Wednesday’s recreational weed legalization sets the stage for a complicated clash on some First Nations, pitting Indigenous self-governance rights and social policy against federal legislation and economic promise

From winnipegfreepress.com link to article by Alexandra Paul

October 14th 2018

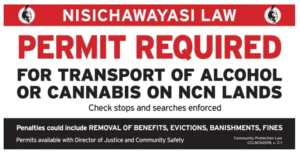

First Nations across Canada have banned or restricted the flow of alcohol for years.

It’s a legal power they hold through the federal Indian Act, which allows First Nations to ban the sale, purchase and possession of alcohol or any other intoxicant. To pass, a bylaw requires a vote of 51 per cent of residents who attend a meeting called for the vote. It comes into effect as soon as the local chief and council enact it and a copy must be mailed to Ottawa within four days.

First Nations that govern their affairs outside that legislative framework enjoy similar jurisdictional powers. It’s also common practice to search and confiscate contraband from baggage when planes land in remote or isolated First Nations. There’s even a name for them — dry reserves.

In the days leading up to Oct. 17, the date when marijuana will become legal in Canada, it’s unclear if First Nations have the legal right to ban pot possession.

Efforts to determine what position Manitoba dry reserves are going to adopt have been unsuccessful, despite repeated calls to various levels of the federal government, police and Indigenous organizations.

Politically and administratively, it seems certain some First Nations will quietly ban pot anyway. Then it will be up to Ottawa to decide whether to make a court issue out of it or not.

Federal Liberals have focused their political efforts on carving a path to strike a balance between twin political priorities that could clash — Indigenous governance and the right to ban distribution of an intoxicant that’s about to be legal.

Spokespersons with Carolyn Bennett’s Crown-Indigenous Relations and Jane Philpott’s Indigenous Services departments made a point of deferring to Health Canada on the file.

“Throughout the legalization and regulation of cannabis, the government has placed a high priority on Indigenous interests,” a spokesperson with Health Canada said in an email to the Free Press.

Framing the legalization of pot as a health issue isn’t new; Prime Minister Justin Trudeau relied on the same strategy for public support during the 2015 election campaign.

Securing Indigenous support has also meant a lot of work behind closed doors, however.

Ottawa created a special task force on legalization and regulation of pot on First Nations, Health Canada said, which included setting up a team of government experts to work with Indigenous communities on ways to set up regulations around pot after Wednesday’s legalization.

The process rolled out a year ago, and since then officials have held 70 separate meetings across the country with Indigenous leaders, communities and organizations, including the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs.

The crossover between federal and Indigenous interests on pot has also drawn the attention of Canada’s lawyers, who so far seem to be taking a wait-and-see attitude.

They are also aware some First Nations see legalization as an economic opportunity. Others will focus on substance abuse and some, particularly dry reserves, may ban it all together.

In Manitoba, expect all three scenarios to roll out.

Onekanew (Chief) Christian Sinclair of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN) positioned The Pas-area community as the first Indigenous group to be the largest private shareholder of a cannabis clinic chain. OCN holds 10 per cent of the shares in the Ottawa-based National Access Cannabis Corp. (NAC).

Sinclair described how Manitoba First Nations hashed out their positions in a recent meeting.

“In that regard, the issue came up at the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs last summer… and the vote came down that every First Nation has the right to decide to do what it wants and we will respect that,” Sinclair said.

“If someone comes into one of our storefronts, and they’re legal, we’ll sell to them… it’s up to that individual to deal with the bylaws of his own community. But we’re not going to go to a First Nation we know is a dry reserve and say, ‘Hey, can we (set up a dispensary here)?’ We’ll respect that.”

In business terms, Indigenous law and pot laws might come into conflict, but they needn’t clash.

“It’s very simple. We recognize First Nations are sovereign,” Sinclair said.

Communities such as Sinclair’s OCN welcome marijuana sales as a new source of revenue. NAC announced plans earlier this year to open up storefronts in what he called the big five First Nations of Manitoba— OCN, Nisichawayasihk, Long Plain, Peguis and Brokenhead.

“It’s a public commodity now. Let the free market reign,” Sinclair said.

If there’s a counterbalance, it’s regulation.

That’s the message coming out in stereo from Health Canada and from cabinet ministers in recent hearings before a Senate committee.

“Let me be clear… it would not be a federal offence to possess cannabis in (a dry reserve) community because the federal law, the Cannabis Act, has repealed that, and made it possible for people to possess it,” Bill Blair, minister of border security and organized crime reduction, said in response to questions put to him by Manitoba Sen. Marilou McPhedran earlier this month.

Blair and his cabinet colleague Philpott appeared before the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples Oct. 3 to answer questions about the impact legalization will have on Indigenous communities.

“But there are other aspects of that law that also apply to banning it under certain ages and in certain amounts,” Blair added. “It’s entirely possible, I believe, for a community to pass additional restrictions as long as it’s not frustrating the intent of the act.

“Quite frankly, I’m not inclined to tell them they cannot do it, but a court could determine that it frustrates the intent of the act.”

Pressed on whether Ottawa would take a First Nation that banned cannabis into court, Blair said it was unlikely.

“My understanding is the minister of justice has made it clear that she does not intend to litigate on that issue,” Blair said.

alexandra.paul@freepress.mb.ca

Comments are closed.