Algonquin Amikwa Anishinaabek (Beaver People) living in Reserves #13 and #2 as described by the 1854 Rowan Proclamation and the 1850 Indians’ Protection Act are waging a legal battle to defend the Indigenous right to grow and trade cannabis.

From Dispensing Freedom, Issue 1

FRENCH RIVER – Located along the Northern shore of Georgian Bay and along the Pickerel River are three parcels of land “reserved for Indians” lived upon by non-treaty members belonging to the Algonquin Amikwa Anishinaabek nation and non-treaty members of the Potawatomi Anishinaabek Nation, with over 150 of them living on these reserves, and at least 600 more living elsewhere.

The Amikwa people have occupied the strategically important Lake Superior, Lake Huron and French River, Lake Nipissing, and Ottawa River water system and been influential traders since time immemorial. Historian Diamond Jeness notes that during the heyday of the fur trade, “the Algonkians probably derived less profit from their furs than from the sale of medicines.” The Amikwa most likely encountered European goods well before French explorers like Étienne Brûlé and Samuel Champlain visited their territory in the early 1600s.

The Amikwa of Reserve #2 and Reserve #13 currently have a small economic footprint, but that is starting to change. Over the past several years, two small Indigenous cannabis shops – Medi Shack and New Age Medicinals – have opened up on the territory and have been selling a variety of cannabis products to passer-bys on Highway 69, the section of the Trans-Canada highway that connects Sudbury to Hwy 400.

Canada’s Cannabis Act makes no provision for Indigenous people and was pushed through without consultation or regard for Indigenous rights. By opening – and staying open despite police raids – the shops in Reserve #2 are taking part in an Indigenous cannabis revolution that is sweeping across Canada, and that now numbers over 160 documented Indigenous dispensaries operating outside of Canadian law and jurisdiction.

The illegal police raid

On Friday, January 4th, 2019, the two Reserve #2 shops were raided by the Provincial Joint Forces Cannabis Enforcement Team, a multi-agency police force co-ordinated by the OPP for the purposes of cracking down on “illegal” cannabis dispensaries. According to a press release issued after the raid, police seized $157,230 worth of cannabis products and $3,250 of Canadian currency from New Age Medicinals. Police also seized suspected cannabis bud, hash and edibles with an estimated street value of $33,730 and $229 in Canadian currency from Medi Shack. The OPP claimed that the raid was necessary in order to “dismantle organized crime groups, eliminate the illegal cannabis supply, remove illegal cannabis enterprises such as storefronts and online, and target the proceeds of crime and assets.”

A number of non-treaty Amikwa nation members (David Brennan, Jessie McAvoy, and Neil Herbert) were charged under the provisions of the Cannabis Act for “possessing cannabis for the purpose of selling,” and “allowing property to be used for unlawful sale or distribution under the Canada Cannabis Act.” Not surprisingly, these Indigenous cannabis entrepreneurs see the matter quite differently from the arresting police officers. They hold that they’ve done nothing wrong in selling cannabis on their land, and that they were robbed by police who violated their Indigenous rights and who have zero jurisdiction to even be on their territory.

On August 8th, 2019, the accused Amikwa people gave Her Majesty the Queen a Notice of Constitutional Question, and requested that the charges brought against them on behalf of the Queen be stayed. They assert that as the original titled Indigenous people of this land, they have every right to legally trade cannabis amongst their people and with visitors to their territory. Represented in court by lawyer Michael Swinwood of Elders Without Borders, the three non-treaty men have joined with another non-treaty Amikwa woman charged on an unrelated cannabis charge on the territory to bring their cases together and jointly put forward their Constitutional Question.

The purpose of raising a Constitutional Question is to inform the Queen that “the constitutional validity, applicability or effect” of a particular legislative provision made by the Canadian Parliament violates a matter of fundamental justice or law. In this case, the issue is about the relationship between the non-treaty Algonquin-Anishinaabe people, and their lack of agreements and treaties of peace and friendship between the peoples and Canada stemming from the actions of the British Crown and its Canadian subjects.

