provincial certification. It was so successful that he soon had five dispensary locations, which provided tested cannabis products to more than 12,000 patients. He also worked as a consultant for the Muscowpetung First Nation in the opening of its now shuttered Mino-Maskihki “Good Medicine” Cannabis Dispensary.

“We did everything by the books,” Warnecke told The Breach. “We paid our taxes. We had all of our workers take a nurse’s level cannabis course to work for us. All patients had to have a prescription. We had a pretty good thing going.”

Just three months before the passage of the Cannabis Act, Best Buds became a target of a Regina Police sweep of unlicensed cannabis stores. The next day, Warnecke vowed to re-open—and was raided again that evening. He soon had to leave his position with the Métis council. The cops put out a warrant for Warnecke and then-girlfriend Megan Potter’s arrest, launching a much-publicized “search” that ended when the two turned themselves in.

Today, Warnecke is fighting trafficking and possession charges while his team at Best Buds continues to get cannabis medicine to Regina residents as best as it can. He says what has upset him most was the opioid overdoses occurring among their clients who also use heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines.

“Half these guys were staying off [harder drugs] because they were eating a gram of cannabis oil every day,” said Warnecke. “All of a sudden, they don’t have access to it, we’re not open, people started losing their minds.”

His patients’ legal challenge is currently being heard by the Court of the Queen’s Bench in Regina, where Warnecke’s team is arguing that Best Buds had a right to supply medicine to its largely low-income, Métis, and First Nations clientele, which they say have been poorly served by Health Canada’s regulations. Warnecke says the monumental patient’s rights cases of Smith (2015) and Allard (2016) set legal precedence for his own claims.

While he waits for the court’s verdict, Warnecke is starting a company that makes dabbing thermometers that protect consumers from under-heating or singeing cannabis concentrate. Against all odds, he’s not planning on leaving the marijuana space.

“I think cannabis is the fight of our generation,” he said. “The stakes are inclusivity in the economy and market, development of business and the community and entrepreneurship, on First Nations land.”

Towards a ‘red’ cannabis market

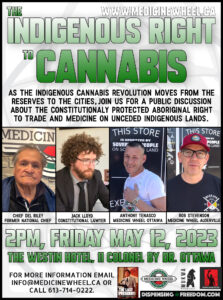

As Indigenous cannabis entrepreneurs assert their space in the industry, many are looking to create a more inclusive future. Rob Stevenson, who is Anishinaabe and a member of the Bear Clan, founded Medicine Wheel Natural Healing in Alderville First Nation in 2017. He’s convinced unity among Indigenous people is the way forward.

Well before federal legalization, Stevenson’s shop was the first on Alderville’s “Green Mile”—a street now lined with sovereign cannabis stores. By the fall of 2018, it was reported that one-fifth of Alderville’s residents were employed by the cannabis industry.

Medicine Wheel, which now serves more than 60,000 patients, operates in a hybrid model: it is completely sovereign at the same time as it complies with federal regulations. Stevenson is seeking provincial certification for his on-site Red Feather Labs, which currently tests both his own products and those of his Red Road Trading distribution network for contaminants and cannabinoid percentages.

Formerly involved with community policing in Alderville, he’s also taken steps towards ensuring greater local control of the industry. Stevenson and other area cannabis entrepreneurs formed the Mississauga of Rice Lake Cannabis Association, which provides crucial input to their Band Council on cannabis regulations.

“I see Medicine Wheel as a tool to strengthen our sovereignty, to strengthen reconciliation, while minimizing the effects of colonization,” Stevenson said.

Stevenson takes inspiration from Indigenous leaders like Chief Del Riley, a Hereditary Chief and former chairperson of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples who helped to draft sections 25 and 35 of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which affirm existing treaty rights and foundations. Riley has subsequently emerged as an important advocate for cannabis sovereignty, and tours First Nations supporting the rights of Indigenous entrepreneurs.

“We don’t have to prove anything to anyone,” Riley told Dispensing Freedom, when asked last year whether cannabis is an Indigenous right. “On the other hand, they have to prove to us how they acquired any sort of rights over us without ever discussing it. That is the first hurdle that has to be overcome.”

Last year, Stevenson founded a nation-to-nation Indigenous cannabis distribution network called Red Road Trading. It currently works with around 15 First Nations and Indigenous dispensaries, stocking them with products from brands like the high-end extractions line Indigenous Cannabis Revolution, and woman-run CBD topicals line GiiD.

Red Road’s products are certified by Red Feather, ensuring that they are pesticide-free and that “the majority of the ingredients of a given product were sourced and manufactured Indigenously,” according to Medicine Wheel’s website.

All of this work aims to create change for Indigenous growers, sellers and users of marijuana, and break with colonial and corporate cannabis in Canada, Stevenson said.

“I want to support a ‘red’ market.”

Comments are closed.