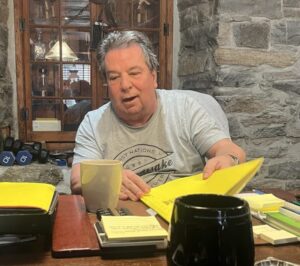

Matthew Esquimaux, the owner of Buddies Smoke Shop in Aundeck Omni Kaning, shares his story of ongoing police persecution.

AUNDECK ONNI KANIG – Ten years ago, a judge told Matt Esquimaux, “You are a career pot seller, that is all you do, you don’t do anything other than sell weed.” At the time Esquimaux did not realize how prophetic those words would be.

Esquimaux, an Ojibway father of five young girls, lives in Aundeck Omni Kaning First Nation (AOK) and is currently facing Cannabis Act charges after his store was raided by UCCM Tribal Police on September 16th, 2019 – in clear violation of the terms of a referendum held by the people of AOK mere months earlier.

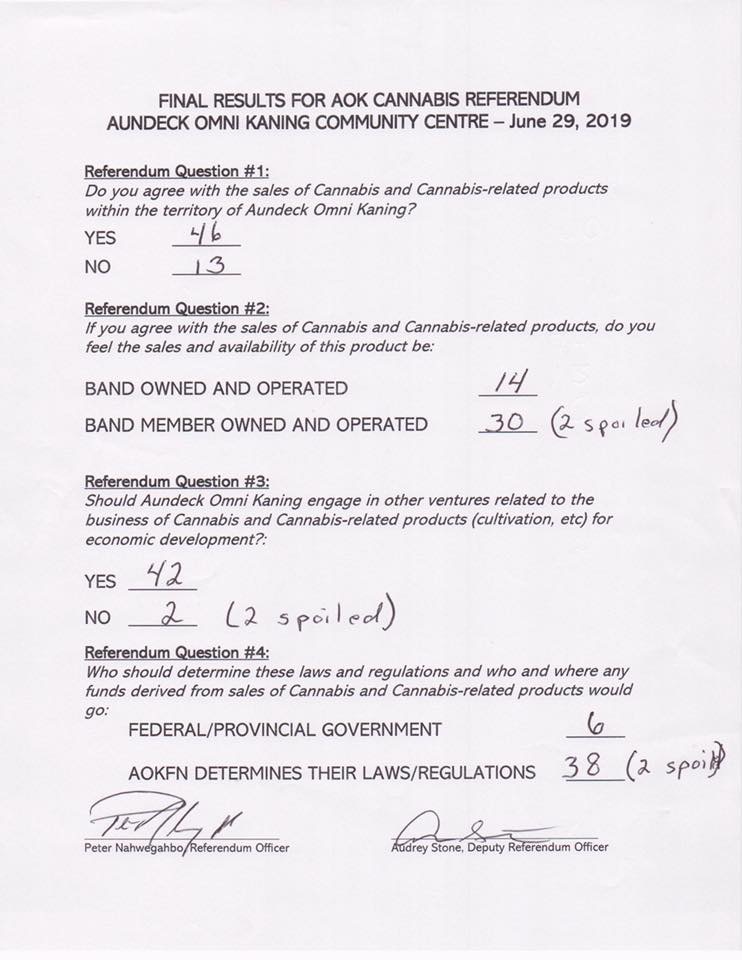

The referendum, which was held in June of 2019 and organized by the Band Council, delivered clear pro-cannabis results. 78% of residents supported the sale of cannabis within the community. 68% said the industry should be run by individual band members such as Esquimaux rather than by the community having band-owned stores. A full 95% said that AOK should engage in other aspects of the Cannabis industry besides retail such as cultivation and processing.

The final question on the ballot was “who should determine these laws and regulations and who and where any funds derived from sales of cannabis and cannabis-related products would go?” With the options of choosing AOK or the Federal government, 82% of respondents said AOK should make their own laws; a clear endorsement of Indigenous sovereignty.

Policing in violation of First Nations laws

When the UCCM Police raided Buddies Smoke Shop – Esquimaux’s store – several months later, they were acting in violation of their own policies concerning the delegation of policing authority. The UCCM Police receive their authority through a policing agreement made with the United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising that is to occur “in a manner consistent with the First Nation laws.”

Consequently UCCM Police must take into account First Nation laws – including those made by referendum – when exerting their authority. In raiding Esquimaux’s store, the UCCM is on the wrong side of the law, because Mr. Esquimaux has done nothing wrong in running his medicinal cannabis dispensary in accordance with the decisions of his people to authorize cannabis sales in their territory.

Buddies Smoke Shop is treated like any other business on reserve by Chief and Council. During the Covid-19 pandemic Esquimaux received $2000 from his Chief in Council – the same amount given to other reserve businesses as compensation for economic losses during the pandemic.

