By Leslie Logan

Complex community divisions surface; opportunity for community-based, community-designed regulatory system develops

The Mohawks of Akwesasne have never shied away from economic opportunity, even if it involved risk. When the Canadian government legalized medical cannabis and then moved towards legalizing recreational marijuana across its ten provinces and three territories, the people of Akwesasne saw a chance to engage in a budding industry with tremendous economic potential.

Medical marijuana became legal in Canada in 2001, and on October 17, 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivered on his promise to legalize recreational pot. With explosive revenue projections, business-minded Akwesasronon, and other Canadian First Nations communities began contemplating ground-floor entry into the cannabis market. Analysts with the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce have forecasted the cannabis industry to be worth $6.8 billion annually by next year.

With national decriminalization of marijuana, and the prospect of windfall revenues, who wouldn’t want a piece of that action?

As the legalization date approached, many Canadians waited with baited breath, gripped by an incomparable sense of glee and anticipation akin to what a five-year-old experiences upon the arrival of Santa Claus. Others, particularly those in law enforcement and provincial governments, eyed the date with a growing sense of dread, feeling ill-prepared and poorly equipped to deal with the many unknowns attached to an industry in its infancy.

Critics have called the legalization of recreational marijuana in Canada a national experiment that has the potential to alter the country’s social, cultural, and economic fabric. First Nations people on the ground in reserves across the country, witness to a history of substance vulnerabilities, questioned the onslaught of legal marijuana in their communities and what might unfold. But while there were apprehensions, there was also excitement about the transformative power that cannabis promised as an economic change agent.

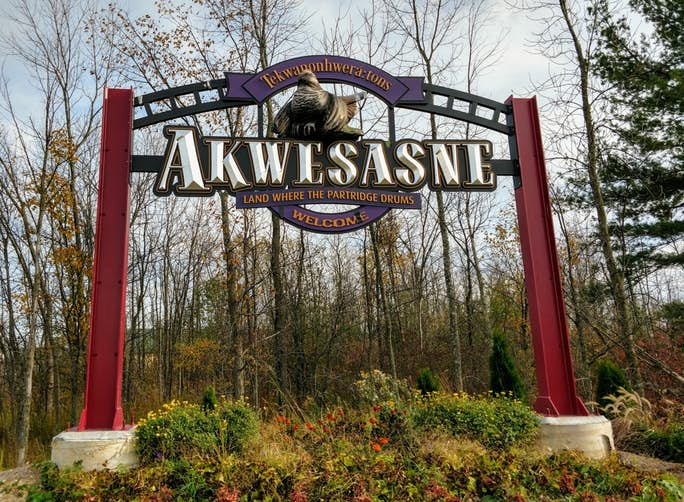

Enter Akwesasne

To say the situation at Akwesasne is complicated is like saying the sun burns hot in Phoenix in July. Penn State anthropologist Dean Snow, in his 1996 book on the Iroquois, described Akwesasne as a community marked by “unusually complex political factionalism.”

An article in Politico in July 2018 underscored the complicated nature of this Mohawk community calling it a jurisdictional nightmare, stating: “Akwesasne is a town and a nation, and it may be the most geopolitically absurd place in North America.”

Akwesasne is a Mohawk territory spread over an area of about 40 square miles that is struck through by the US-Canada international border, sitting in both countries; it straddles two provinces: Ontario and Quebec; is couched by the St. Lawrence River and bisected by the “seaway corridor,” and sits in New York state.

There are now at least ten entities that attempt to assert some semblance of jurisdiction in and over Akwesasne including the United States, Canada, New York state, the provinces of Ontario and Canada, the Canadian recognized elected band council: the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, the U.S. federally recognized elected government: the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, the traditional longhouse councils: the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs, the Kanienkehaka longhouse — commonly referred to as the Warrior longhouse, and the recent derivation, the Indian Way Longhouse. (In the Mohawk language, Kanienkehaka is the word for the Mohawk people, which translates to “the people of the flint.”)

Along with those governing bodies and traditional councils, there are the New York, Ontario, and Quebec law enforcement agencies, the Akwesasne Mohawk Police Service in St. Regis, Ontario, the St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Police in New York, and the U.S. and Canadian customs and border authorities.

Cannabis sprouts seeds of dissension

It is no small wonder then, that given the geographics, borders, layers of governments, conflicting authorities and jurisdictional issues, politics, and conflicting ideologies — that problems would develop at Akwesasne around cannabis.