In cases where laws such as the Cannabis Act violate the underlying constitutional framework of the British Crown in Canada, they are set aside or overturned by the courts. In this case, the Amikwa nation members argue that the enforcement and imposition of the Cannabis Act on their traditional territory is unconstitutional because it violates their constitutionally protected rights which were recognized by the Crown long before Canada even became a country and which are upheld in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The case of the Amikwa in the Rowan Proclamation reserves is all the more significant because the constitutional arguments it makes directly relate to a host of other dispensary raids carried out by the OPP’s PJFCET in several other Indigenous communities, including the January 3, 2019 raids of First Nations Medicinal and Creator’s Choice in Wahnapitae, the September 18th 2019 raids of First Nations Medicinal and Creator’s Choice in Wahnapitae, and the November 27, 2019 raid in Garden River First Nation. So far eight of the Indigenous cannabis entrepreneurs in these communities have joined the Constitutional challenge being raised by the Amikwa.

The Constitutional Question

The Constitutional Question raised by the Amikwa in reserve No. 2 and No. 13 argues that the Cannabis Act charges on their people violate four sections of the Canadian Constitution as well as nine articles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP). The constitutional rights in question are: Section 25 “Other rights and freedoms”; Section 26 “Guarantee of “Other rights and Freedoms”; Section 35 which “recognizes and affirms” the “existing Aboriginal and treaty or Other Rights or Freedoms”; Section 7 rights relating to “Life, Liberty, Security of the Person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice”. Other issues raised in the challenge also include Canada’s “Duty to Consult” and the issue of “Genocide and Apartheid” the Bench of a Canadian Court has agreed to consider for the first time.

The articles of UNDRIP that the Amikwa claim the OPP violated include: Article 3 which states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination” and the right to “freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development”; Article 4 which states that “Indigenous peoples, in exercising their right to self-determination, have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions”; Article 5 which states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions”; Article 6 which states that “Every indigenous individual has the right to a nationality”; Article 7 (1) which states that “Indigenous individuals have the rights to life, physical and mental integrity, liberty and security of person”; Article 7 (2) which states that “Indigenous peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace and security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide or any other act of violence”; Article 10 which states that “Indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories”; Article 12 which states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practise, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies”; and Article 24 which states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals and minerals.”

In addition to the Canadian Charter and UNDRIP, the case cites the 1948 UN Convention on Genocide, the Crimes Against Humanity Act and War Crimes Act, and reports from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls as statutory provisions or rules upon which the applicants will rely.