The UCCM also patrols Sheguiandah First Nation where five cannabis stores operate openly following an internal decision making process in the community to regulate its own cannabis industry. The UCCM has indicated that it respects the First Nation’s decision, and there have been no raids of cannabis stores in Sheguiandah.

Persecuted for a love of cannabis

When the UCCM police raided Esquimaux, they brought a battering ram to his front door even though they knew the dispensary was in an outbuilding behind Esquimaux’s house. The cops were about to smash in the front door when Esquimaux’s 14-year-old daughter answered the door. The court disclosure states that the police then served his daughter with a warrant and began searching the premises.

The police searched the entire house before moving on to the dispensary, a large garden shed in the backyard, separate from the house, with its own driveway and parking. Then, according to Esquilmalt, the cops ”went and got my guy, handcuffed him, and brought him through the house, handcuffed in front of my kids and then put him in the cruiser just to drive back to the dispensary.”

This is far from Esquimaux’s first brush with the law – he has been persecuted for selling cannabis his entire adult life. Despite being arrested for possession of cannabis many times, Esquimaux kept selling the plant until he was arrested by UCCM tribal police and given a 2-year prison sentence for trafficking the plant.

The cops apprehended Esquimaux when he was attending his grandfather’s funeral and was seized by 8 UCCM tribal police who knew he that had outstanding cannabis related warrants in Ottawa. They then drove him to North Bay before calling the Ottawa Police about his warrant. According to Esquimaux, “They wanted to know the radius of the warrant, they were told 500km, they asked how far away they were in North Bay, it was 498km so they told the Ottawa Police to come and get me.”

Going to jail for 2 years as a result of these charges deeply affected Esquimaux. “My girlfriend of 10 years committed suicide while I was in jail because she didn’t believe that I would make it out…. I did two years in prison, lost 2 years of my kid’s life and then I quit, didn’t even smoke cannabis for 10 years.” Speaking of his interactions with UCCM, Esquilmalt says, “they’ve really destroyed my life.”

After getting out of jail 10 years ago, Esquimaux committed to quitting marijuana and started going to work as a cook, one of his other major passions. He ran a successful catering company serving indigenous communities across Manitoulin Island. However, while running the catering company Esquimaux began to experience severe back pain. Doctors could not determine how he injured his back aside from the fact that Esquimaux went from 300lbs to 200lbs very quickly. Faced with the prospect of surgery, he decided to try CBD. The CBD relieved the pain almost immediately, and Esquimaux realized that he might be able to avoid surgery with it.

Realizing the benefits of medicinal cannabis, Esquimaux decided to re-enter the cannabis industry as Canada moved towards legalization. “Creator pushed me towards this by giving me my sore back, and sent me back to doing what I am supposed to be doing, selling weed” says Esquimaux. A driven entrepreneur, Esquimaux plunged back into the industry with “what little money I had left.”

“Wellness check” ends in hospitalization

However, since opening his dispensary, Esquimaux has faced an un-ending string of harassment from the UCCM Police. In addition to the raid and harassment from having attend a house party, Esquimaux described an incident where a friend left his house driving a dirtbike borrowed from another friend. After running out of gas, the police approached his friend and had a problem with the plate not matching the description of the bike. Finding out that this person had just left Esquimaux’s residence, they went to his house and threatened Esquimaux with a ticket. “How can you charge me with anything when it’s not my bike and I wasn’t riding it?” asked Esquimaux.

Most recently, in July of 2020, the UCCM arrived at Esquimaux house to perform a “wellness check” on him and his children. As he loudly told the officers to leave and get off his property, officer J. Panamick, who did not observe social distancing and who was not wearing a mask, claimed Esquimaux “assaulted” him because spit landed on him as Esquimaux was demanding that leave.

The interaction was filmed by Esquimaux, until he was arrested in front of his children. During the arrest, police injured Esquimaux’s back, charged him with assault, and sent him to the hospital.

As a result of this constant harassment by police, Esquimaux has spent much of the last 10 years on bail conditions awaiting a trial, only to see his charges get thrown out. With his most recent experiences, Esquimaux feels comfortable representing himself due to his years of experience with the Canadian justice system. Despite his efforts to bring the matter of the cannabis raid on his shop to a speedy trial, the Crown has been dragging its heels, and one year later the case still hasn’t gone to pretrial.

Esquimaux feels confident in his abilities in court. “I have all five of my kids for a reason,” he notes, after having successfully battled CAS in court for custody of them. However because of the police escalation of harassment, Esquimaux is currently reaching out to lawyers specializing in suing the police for misconduct, and looking to build a coalition of others who want an end to colonial policing on Indigenous lands.

Be First to Comment