Two major conferences held in Treaty 7 and Treaty 6 territory in November of 2018 focused on how Indigenous people could take advantage of new opportunities around cannabis and hemp following the recent Canadian legalization of the plant.

These well attended conferences were a clear sign that Indigenous entrepreneurs and political leaderships from many different nations are choosing to get involved in the cannabis industry in the post-legalization era.

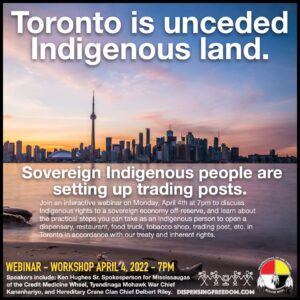

The crucial issue discussed at both conferences concerned how best Indigenous people could be involved in this industry on their own terms, without being subordinated to the Canadian government or the multinational corporations which have swiftly come to dominate Canada’ legal cannabis markets.

The first conference, the National Indigenous Cannabis and Hemp Conference, saw over 500 delegates gather between November 18-21, at the Grey Eagle Resort and Casino in Tsuut’ina Nation in Calgary, Alberta on Treaty 7 Territory.

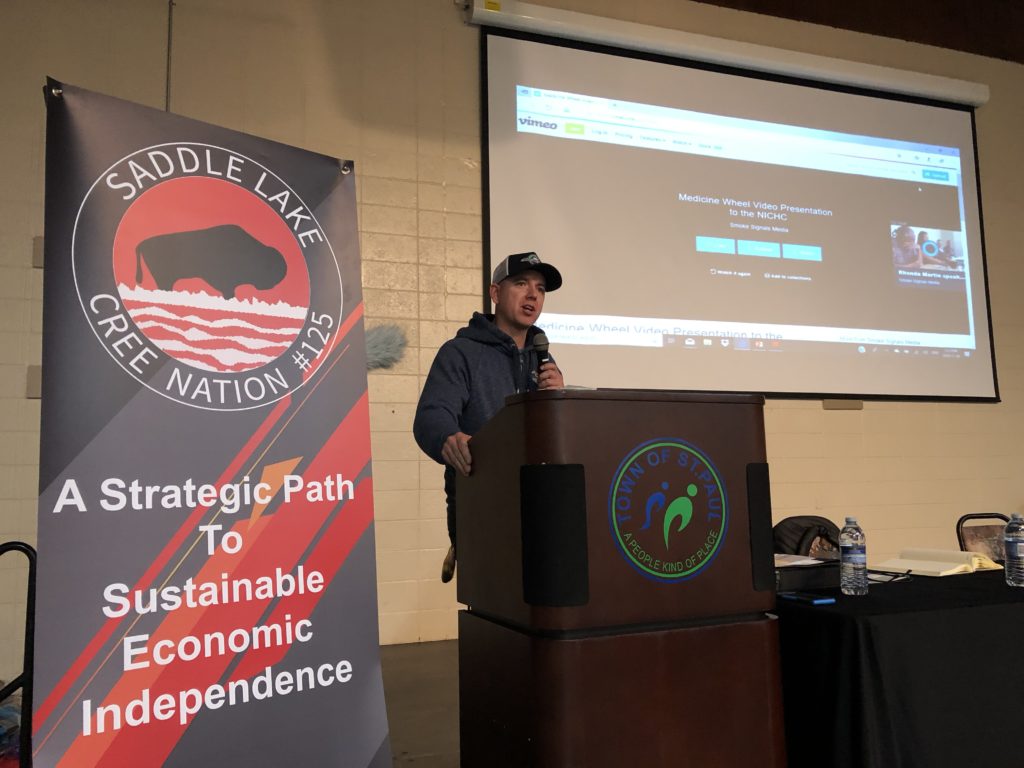

The second conference, titled “A Strategic Path to Sustainable Economic Independence,” was hosted by the Saddle Creek Cree Nation the following week, November 26-27, at a community centre in Saint Paul’s, a two hour drive west of Edmonton, on Treaty 6 Territory. While both conferences featured extensive representation from First Nations leaderships, entrepreneurs and industry players, each conference had its own distinct character and flavour.