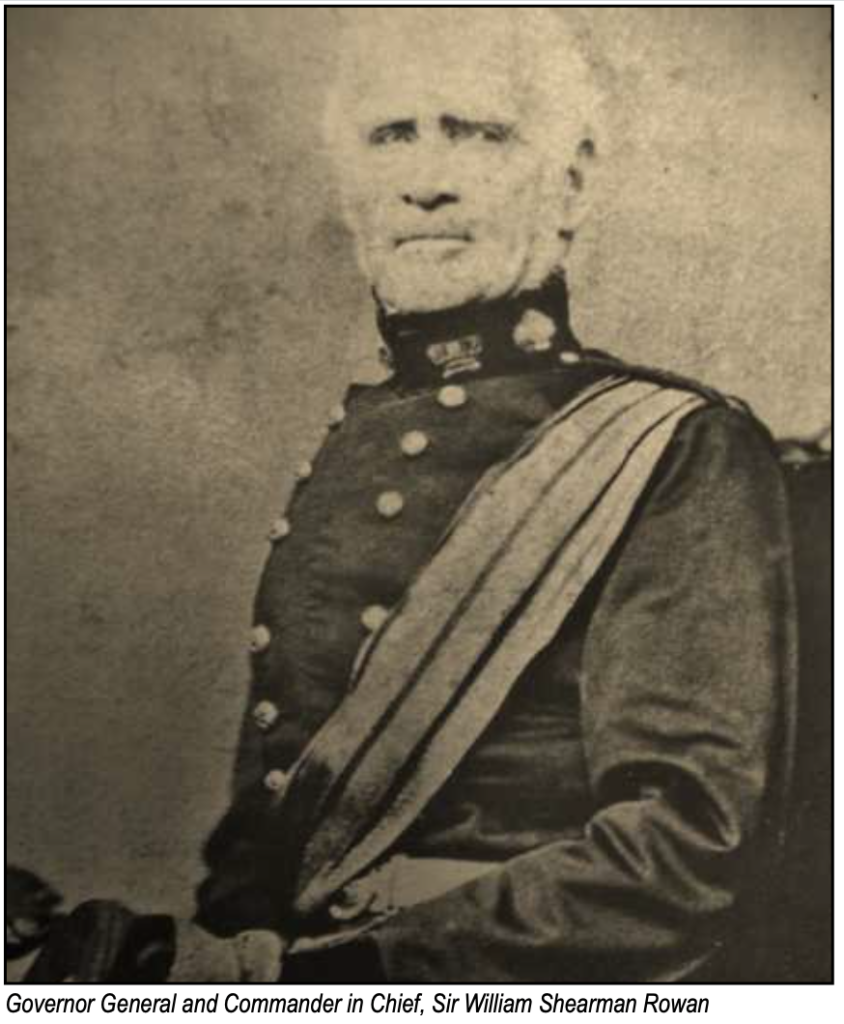

Rowan Proclamation and the Indians’ Protection Bill

Of special relevance to the Constitutional question are the Rowan Proclamation of March 11, 1854 and the Indians’ Protection Bill of July 30, 1850. The Rowan Proclamation was made in 1854 by Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America Sir William Shearman Rowan and has the same legal weight as a Royal Proclamation. The Indians’ Protection Bill was passed four years earlier by the Upper Canada Legislature as a means of addressing the trespassing and injury being caused within Indigenous jurisdictions by unscrupulous European squatters.

The Rowan Proclamation explicitly outlines various Indian lands “on the borders of Lake Huron, Superior, Nipissing and Nipigon” where the provisions of the “tenth, eleventh, and twelfth sections” of the Indians’ Protection Bill should be explicitly applied. These sections concern the protection and possession of Indigenous wealth and property, and the means for removing and punishing the European immigrants squatting on their land. The lands in question are 20 parcels of land described in the Rowan Proclamation which were later designated under the Indian Act as reserves.

These lands include the territories currently associated with and known as listed with Rowan Proclamation Numbering, Magnetawan First Nation No.1, Henvey Inlet Indian Reserve No. 2, Point Grondine Indian Reserve No. 3, Whitefish River First Nation No. 4, Sagamok Indian Reserve No.5, Whitefish Lake No. 6, Serpent River First Nation No. 7, Mississagi River No. 8, Dokis First Nation No. 9, Nipissing Indian Reserve No. 10, Wahnapitae First Nation No. 11, Thessalon Indian Reserve No. 12, French River Indian Reserve No. 13, Garden River Indian Reserve No. 14, Batchewana First Nation No.15, Parry Island First Nation No.16, Shawanaga First Nation No. 17, Fort William First Nation No.18, Michipicoten No.19 and Gull Bay First Nation No. 20.

The purpose of the Indians’ Protection Bill was two-fold. First, to protect Indians and non-Indians who had intermarried with Indians, on these lands by declaring their personal wealth and property inviolable from “designing and unprincipled” settlers. Indians using modern and “civilized” forms of wealth and agriculture were especially protected under this bill. And secondly, to “provide more summary and effectual means for the protection of sùch Indians in the unmolested possession and enjoyment of the lands and other property in their use or occupation.”

