From The Globe & Mail by Ryan Hook November 30 2023

On Alderville First Nation – a reserve south of Roseneath, Ont. – a dozen cannabis stores make up a short stretch of Highway 45, in what’s been dubbed “The Green Mile.”

Since Canada legalized cannabis in 2018, the sector’s annual GDP sits at about $10.8-billion, sustaining tens of thousands of jobs across the country. While cannabis is federally regulated, the oversight of wholesale distribution and retail is in the hands of provinces and territories.

The dispensaries on The Green Mile mostly fall outside that sector. They’re part of a different market – one that is, surprisingly, not operating under provincial dispensary laws. It’s what Indigenous industry experts call “the red market.”

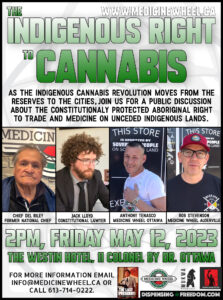

“[Technically] we’re not legal to the Canadian government, and we’re not licensed through the province,” says Robert Stevenson, an Anishinaabe man of the Bear Clan and owner of Medicine Wheel, the first dispensary opened on The Green Mile.

Indigenous people and First Nations across the country are sometimes sidestepping the formal processes for cannabis operations and distributing their own product on the red market instead. Stevenson says it’s a reclamation of land rights laid out in the Canadian Constitution and Article 24 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“The industry has really blossomed over the last six or seven years.”

Health Canada’s expert panel, which was tasked to review the Cannabis Act, has acknowledged red market dispensaries, saying they are “compliant with community-based laws and regulations,” but not federal or provincial laws.

According to the federal government, 47 Indigenous-owned or -affiliated businesses have received a federal licence to cultivate or process cannabis. But only six federally regulated businesses are located within First Nations communities. Meanwhile, more than 475 sovereign Indigenous dispensaries operate across Canada and the United States.

“Health Canada understands that for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis leaders, organizations and individuals, discussions about cannabis legalization and regulation are critically linked to broader issues such as self-determination, reconciliation, and economic and community development,” Tammy Jarbeau, spokesperson for Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada, said in a statement.

“Support for the self-determination of Indigenous peoples is a key objective of the Government of Canada. This must be balanced with the need to ensure that the legal and regulatory framework for cannabis, including criminal prohibitions, is applied consistently across the country.”

While the bulk of Indigenous-owned cannabis operations fall under the “red market” umbrella, others are pursuing the legal route. But that comes with its own challenges.

The Songhees First Nation, located on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, has a unique collaboration with Surrey, B.C.-based Seed and Stone, and it has two state-of-the-art boutique cannabis stores in Victoria. Seed and Stone was started in 2020 by Vikram Sachdeva, an Indian immigrant who, prior to cannabis entrepreneurship, owned a handful of Subway franchises.

“Cannabis needs to have entrepreneurs,” he says.

Sachdeva began pitching Seed and Stone to Songhees Chief Ron Sam in 2021. With this model, Sachdeva says, the Songhees Nation has a majority stake in each store and it has autonomy over the overall direction. Sachdeva, under a separate company called Water Leaf Management, helps manage and run the stores, taking a minority stake.

The Globe and Mail reached out to Songhees First Nation for comment, but it did not receive a response in time for publication.

Risk is the biggest barrier to owning a cannabis store, especially as cannabis companies are facing significant job losses and facility closings, and establishing a licensed cannabis store is a drawn-out process too, full of public hearings, zoning issues and permits.

“It’s not easy to navigate the process,” Sachdeva says. “It takes anywhere from eight to 12 or 14 months.” Legal cannabis stores require government licences, and they compete with government-owned stores, which often sell products for a lower price than privately-owned retailers.

It gets even more difficult when your main competitor restricts the amount of stores you can have. British Columbia, for example, has limited the amount of cannabis dispensaries one company can operate to eight. In April, the provincial government said it will be looking into lifting the cap, but no changes have been announced.

“I hope the province is making it easier, because right now it isn’t,” Sachdeva says. “If the government can open [up to] 39 stores across B.C., First Nations like the Songhees should be able to open as many as they want, too.”

Seed and Stone intends to replicate its model with other First Nations – and Sachdeva says he is currently in talks with three other First Nations on B.C.’s Lower Mainland. But it remains to be seen whether Indigenous-owned cannabis businesses can scale and thrive in the federally licensed market at the same level as ‘red market’ ones.

Stevenson says Medicine Wheel was one of the first dispensaries in Canada to offer edible cannabis products when it opened in 2017. Meanwhile, it took several years for edibles to hit stores in Canada. Since then, the business has expanded operations significantly, opening its own extraction facility, its own manufacturing facility, and its own on-site laboratory. Stevenson says he’s worked in the community to help others open their own cannabis stores.

He estimates half of the residents in Alderville are benefiting from the cannabis industry. “The [Alderville Band council] sees the potential – how much employment and tourism it brings in – and it’s changing lives on the reserve,” he says.

Health Canada says it is responding to the growth of the red market by employing an expert panel to lead a legislative review of the Cannabis Act and focus on how there are “greater barriers” within the legal industry for Indigenous communities.

The panel recently released a report which included a summary of their engagement with Indigenous governments.

A final report will be tabled by the Minister of Health in both Houses of Parliament in March.

Comments are closed.