National Indigenous Cannabis and Hemp Conference

The NICHC conference had the look and feel of a glitzy high-level corporate business conference. The event was hosted by the Tsuu’tina Nation, an economically powerful First Nation on the southwestern border of the Calgary city limits. The gathering was held in the state-of-the-art conference centre attached to the Grey Eagle Casino and the event was smoothly and effectively organized to the highest standards.

The leadership of the Tsuut’ina Nation is strongly grounded in its treaty rights and traditional leadership systems. As conference convenor Isadore Day, the former AFN Regional Chief in Ontario put it, “it’s no accident that the conference is happening where it is.” During their speeches, Tsuu’tina leaders such as Xakiji Chief Lee Crowchild and Councillor Regena Crowchild explicitly pointed out that their nation’s sovereignty and freedom trumped Canada’s regulatory framework on cannabis, and encouraged conference participants to act within their treaty rights to do what is in the best interests of their own people.

Regena Crowchild, a long-time Tuus’tina leader, gave one of the most memorable speeches at the conference, and summed up the thinking of many on the question of indigenous cannabis and Canada. “When you deal with cannabis, like gaming and other areas, it’s all about our relationship with Canada. Canada is a state, and Canada is in our territories as a result of our treaties… Their laws and general application do not apply here because we have Treaty. It’s time the Indigenous people start asserting their jurisdiction. Why do we need the Federal government to give us approval? Why do we need a license? We should be issuing our own licenses because that’s within our jurisdiction.”

Regena Crowchild’s speech was repeatedly met with applause as delegates agreed with her perspective that the real issue at stake is sovereignty, not cannabis, and that Indigenous nations must act on the basis of their rights to self-determination. Chief Lee Crowchild indicated that the Tsuu’tina nation has been moving forward precisely on this basis. Before Canada’s legalization of cannabis, the Tsuu’tina held a referendum to assess their people’s interest in the cannabis industry, and with the clear support of their people, they enacted their own cannabis law which came into place on October 17th, 2018. The chief of police of the Tsuu’tina nation indicated that the cannabis business operations of their nation would be protected from raids or outside interference because of this framework.

Chief Lee Crowchild also drew attention to the dangers that commercialization could bring in this new green economy. “Elders have long talked about cannabis being the medicine that will help. We must maintain our symbiotic relationship to this medicinal plant and all other Indigenous medicines. There has to be balance as we move forward. If the only driver is economic development then it becomes the drug of addiction and the people will be foreign to the help that this medicine provides. We must move forward with our fundamental beliefs in mind so our peoples and others will benefit from the healing aspects of this medicinal plant.”

A veritable who’s who of the Indigenous cannabis industry

One thing that is clear from a quick scan of the NICHC program is that this was a conference full of movers and shakers from across the national Indigenous scene who were making bold strides forward in the emerging cannabis industry. Costing close to $1000 to attend, the NICHC conference was organized in such a way as to facilitate involvement of pro-cannabis First Nations leadership and participation in the cannabis industry from First Nations leaderships.

Howard Silver, the original conference convenor, became seriously ill and was unfortunately unable to attend the conference. His duties were taken over by former Ontario Regional Chief Isadore Day, who was one of the key organizers of the conference. Day was also a co-chair of the “Cannabis Task Force” that was created by the Assembly of First Nations to respond to Canadian cann-abis legislation.

This task force was highly critical of the failure of all levels of the Canadian government to consult with Indigenous people about cannabis legalization, and while Canada did little to address the concerns of Indigenous people regarding cannabis, the NICHC conference appeared to be one outcome of earlier efforts between First Nations seeking to understand how to respond to cannabis legalization.