These issues had long been matters of concern to Indians facing an influx of European immigrants, which grew by 800,000 in the years between 1815 and 1850. The Indians’ Protection Act re-iterated many of the same basic positions in Crown-Indian policy as defined in the 1763 Royal Proclamation. The Act stated that no purchase or sale of land from Indians could occur without the “authority and consent” of the Crown; that no person could sue any Indian in Upper Canada unless it was over land held in “fee simple” ie. personally owned and alienable land within the British landholding system; that “no taxes shall be levied or assessed upon any Indian or any person intermarried with any Indians” who lived on Indian land; that no tolls or fees would be charged on any “road, bridge or ferry” in the Province; that no “spirituous liquors” could be sold to Indians; and that any property pawned by Indians in exchange for alcohol must be returned to them.

In making his Proclamation, Governor General William Rowan underscored three specific sections of the Indians’ Protection Act – X, XI, and XII – that protected Indians and punished unwanted intruders and tied specific parcels of Indian land to these protections. In so doing, the Governor General was acting as the direct embodiment of the Crown and upholding its duties to its Indian allies, and was continuing in the footsteps of a long established relationship between the Crown and Indians in the Great Lakes region.

Section X of the Act explicitly protects the wealth of Indians from seizure – including their treaty annuities and presents – as well as Indian wealth expended and invested in “the encouragement of agriculture and other civilizing pursuits” i.e. in growing and selling their produce and wares from within their own economy. The Act recognizes the individual rights of Indians to hold this wealth which “may be and often necessarily are, in the possession or control of some particular Indian or Indians of such Tribes.” The Act also explicitly protects Indian held property from “seizure, distress or sale, under or by virtue of any process whatsoever.”

Section X goes on to clarify that “none of such presents or of any property purchased or acquired with or by means of such annuities or any part thereof, or otherwise howsoever, and in the possession of any of the Tribes or any of the Indians of such Tribes shall be liable to be taken, seized or distrained for any manner or cause whatsoever.”

Section XI of the Indians’ Protection Bill gives Justice of the Peace powers to the Commissioners and the different Superintendents of the Indian Department so that they are better able to remove squatters on Indian Lands.

Section XII explains that the giving of these “summary and effectual powers” to the Commissioners will afford “better protection to the Indians in the unmolested possession and enjoyment of their lands.” Section XII states that these Acts “enable [Indians] more efficiently to protect the said lands from trespass and injury, and to punish all persons trespassing upon or doing damage thereto: Be it therefore enacted, That it shall not be lawful for any person or persons other than Indians and those who may be intermarried with Indians, to settle, reside upon or occupy any lands or roads or allowances for roads running through any lands belonging to or occupied by any portion or tribe of Indians within Upper Canada.”

The Constitutional Question notes that “The Rowan Proclamation continues to be in force, and has never been revoked. Along with the Royal Proclamation of October 7th, 1763, the land upon which the said offence was alleged to have been committed, is unceded Indigenous territory and is protected from imposition, trespass or injury by others. Together these Proclamations deprive the Crown of jurisdiction.”

The Constitutional question further asserts that the place where the raids took place on the Reserve No. 2, or the Reserve No. 13 does not actually belong to the Crown or its Indian Act Band, but is rather “the traditional unceded land of the Algonquin Amikwa Anishinaabek Nation.” This raises a whole other question concerning the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850, a treaty that the Amikwa people in court view as Void Ab Initio, Latin for “to be treated as invalid from the outset.”

On its surface, the Constitutional Question raised by the Amikwa in these raids seems pretty open and shut. A Royal Proclamation with the force of law explicitly protects the economic activity of Indians to engage in such “agricultural and civilizing” activities as cannabis growing and sales on their own lands – free of taxation, seizure, and Crown control.

To the extent that any law officers accountable to the Crown are operating on these Indigenous territories, they should be evicting non-native squatters, not robbing and intimidating non-treaty Indians engaged in their own economic development on their own unceded lands. The argument being raised in Reserve #2 and Reserve #13 could be raised in all the other 20 different territories identified in the Rowan Proclamation, if not within the balance of its Unceded traditional territory a whole.

For more information about the case and the history of the Amikwa, visit www.beaverbowl.org.

Comments are closed.