By David Brown, Stratcann, May 13, 2021

A First Nations-owned cannabis producer in Ontario has expanded its distribution to First Nations retailers in BC this week.

The products, grown by Seven Leaf, a Health Canada licensed producer operating in the First Nation territory of Akwesasne, are being shipped following a release of products in April to a retailer in Ontario who is licensed to operate by the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne.

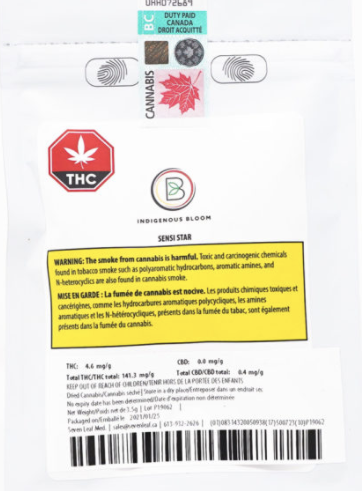

The BC-based Indigenous Bloom chain of retailers first began listing two different products grown by Seven Leaf in their online store earlier this week. Although currently no longer listed online, a manager at one Indigenous Bloom location in Osoyoos, BC, confirms they have received three different strains of dried flower from Seven Leaf that they expect to have on shelves soon.

Several other Indigenous Bloom locations have confirmed they are also carrying the product. The product that was listed on the Indigenous Bloom online marketplace showed a BC cannabis excise stamp and lists Seven Leaf Med on the packaging.

The move represents a significant step for a federally licensed cannabis producer, as neither Green Chief Naturals, the cannabis retailer on Akwesasne territory, nor Indigenous Bloom are licensed to sell cannabis by their respective provincial authorities.

Canada’s Cannabis Act and Regulations provide the authority to regulate the sale of cannabis to provinces and territories, and both Ontario and BC, as well as the federal government, have all said that their own respective cannabis regulations are laws of general application, meaning they apply to all areas in those jurisdictions, including Indigenous land.

Many Indigenous communities in Canada have disputed this interpretation, saying they have the right to manage cannabis as they see fit. The Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB), where the aforementioned Indigienous Bloom operates, first passed a moratorium against any cannabis stores in their community in 2019. The community then adopted their own Osoyoos Indian Band Cannabis Bylaw in 2020, citing section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 which recognizes and affirms the existing aboriginal self-government and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada.

Unlike Green Chief Naturals in Ontario, Indigenous Bloom is not licensed to operate in their local community. Representatives from Indigenous Bloom and the OIB were unavailable for comment as of press time. In 2019, the company lobbied the federal government around the issue of amending policies under the Cannabis Act as they pertain to First Nations communities.

The OIB’s corporate plan for 2018-2022 includes their intention to open “a new legal marijuana growing facility” and new marijuana retail outlets.

The band licensed their first retailer in September 2020, Timix’w Wellness. The Indigenous Bloom location is not currently licensed by the OIB. The owner of Timix Wellness, Corey Brewer, also runs a dispensary called Tupas Joint that operates in Vernon, BC that was raided by BC’s Community Safety Unit (CSU) in 2020, but did they did not raid Brewer’s store on First Nation land.

Brewer, owner of Tupas Joint in Vernon, told the media earlier this year that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, implemented in BC, gives him the right to do business without a license. However Yvan Guy Larocque, a Vancouver-based attorney who specializes in Indigenous law, says Indigenous self-determination rights as set out in UNDRIP are collective rights, not individual rights as Brewer suggests.

In 2020, BC’s Minister of Public Safety and Solicitor General Mike Farnworth said the province does not recognize such sovereignty in regard to federal and provincial cannabis regulations, but they are hesitant to enforce their law on First Nations territory out of fear of a court challenge.

“With cannabis, like a number of other issues when it comes to First Nations, our view, the province’s view, is that yes, they are laws of general application,” said the Minister. “Just as with some other issues, First Nations have said, ‘No. These are areas of our jurisdiction,’ and that’s both at the provincial level and at the federal level.

“On numerous occasions, these are often tested in court, sometimes with a decision that, yes, they do come under First Nations jurisdiction, and that has far-reaching effects.

“When you have an issue where there is a dispute over jurisdiction, as a number of First Nations have indicated,” continues Farnworth, “it is their view that cannabis comes under their jurisdiction. This is a complex and complicated situation. It is something that has not just arisen. It has been around for a while, and we are working with First Nations to be able to deal with that. It’s why one of the ways in which we are encouraging legal production or legal retail is through the use of Section 119 agreements under the Act, which were designed to do just that.”

The province has been actively working with several BC cannabis producers through these Section 119 agreements to encourage communities to comply with federal and provincial law.

A representative for the CSU provided this statement to StratCann last year:

“The Province acknowledges that some Indigenous nations may have differing views with respect to federal and provincial cannabis frameworks, and recognizes that there is uncertainty associated with any court case. The Province is also committed to reconciliation, building positive relationships with Indigenous governments, understanding where they have different perspectives, and, where possible, collaborating to find resolution. These efforts are balanced against the need to ensure that the legal and regulatory framework for cannabis is implemented across the province and in alignment with federal laws.”

“The CSU works to make connections with Indigenous communities and considers their views and interests when carrying out compliance and enforcement activities, including reaching out to build relations with Chief and Council.”

In 2020 the CSU says they visited over 270 unlicensed retailers “for the purposes of education and to raise awareness about cannabis laws and the penalties and consequences for violating federal and provincial regulatory regimes.” The CSU says they followed up with enforcement action on at least 47 occasions as of August 2020 against unlicensed retailers that chose to continue to operate without a licence after the initial education visits, and over 90 unlicensed retailers have either closed or stopped selling cannabis as a direct result of the CSU’s actions.