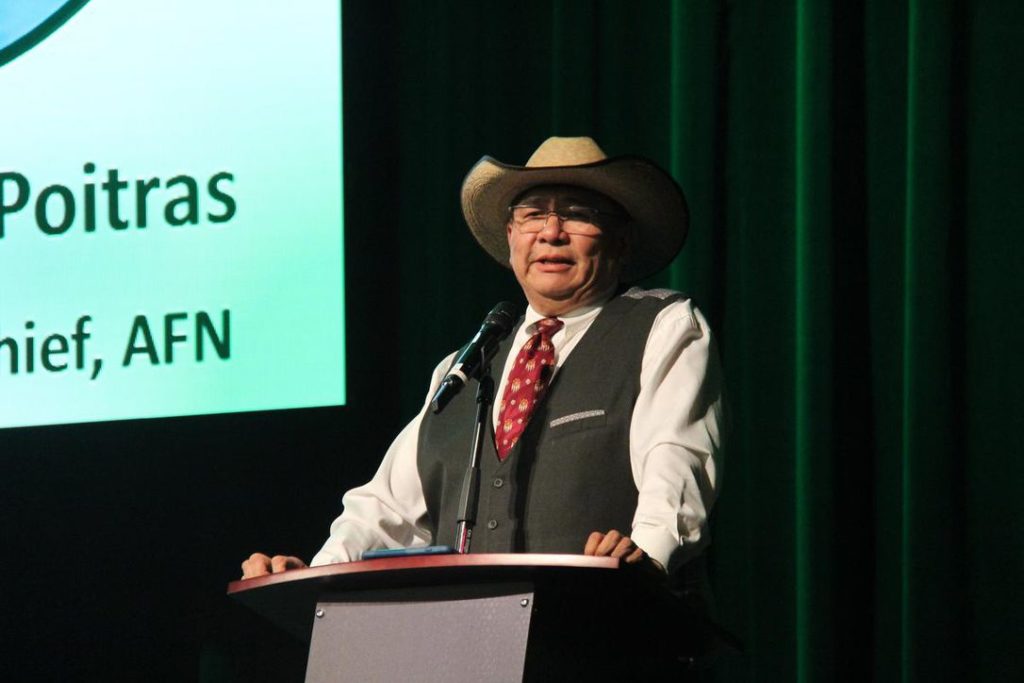

It appeared that many of the 500 delegates were at the conference on behalf of their local First Nations band councils, and no doubt many participants knew each other from previous nationally organized conferences and events. Most of the presenters were already involved in cannabis initiatives in their communities, and were there to do further networking and alliance building. AFN Regional Chief for Alberta, Marlene Poitras was on hand to welcome attendees to the conference.

Kahnawake Grand Chief Joseph Norton addressed the conference to rapturous applause and invoked the memory of the Oka crisis to support his efforts in passing a controversial law to regulate cannabis in his home community. Norton stated that his efforts in seeking to strictly regulate cannabis in Kahnawake were aimed at avoiding the economic chaos and disruption caused by the tobacco industry, considering that over 100,000 non-native people drive through his community every day.

First Nations Tax Commission representative Manny Jules was also present to argue that First Nations needed to acquire a share in the cannabis taxation regime. Indigenous movie star Adam Beach was there on behalf of the Indigenous Canadian Medical Dispensaries, as was his Smoke Signals co-star Dr. Evan Adams of Sliammon First Nation, who is also a cannabis advocate.

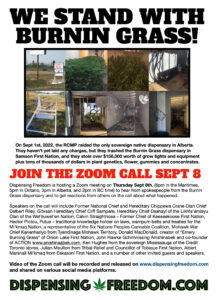

One of the conference highlights was the session featuring presentations from Indigenous business people who have been openly and publicly running dispensaries in their own territories. Rob Stevenson, the owner of Alderville’s Medicine Wheel Natural Healing and Jamie Kunkel, the owner of Tyendinaga’s Smoke Signals, both gave presentations discussing the benefits and challenges of their businesses.

Stevenson used his opportunity on the stage to play a ten minute video showcasing his operations and the benefits the industry has brought to his community of Alderville First Nation. Attendees seemed especially moved by the efforts that Stevenson has brought to language revitalization in his community, both in terms of a weekly class for his employees and of the use of Anishnabemowiin on product labels and in interacting with customers.

