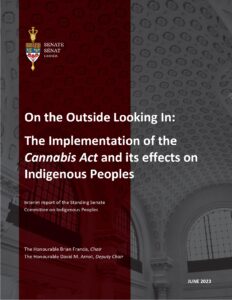

Some Indigenous leaders see the upcoming three-year review of federal pot laws as a chance for a new deal

From CBC.ca by Erik White February 26, 2021

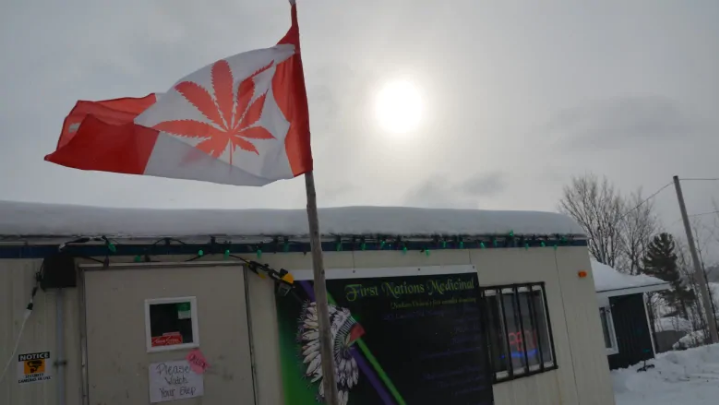

Three years ago, before the federal government legalized cannabis, you could buy it on many First Nations in Ontario.

In some cases, these pot shops were totally legal, opened with the permission of their chief and council.

In many other communities, these dispensaries operated in a legal grey area.

That has now gone on for years and there is a growing push to set laws surrounding the sale of cannabis on reserves, especially as dozens of provincially-regulated stores are opening and eating into the market.

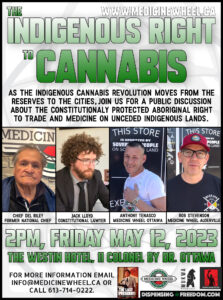

Rob Stevenson remembers being “very nervous” when he opened Medicine Wheel Natural Healing in Alderville First Nation near Peterborough in 2017 in the “very unclear landscape” before cannabis was legalized by Canada.

But he says he checked with the First Nation and local police and got “tacit blessing” to start selling cannabis.

Now there are many cannabis dispensaries in the small community of 300 along what’s become known as “the Green Mile.”

Stevenson says Alderville is working on a cannabis law, which he thinks is a better model than signing up for the provincial regulatory regime, which comes with “tight margins” and high licensing costs.

“Now for a First Nation to follow that government model, they’re at a huge disadvantage,” he says.

“Why are people going to take that time to drive out to a reserve for the exact same price for the exact same protect?”

Stevenson says instead of being dismissed as “black market,” it’s time for Indigenous retailers to carve out a “red market” in the cannabis industry that’s unique from what’s offered at provincially-regulated pot shops.

“I believe the cannabis industry can make us independent,” says Mike Davis, the owner of the Green Cross dispensary in Six Nations of the Grand River.

His and the other shops in his community also opened without permission of the First Nation, which has since created its own cannabis commission for regulating the industry.

Meanwhile, Davis and the other dispensaries have formed the Six Nations People’s Cannabis Coalition, which is setting it’s own standards for quality testing and asking for ID.

“It’s kind of how the cigarette industry is down here. All these smoke shops down here are technically illegal because there’s no taxes being paid on those,” says Davis.

“That’s how people make their livelihood, that’s how they put bread on the table on my reserve.”

Wahnapitae First Nation north of Sudbury is set to hold a referendum on cannabis sales Feb. 27, the second time it’s been put to a vote because there wasn’t enough turnout the first time to make it binding.

The First Nation is asking its citizens for permission to pass a cannabis law, allowing chief and council to decide who gets a license, what sort of fees they pay to the First Nation, what kind of product standards need to followed and where the shops are allowed to be located.

There have been two cannabis dispensaries operating in the community of 100 for the past three years. Both opened without government approvals and have been raided by police several times, but allowed to re-open each time.

Derek Roque started Creator’s Choice in Wahnapitae and is facing three Cannabis Act charges that are slowly making their way through court.

He says he has since been pushed out of the business by his former partners, but is now working as a consultant for First Nations cannabis dispensaries being planned across the province.

Roque says he won’t be voting in the referendum he calls a “complete joke” and believes having a cannabis law goes against his people’s traditions.

“It has been sold in a good way. And that is the way of the Anishinaabe people,” he says.

Isadore Day is a former Ontario regional chief who now runs a consulting firm called Bimaadzwin, that has helped many First Nations communities with their cannabis policy.

He believes the best path for First Nations is to sign on to the provincial regulatory system, especially when it comes to product standards to assure the consumer that what they buy on a reserve is safe.

But then Day believes it’s also important for chiefs and councils to pass their own laws governing cannabis in their own territories.

“Right now, it’s one thing for us to push forward our laws and we don’t need other governments to recognize us, but if we want to access the mainstream economy, we’re going to have to find a way to harmonize our efforts,” he says.

“The next year or so will be about getting those proposed amendments in place that recognize our laws, not dictate to us.”

Day says the federal cannabis laws will come up for a three-year review this fall, giving First Nations an opportunity to make a new deal with the Canadian government.

Comments are closed.