From RealPeoples.Media EDITORIAL June 18, 2021

SIX NATIONS – On June 9, 2021 elected Chief Mark Hill and the Six Nations of the Grand River Indian Act Elected Band Council passed a new version of their “cannabis law” that will come “into force” on June 21, 2021. The law is a brazen attempt by elected Chief Hill and a small faction of pro-Indian Act band members to claim “sole regulatory and licensing authority over cannabis production and sales” on the territory – in contravention of both Canadian law and the sovereignty and wishes of the Six Nations people.

In order to acquire jurisdiction over cannabis, the Elected Council claims to be “asserting its inherent right to self-determination, which includes the right to freely determine its political status and freely pursue its economic, social and cultural development.” This of course is something that can’t be true, as the Elected Council is wholly the creation of Canada’s Indian Act system, and thus has no “Aboriginal or Treaty Rights” and no right to “self-determine” or “freely pursue” anything.

The new “law” is double the size of the old one, and might better be titled “the Totalitarian Six Nations Cannabis Commission Law” as 32 of its 40 pages detail the vast scope and powers of an unelected and all-powerful Cannabis Commission. The 3-5 member Commission is appointed by the Elected Council and is to be chaired for the next four years by “Chief Commissioner” Nahnda Garlow and will fund itself through fees, fines and seizures levied on the Onkwehon:we cannabis industry.

The Commission will need to collect millions of dollars in revenue in order to cover its costs if the leaked budget summary of the Six Nations Cannabis Commission that the Turtle Island News obtained is correct. According to the Turtle, those documents indicate that expenses budgeted for head commissioner Nahnda Garlow alone totaled $136,800. A further $312,000 was budgeted in costs for other staff, overhead and “membership engagement”, while “the 2020-21 year shows costs of $1,102,700 in consulting fees and $119,900 in production and dispensary development and licensing costs.” The total to date spent by the commission stands at over $3 million, according to the Turtle.

The cannabis regime of a “Six Nations” police state

The level of powers the “law” gives the Cannabis Commission are unprecedented and extreme. The Commission would hold a monopoly on sales of all cannabis products in the territory. Anyone looking to sell any cannabis products in Six Nations would have to buy it from the Commission at prices “inclusive of the Commission’s wholesale margin” (which it may set at whatever price it wants).

The Commission is given the power to send its “Inspectors” – without a warrant – onto the lands and property of any person anywhere on the Six Nations of the Grand River territory (excluding personal dwelling-houses). Their Inspectors are empowered to “remove or seize or copy any record or any other thing that is relevant to the inspection.” Anything so seized – including farm equipment, vehicles, trailers, cannabis, money counting machines, computers, display cabinets, etc. – may be indefinitely held by or outright forfeited to the Commission.

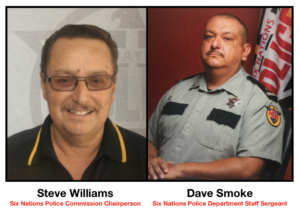

The law puts the Six Nations Police Department (SNPD) under the direct political control of the Commission as their enforcers. The SNPD must seek direction from the commission with respect to “forfeited cannabis”, i.e. the cannabis taken in raids, and “the Commission shall provide written directions to the Six Nations Police, and Six Nations Police shall comply with same.” All SNPD officers are instantly made into cannabis “Inspectors” under the law, and the SNPD must issue a yearly report to the Commission on everything it has done related to cannabis.

The law gives the Commission the power to close people’s businesses, bar them from entry onto their own property, and allows them to impose a cash bond of $10,000 and order the forfeiture of that bond to the Commission. The Commission can also hold its own trials or hearings against anyone who may have broken their law, and may levy unlimited monetary penalties – “a fine in an amount without limit” – if it finds them “liable” for breaking the law.

Appeals of the Commission’s decisions can be made, but only through an arbitrator chosen by the Commission. The person appealing the Commission’s decision has to pay the costs of the arbitrator, as well as the expenses of the Commission if the arbitrator rules in favour of the Commission.

Most ludicrously, the Commission may also issue orders “requiring the liable person, within the period or periods specified in the order, to do or refrain from doing anything specified in the order” for up to two years. This is a very broad and powerful “law” indeed.

The legislation is ultimately a continuation of Canada’s prohibition of cannabis, making it a “criminal prohibition” to possess or distribute more than 30g of dried cannabis, or four cannabis plants.

The lack of any legal definitions in the document is striking, and surely not a coincidence. This means that the definition of what actually constitutes “illicit” vs. “legal” cannabis is unclear – especially in relation to Canadian law. Interestingly, Section 38. (1) (b) of the law indicates that Canadian cannabis that is “legal” according to Canada’s Cannabis Act is considered to be “illicit” cannabis on Six Nations of the Grand River Territory.

An invalid Indian Act by-law, not a “law”

Under Canadian Law, Elected Band Councils operating under the Indian Act have no authority or jurisdiction over cannabis. As Government of Canada spokesperson William Olscamp, (Media Relations for Indigenous Services Canada) stated in an email to Dispensing Freedom, it is the position of the Government of Canada that “there are no specific authorities or definitions in the Indian Act for the regulation of cannabis.”

Band Councils are entities created by Parliament through the Indian Act, and so they can’t re-write or overrule other Parliamentary legislation such as the Criminal Code or the Cannabis Act. That is why the Federal and Provincial governments will only support “harmonized” cannabis regulations on reserve – which means doing everything Canada’s way.