The presentations by Stevenson and Kunkel notwithstanding, most of the conference presentations were made by those either operating within Canada’s legal regime as Licensed Producers or seeking to join them. Pride of place in this regard was given to the presentation made by Lorraine White, the Akwesasne based Chief Compliance Officer of Seven Leaf, the first Indigenous owned and operated Licensed Producer on reserve. Seven Leaf has been working within Health Canada’s regulatory system for the last 5 years and has built a 64,000 square foot facility on Cornwall Island to grow and distribute cannabis, beginning in the spring of 2019.

The conference made sure to cover the medical issues surrounding cannabis, and a number of in-depth presentations made the case for the healing benefits of cannabis. Notable among those presentations was that of Dr. Shelly Turner, the medical director of First Farmacy Medical in Thunder Bay. Dr. Turner has issued over 4,000 prescriptions for medicinal cannabis over the past five years, and specializes in treating opiate addiction with harm reduction methods. Her co-panelist Dean Seneca, formerly of the US Center for Disease Control Tribal Health Research Office and the Great Lakes Tribal Epidemiology Center, provided an overview of the medical benefits and relative harmlessness of cannabis. Judging from the responses to the various panels, the audience was well aware of the medical utility and relative safety of cannabis, and saw these presentations as confirmation of their own experiences concerning the relative safety of cannabis and its benefits as a health modality.

The conference also had participation from Health Canada and RCMP officers. The incorporation of these viewpoints in the program led to a certain amount of tension that was evident in the interventions made from the conference floor. The Health Canada representatives were on hand to explain how the Canadian system operated, but were in no position to talk about the larger political issues concerning the failure of Canada to consult with First Nations about cannabis, and Indigenous self-regulation of the industry.

Todd Cain, the Director General of Cannabis Licensing and Medical Access at Health Canada, indicated that only eight First Nation communities had applied to Health Canada for licences, and acknowledged that the Canadian government needed to do better in consulting with Indigenous people. Audience members remained unimpressed, with one delegate pointing out that it was a typical Canadian approach to send lower level bureaucrats to take the heat, while not addressing the fundamental political issues concerning treaty rights and Indigenous self-determination as it relates to cannabis.

The panel featuring RCMP officers also avoided talking about the bigger political questions in terms of whether the RCMP would respect the sovereignty of Indigenous communities regulating their own cannabis industries. RCMP Corporal Richard Nowak took up most of the time on the panel to discuss protocols concerning tests for impaired driving, and Inspector Earl Nini, K Division Indigenous Liaison Officer for the RCMP, and Dwayne Zacharie of the First Nations Chiefs of Police Association kept their remarks extremely brief. Off-stage, however, Inspector Nini stated matter-of-factly that he and the RCMP respected the jurisdiction of First Nations governments in their own communities, and that the issue of cannabis regulation was ultimately a political issue, not a criminal one.

Notable for their participation were high level representatives of the largest cannabis players in the licensed Canadian system including Aurora, Canopy Growth and Tilray. These companies indicated their interest in working together with Indigenous partners while also showcasing their access to billions of dollars of market capitalization. One of the concrete offers of collaboration by these corporations was to work together with Indigenous leadership to ensure that the purchase of medicinal cannabis through their LPs would be freely covered by the Canadian government as part of their treaty responsibilities to Indigenous people.

Presentations were made by a panel of indigenous entrepreneurs involved in the hemp industry. Hemp is the same plant as cannabis, but differs in lacking the high THC concentration associated with psychoactive effects. Hemp is a quick growing plant that has many different uses as a fibre, food, and CBD medicine, and farmers across Alberta are seeing it as a major cash crop.

According to the Net News Ledger, Chief Isadore Day, summarized the conference as follows: “The issue of jurisdiction is the overwhelming priority coming out of this conference. Asserting our jurisdiction in the cannabis and hemp industry must be respected by mainstream industry and at all levels of government. Economic sovereignty, health and safety, and community risk and impacts are the main themes we heard. Most importantly, we heard there is a growing interest in establishing a national network of Indigenous producers and retailers in order to compete with the larger multi-billion dollar cannabis companies.”