On two separate occasions in February, the Akwesasne Mohawk Police, accompanied by the Ontario Provincial Police and officers from the Ottawa city police force, conducted “raids” on two cannabis dispensaries in Akwesasne on Kawehno:ke, (Cornwall Island, Ontario). The dispensaries, AK420 and Wildflower, are not licensed retailers; not by either Ontario or the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, which has developed interim cannabis regulations.

Wildflower is a business collective, established and licensed by the Indian Way Longhouse, a newly created entity given life under the leadership of Roger Jock, who was previously on the Men’s Council of the Warrior Longhouse.

It was after the second sweep of the two dispensaries on Kawehno:ke, on February 22, that protesters gathered on Cornwall Island. Later that evening, some 100 protesters assembled at the Akwesasne Mohawk Police Service headquarters in Kana:takon, (St. Regis, Quebec).

As the crowd grew, St. Regis Road, leading into Kana:takon, was blocked by tribal police, including the ice road. The deep freeze of that bitter Friday night didn’t help keep heads cool; as the night progressed, in the dark, wee hours of Saturday morning, tempers flared and all hell broke out.

Akwesasne Mohawk Police reports indicate that at approximately 2 a.m., several members of the protest group confronted officers on the scene. A struggle ensued and two officers were injured, requiring medical attention. Other protesters smashed the windshield of a police cruiser, and another police SUV was stolen, driven out on the ice of the St. Regis River and set afire.

A burning police vehicle in Akwesasne. (Video used with permission: Submitted by Marlon Johnson)

Earlier in the evening, three women, representatives of the clans of the Indian Way Longhouse met with members of the police force, expressing dissatisfaction with the raids and opposition to the non-Native members serving on the force, calling specifically for the resignation of Shawn Dulude, the non-Native chief of police. When those talks went nowhere and the three clan representatives left, fury and fire erupted.

The Indian Way Longhouse issued a statement to the press the next day calling the incident “a day of outrage” (against the raids) and against “that agency’s rejection of the 3-clan system.”

Although the raids sparked the protests, the refrain that has been heard ringing throughout Akwesasne, over the airwaves, and on the streets, and seen on Facebook posts, is that the turmoil that erupted is about more than just cannabis.

Charles “Chaz” Kader, a spokesman for the Indian Way Longhouse, summed up the sentiment saying, “There are a number of irritants.” Kader shared a list of simmering issues that go beyond cannabis, the raids, and the licensing authority of Mohawk Council that have exacerbated current tensions. Kader said, “There is frustration with the recent Dundee land settlement agreement, the non-Native presence on the police force, the perceived selective nature of the raids, and the desire for jobs and economic opportunities.” Kader said that at a recent tribal council meeting community members also raised the issue of the 1990 unsolved murders that occurred when Akwesasne was embroiled in a civil war over casino gambling.

Social media posts support the notion that the dissatisfaction goes deeper.

Fallan Davis Jacobs and Josh Jacobs, owners of AK420, posted video recordings of the first raid on the dispensary’s Facebook page. AK420 is not licensed, and the two recorded the exchange with the Akwesasne Mohawk Police and other officers that were onsite. Josh Jacobs can be heard saying: “This is Indian land. Provincial law doesn’t apply here.” In the video, Jacobs tells the officers that they don’t have jurisdiction.

Fallan Jacobs follows suit in a separate recording asking: “What law are you following? Whose law is this?” On her Facebook page, Jacobs states that MCA is a government that represents assimilation. Her page acknowledges the need for law and order, but she asks, “Under whose law does this order come from?” She maintains that her ability to operate the dispensary falls under the authority of the Two Row Wampum.

The Two Row Wampum is a living treaty that was made to establish relations between the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse) people and the Dutch in the early 1600s. It provides that each nation will respect the ways of the other. The Haudenosaunee describe the treaty belt in this way: “In one row is a ship with our White Brothers’ ways; in the other a canoe with our ways. Each will travel down the river of life side by side. Neither will attempt to steer the other’s vessel.”

Meanwhile, the Mohawk Council of Chiefs issued their own response to the AK420 declaration that its authority falls under the Great Law. “We have learned through recent media reports that the cannabis dispensaries… in operation on (Cornwall Island) have misled people by making the claim that they are operating legally under the strength of the Kaianerakowa (Great Law of Peace),” Mohawk Nation Longhouse administrator Bute Hill wrote in a statement. “It is our position that without our approval, these individuals cease any further claims that they are conducting any business under such laws and agreements that remain sacred to us.”