To be legal in Canada’s eyes, all Band Council cannabis rules have to mirror all Provincial and Federal rules and on reserve stores may only sell cannabis from Licensed Producers regulated by Health Canada. Indigenous cannabis products are not viewed as “legal” unless they go through the same regulatory procedures as Canadian LPs. Canada does not accept cannabis products from Indigenous sources or one that are regulated by Indigenous jurisdictions.

So, in reality, the new “Cannabis Law” is really a “draft bylaw,” as it has not been approved by the Minister and likely never will be, since it is not congruent with Canadian law. The law could in fact put its authors and benefactors in a lot of legal hot water, for selling “illicit cannabis” themselves. This is why the law offers the full financial backing of the Elected Council against any legal proceeding or sanction “if such action, suit or other proceeding challenges the validity or enforceability of this Act, its regulations or the right of Six Nations or Council to establish the cannabis regulatory regime contemplated hereunder.”

“Nation Building” by the Six Nations Elected Council

What then explains the rather bold decision of an Indian Act Band Council to put forward a new set of “laws” which are neither congruent with Canada’s laws, nor in accordance with the public opinion, or the culture and customs, the Kayanerenkó:wa (Great Law) and the inherent Onkwehon:we governance structure of the Six Nations?

The answer, it would appear, lies in the intent of the Band Council to somehow turn a colonial administrative office with no treaties and no land rights, into an “Indigenous Nation” run like a police state.

In the fall of 2019 the Elected Band Council underwent what it called a “Realignment Description” and changed its name, color scheme, and logos to match those of the traditional system of the Haudenosaunee.

Through this “realignment” the “Six Nations Elected Council” changed its name to the “Six Nations of Grand River.” Out went the old logo of six figures holding a blood red wampum belt, and in came an all purple logo with the Tree of Peace – a symbol of the Kayenere:kowa – as its centrepiece. The logo contains symbolism relating to the Haldimand Tract and prominently displays the Ayenwatha belt associated with the founding wampum of the Haudenosaunee Five Nations Confederacy.

This appropriation of the emblems of the traditional governance system was not matched by any change in the governance system or political behaviour of the Elected Council. A statement from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy written in 2013 and recirculated in April of 2021, took direct aim at these moves:

“…These elected councils have begun commandeering the distinct symbols, philosophies, and national character of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy – thus misrepresenting themselves to external agencies and limiting the significance of the Haudenosaunee as an original Indigenous system of governance….. The elective systems are foreign entities that are colonizing the culture by misappropriation. Placing our teachings, laws, and symbols within the colonial construct of the elective band council system is morphing decolonization into a meaningless apparition of cultural revitalization and transformation.”

The change in the Band Council’s logo has been matched by a change in political rhetoric, as seen in the Elected Council’s April 26th, 2021 press release. That missive started with a claim “reaffirm[ing] our commitment to “Kayanerenkó:wa” (The Great Law of Peace) which is based on ‘inclusivity, peaceful co-existence and strength, through unity.’” Reference was also made to the “well-known historical and cultural role” that the “Confederacy Chiefs and Clanmothers have in upholding the importance of our languages and culture.”

Missing from this statement is any recognition of the current and actually existing political role of the traditional system, and any mention that the Kayanerenkó:wa is based on the political sovereignty of the people, who all “have their eyebrows at the same height” and who use their clans to make decisions by consensus.

Instead, the Indian Act Band Council continues to usurp the traditional system as it appropriates the symbols and language but not the content of the hereditary system of governance. In doing so it completely ignores what the people of Grand River themselves want.

What do the people want?

In the largest survey of its kind, conducted in December of 2017, over 731 Six Nations members answered 11 questions about their views on cannabis in the territory. The results indicated that only 3.1% of respondents thought that the Six Nations Elected Council should have a say in regulating cannabis while only 4.4% wanted the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Chiefs Council to regulate it. Canada was least of all, as only 1.6% of respondents wanted the Province of Ontario and the Government of Canada to be involved in regulating Six Nations cannabis.

The clear majority of respondents – 53.6% – held that cannabis consumption should be “regulated” by traditional medicine people and according to Haudenosaunee custom. This perspective is similar to the approach taken in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, where customary law and practices regulate the cannabis industry and where principles of clan governance in relation to cannabis have been articulated.

The next largest group of respondents – 28.2% – thought that the industry should be regulated by an association of Indigenous cannabis retailers. And a comparatively large number of people – 21.8% – weren’t sure how cannabis should be regulated, or if it should even be regulated at all.

The Onkwehon:we people growing and selling cannabis on their own lands have every right to support themselves and grow this industry free of any interference from the Indian Act Band Council or whatever fraudulent “First Nation” it tries to turn itself into.

But unlike in many other Indigenous jurisdictions – such as Kanehsatake, Pikwakangan, Alderville, Tyendinaga, and Oneida – the cannabis shops in Six Nations of the Grand River have not been left alone. The Six Nations Police Department has engaged in the heaviest anti-cannabis policing regimes of any First Nation in Ontario, and it has raided over a dozen sovereign cannabis dispensaries in the last several years. The charges however, have rarely stuck in court, and the heavy handed violence used by the police has sparked significant community backlash.

Elected Chief Mark Hill and the rest of the Elected Council, Cannabis Commission Chair Nahnda Garlow and the Six Nations Police Department have presented to the world through this cannabis law their intent to utilize cannabis as a resource to finance a neo-colonial police state at Six Nations.

Out with the traitors, long live the Great Law!

Comments are closed.