A request to Health Canada was made on this issue and this article will be updated with their reply. A report from the Minister of Health and the Minister of Indigenous Services from 2018 noted that the Government had adopted “a novel and flexible approach to engaging with Indigenous peoples, which focuses on the specific interests and objectives identified by individual communities”.

The report continues, in part: “…officials have been working with many leaders and their communities as they finalize their own regulatory frameworks, to consider how these will interact with federal and provincial or territorial laws and regulations, and whether collaboration opportunities exist to support the implementation and enforcement of these community-level regulations. Engagement has also taken place with community leaders that are seeking to address unauthorized and unregulated activities on their lands, and to collaborate on finding solutions to ensure that activities with cannabis take place in a way that does not pose risks for the health and safety of community members. This engagement could form the basis for developing partnerships that could serve to test new models or approaches by which communities can exercise greater control over activities with cannabis, supporting both self-determination as well as our shared objectives of protecting public health and safety and displacing the illegal market. The Government is committed to continuing to engage with interested Indigenous communities, in collaboration with provincial and territorial governments where there is willingness and commitment to do so or bilaterally if necessary, to advance these objectives.”

The issue also raises questions about compliance for other Health Canada licence holders.

Jeannette VanderMarel, President of Pharmhill Inc, a Health Canada licensed producer in Ontario, says she’s supportive of Seven Leaf’s move to sell products to First Nations retailers, but has concerns about an uneven playing field when it comes to Health Canada’s enforcement of federal rules about where licensed cannabis producers can sell products.

VanderMarel is also the former CEO at Beleave Inc, former CO-CEO of 48 North, and Co-Founder of Good & Green and TGOD, all Ontario-based licensed cannabis producers under Health Canada’s regulations.

“I strongly support First Nations communities, and was heartened to hear of Seven Leaf’s licensing,” writes VanderMarel via email. “Further, Pharmhill is exploring a white label opportunity with a First Nations group to sell cannabis products to provincially licensed dispensaries across Canada.

“Until the gaps in the Cannabis Act and provincial distribution models are appropriately adjusted to accommodate First Nations rights to self-determination, I can only imagine these actions may have a chilling effect on potential collaborations for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous cannabis LPs and retailers. Clarity is required to ensure we are on a level playing field for all licensed producers and licensed retailers.

“We at Pharmhill respect the rights of First Nations sovereignty on their lands. We strictly follow the Cannabis Act, Ontario provincial regulations, and our municipal regulations to ensure we are a good corporate citizen. An uneven set of rules, or the rules being applied differently for Indigenous and non-Indigenous licensed producers, may lead to further challenges for our burgeoning industry.”

In an interview from 2019, Lewis Mitchell, president and part owner of Seven Leaf, said he and the company are committed to operating according to federal law. The federal Cannabis Act only allows licensed cannabis producers to sell into provincially and territorially authorized retail channels. Although Ontario has several licensed cannabis retailers on First Nations Land, Green Chief is not one of them, instead operating under the regulations of the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne.

Seven Leaf has not responded to several media requests made by StratCann over the past month on this topic.

Sara Mainville, a partner with Olthuis Kleer Townshend, a law firm that works with Indigenous communities, told StratCann in April that this is a complex and ongoing political and legal issue that touches on First Nations sovereignty and how it interacts with provincial and federal jurisdictions in Canada.

“The fact that First Nations are asserting their laws supersede provincial law, that is political as it is legal,” says Mainville. “But there are definitely some legal arguments to be made that a provincial authority can be ousted, particularly with an interpretation of both the Indian Act and recent case law that’s coming out of the federal court around an exercise of inherent jurisdiction by First Nations communities,”

Although she says she thinks there could potentially be a strong legal argument to be made for a cannabis producer to distribute to a retailer within the same First Nations community, to ship outside that community would likely be a more difficult argument to make in court.

“I’m hopeful that they’re getting legal advice around this because it’s difficult going outside of your jurisdiction,” continues Mainville.

“Once these products leave a First Nations reserve, then how do you maintain First Nations jurisdiction in the territory outside? I’m sure that there are strong Mohawk legal arguments for a much broader territory than the reserve itself. I’m certain that exists. But certainly some of the trade and commerce commitments made in treaties, including the 1764 treaty at Niagara, also certainly interplay with all of this. But it’s challenging. Definitely, if I were to choose a court challenge, this would not be the court challenge I would put out there. I would put out a specific court challenge around the jurisdiction in the First Nations land around cannabis. There’s a stronger claim than one around the transportation of cannabis where jurisdiction gets murky.”

Mainville, who has worked with Indigenous communities on the cannabis file for more than four years, says she sees the move by Seven Leaf to sell to Indigenous retailers operating without provincial approval as a sign of some of the failures of the legal system. She says she hopes this is something that will be looked at in the upcoming three-year review of the Cannabis Act.

“Seven Leaf [getting licensed] was definitely seen as sort of a progressive step by an entity to achieve Health Canada licensing as well as Akwesasne licensing. So I think that they were proof that you could do both. Unfortunately, we’re seeing proof otherwise because they’re not really successfully engaging in selling to provincial distributors, which is unfortunate.”

“I think that should be a red flag for Canada that they have to do more for First Nations because this was the Health Canada success story and this is proof that Health Canada has to do a lot more for Indigenous communities.”

Comments are closed.