Jacobs and others have withdrawn their membership from either the rolls of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe or the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, and do not consider themselves citizens of the United States or Canada. Many followers of the Warrior longhouse and the Indian Way Longhouse do not recognize the authority of the band council, the federally recognized St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, New York State, or the US or Canadian federal governments, or any of their concomitant law enforcement agencies.

Yet questions of legitimacy run both ways at Akwesasne. Indian Time, the newspaper and record of note, reported that it had spoken to community members, especially elders, and that some had questioned the validity of the Indian Way Longhouse and the violence that its followers had perpetrated — which the paper noted, is in direct contrast to the ideals of the Great Law, the guiding principles of peace of the Haudenosaunee.

The new splinter in the Warrior longhouse suggests a fresh rupture among followers. When asked about the reason for the break from the Warrior longhouse and the creation of the new Indian Way Longhouse, Kader summed it up by saying, “There are distinct viewpoints within the three longhouses. Sometimes you want to be with people you agree with, rather than those you disagree with.”

The splinters within groups at Akwesasne reflect the many differing perspectives among Akwesasronon. Regardless of one’s view, political position, spiritual leanings or allegiances, the people at Akwesasne have learned to coexist, even if it is sometimes an uneasy coexistence.

History of resistance

Akwesasne has a formidable history and strong tradition of political activism, nationalism, and resistance, having adopted its own Warrior Society branch in the 70s, following its creation at Kahnawake, near Montreal. The Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs at Kahnawake established the Warrior Society as a measure of national defense, territorial security, and community protection. The commonly accepted translation for the Rotisken’rakehte (warriors) in the Mohawk language is: “men who take on the responsibility to protect and defend their people and territory.” The development of the Warrior flag has become synonymous with the assertion of indigenous rights and sovereignty.

Yet despite its initial Mohawk protections, the Warrior Society has also turned their ideology inward to challenge the governing entities within their own communities, sowing divisions squarely against their own people. The Warrior Society was central to the bitter internal conflict in 1990 — Akwesasne’s civil war, when members armed themselves with AK47s, and a firefight resulted in two deaths. Akwesasne was riddled with roadblocks, marred by gunfire, torn apart by blood feuds, and fractured by rival factions that pitted Mohawks against Mohawks in a struggle for power. In the same year, members of the Warrior Society took up with the Mohawks of Kanesatake, west of Montreal, to protest the development of a golf course over burial grounds, which became known as the Oka Crisis. That summer-long conflict resulted in two fatalities; a Mohawk elder and a Quebec constable, and nearly a hundred were wounded.

The Warrior Society at Akwesasne has developed a reputation for being militant, strongly opposed to any external government authority or imposition of outside laws. “The right to a free and independent existence” is the axiom that embodies the Warrior ideology. On their face, the ideals of the society are not abrasive, but in practice, over time, the high-minded principles have become perverted; with Warrior activity and proclamations increasingly perceived as extremist, lawless inclinations.

Cannabis as a Catalyst

With the advent of the new cannabis market, the rejection of outside law and the calls for Kanienkehaka authority have been given renewed strength through the Warrior longhouse, and its recent Indian Way spin-off..

According to Kader, the protesters who gathered at the Akwesasne Mohawk Police Services headquarters were riled by the dispensary raids, but he said many harbor deep-seated grievances that, at their marrow, have to do with opposition to the power base of decision makers, the influence of outside authority, and frustration at being left out of the conversation.

“There is a new surge, a young generation that self identifies as ‘progressive traditionals’ that want better economic opportunities,” said Kader. He said the younger people are expressing concern about the future, but that all of the followers of the Indian Way Longhouse want a place at the table. “They want a voice; they don’t want to be discounted and they want to be included in how the future develops.” And the economic future it seems, involves cannabis.

The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne conducted a community survey seeking feedback on whether the community was in favor of establishing cannabis businesses for economic development and whether the community was in favor of the council establishing regulations. However, council officials developed interim regulations with very little direct community engagement or meaningful input.

The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne passed the Akwesasne Interim Cannabis Regulation (MCR 2018 #212), which governs the possession, use, cultivation, sale, and distribution of cannabis in Akwesasne. The regulation, adopted in October when Canada legalized recreational pot, requires cannabis-related businesses to obtain a license from the Council.

The interim regulations declared that the unlicensed commercial production, distribution, possession or sale of cannabis would be prohibited in Akwesasne. The regulations were posted and publicized, informing the community that the provisions would be enforced, with violations leading to prosecution under applicable legislation. To date, the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne has not issued any licenses.

Calls for peace and unity

After the clash over the raids, the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, in conjunction with the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, issued a statement calling for peace. The two bodies acknowledged the people’s right to peacefully demonstrate but stated they did not condone aggressive behavior or acts of vandalism. Officials asked all Akwesasronon to “embrace ska’nikónri:io and use good minds to come together in dialogue.”

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne Grand Chief Abram Benedict appeared on Akwesasne TV following the flare-up. Benedict acknowledged that mistakes had been made, but that lessons had been learned.

“I realize that there wasn’t a whole lot of dialogue before this. We should have been conversing with other interested groups, bodies, stakeholders, and representatives,” said Benedict. He has since committed to a constructive dialogue, to finding commonalities among all parties, and has committed to finding community-based solutions.

The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne has committed to the development of a fulsome Akwesasne Cannabis Law enactment process. Mohawk leaders want to ensure that any licensed operations in Akwesasne have access to a safe, credible supplier of cannabis and a system of checks and balances that is representative of the community.

“We need to come together, we want to make sure that we’re reaching out to people, we want to make sure that people are heard,” said Benedict. “We don’t want to alienate one people over another.”

In the intervening days, there have been a number of meetings between all parties. There have been People’s Fire meetings, Indian Way Longhouse organizational meetings, and meetings with Benedict and other Mohawk leaders. “The lines of communication are open,” said Benedict.

The Indian Way Longhouse has developed their own set of proposed cannabis regulations. Kader says that its supporters agree about the need for regulations and that they want input into the development of a mutually agreed upon regulatory system.

Lack of consultation breeds lack of consultation

The Cannabis Act requires growers to obtain licenses at the federal level; while retail licenses are left to the provinces—and provinces have the liberty to determine the manner of sales, resulting in a lack of uniformity across the country. The act is silent on regulatory requirements or guidance for First Nations participation in the industry.

The federal government was criticized for failing to include Indigenous communities in the process that led up to the enactment of the cannabis law.

In May 2018, the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples released a report citing “an alarming lack of consultation” in the development of regulations.

The report stated: “Indigenous peoples have the inherent right of self-determination, including the appropriate law-making authority to make meaningful decisions that affect the lives of their people and communities, including regulating cannabis.”

Former Assembly of First Nations regional chief for Alberta, Cameron Alexis, complained that the federal government failed to consult with First Nations leaders. In a prescient statement to the CBC, Alexis asked, “So whose law is going to apply?”

Given the dearth of meaningful consultation with Native communities, the lack of language in the Cannabis Act that pertains to First Nations, and the differing retail approaches province by province; combined with unfettered enthusiasm by Native entrepreneurs to open on-reserve dispensaries, the prospect for First Nations’ participation in cannabis development was practically a guaranteed landmine.

What’s past is prologue

In the days following the incident at Kana:takon, Indian Time ran a headline that harkened back to the ravages of 1990. The article reported that many elders were shaken and worried, as the recent struggle and the torched police SUV was reminiscent of the strife and destruction that occurred nearly 30 years ago.

Grand Chief Benedict acknowledged those concerns, “We don’t want a recurrence of what happened then. We have seen the dissension, pain, and hurt that was caused by past conflicts; we don’t want that again,” he said.

Recreational cannabis was legalized in Canada just under five months ago. It has presented Akwesasne with both opportunity and disruption. There is optimism and hope that the flashpoint in Kana:takon will serve as an opportunity for all parties and perspectives to coalesce.

“It’s about us coming together as a community, finding commonalities and coming up with solutions. The threats to us as a Nation are not internal; they are external,” said Benedict. “Our strategy going forward has to focus on the collective.”

He recognized that there will continue to be issues and challenges, but remarked upon the strengths of the community and its ability to build a system of its own. “At the end of the day, we want a system that our people can agree upon and approve. And ultimately, we want prosperity for our people.”

Darren Bonaparte, an Akwesasne Mohawk, is the author of the Wampum Chronicles, a series of online essays on the history of the Mohawks at Akwesasne. In his introduction, he wrote: “It is my hope that history will serve as a reminder to Mohawks today that our grandfathers survived far worse political crises than we will ever know. We owe it to future generations to learn from those that have come before us.”

Comments are closed.