The Saddle Lake Conference

The Saddle Lake conference was a smaller and more localized affair, held in St Paul’s Alberta, a two hour drive east of Edmonton on Treaty 6 territory. The conference was organized at the initiative of the Saddle Creek Cree Nation, following a previous event in August of 2018 in North Battleford, Saskatchewan. The agenda was focussed on exploring opportunities for building “A Strategic Path to Sustainable Economic Independence” for Indigenous communities. The five main “paths” being explored at the conference included food sovereignty, the growing of industrial hemp, clean water, renewable energy, and medicinal cannabis. The Saddle Lake conference had a $200 entrance fee and about 200 delegates attended.

According to conference organizer Cheryl Maurice, the conference was driven by the urgent needs of responding to “climate change and how everything is changing.” In the face of these challenges, Maurice believes that Indigenous people have a crucial role to play in helping to “bring back balance to mother earth.” Saddle Lake Councilor Sam Cardinal and Saddle Lake Economic Development Officer Winston Lapatak helped to host the conference, which was held as part of the Saddle Lake Crees’ efforts to create a better future for their 10,000 members.

According to conference participant Peter Cardinal of the Kikino Metis Settlement, “We want to move forward and support band members in promoting health and nutrition, and create employment. It’s about taking care of their members but also being a leader in developing these products and assisting other indigenous communities that want to move in the same direction.”

Cardinal indicated that when it comes to cannabis “very few of our communities have an interest in recreational cannabis, but many are interested in medicinal cannabis. And that has become an issue because of a lack of consultation with First Nations around the whole cannabis issue. We see what’s happening at Muscowpetung now. Now the government is saying that ‘you’re illegal and you need a provincial licence.’ The only reason they need a Provincial license is so that they can tax them. And the First Nation is saying no, we’re tax exempt, we’re Sovereign and you have no right to stop us from growing and using our medicines.”

The conference sought to blend the insights of both traditional indigenous medicine with the forms of plant based medicine being developed through the medicinal cannabis industry. Elder Hank Cardinal, a traditional medicinal healer presented on a panel with Dr. Paul Hornby, who is currently working with Legacy 420 in Tyendinaga to discuss the healing properties of plants.

The presentation of Tim Barnhart, the founder of Legacy 420, Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory’s first cannabis dispensary, showed what could be done with hard work and a willingness to push the boundaries of the possible. From modest origins in a plaza storefront, Legacy 420 is now the physically largest cannabis dispensary in Canada and has a yearly payroll of over $3.7 million. Barnhart outlined his “seed to sale” model and his efforts in building a lab and quality control processes that exceed Health Canada’s regulations.

Bob Holm of Strawman Farms made a presentation outlining the possibilities of using indoor growing techniques to produce high-value produce such as strawberries. Holm suggested that a key means for Indigenous peoples to achieve food sovereignty was to grow produce for the corporations looking to provide food for their workers in various extractive industries. These companies are increasingly realizing the need to co-operate with the Indigenous peoples whose land they are on, and they are willing to buy Indigenous local produce.

Terry Radford, the Vice President of Just BioFibre structural solutions was on hand with his Lego-like hemp building blocks which can be snapped together to quickly build ecologically friendly long term housing. The blocks are made from hemp, and they offer an affordable, mold resistant, and fireproof solution to the housing crisis facing many Indigenous communities.

As Peter Cardinal put it, “when we first seen those building blocks, I realized that this was the best housing solution that the Indigenous people could ever find. We can grow the materials needed for these blocks on our Indigenous lands on a tax free land base. As well as being able to process and manufacture those bricks should we able to get a manufacturing plant for it. We could help solve our own housing issues and use it as an economic venture to give us the profits to build our own homes.”

Derek Neepinak, a former Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs gave a presentation reflecting on his personal journey of building long term relationships for the common good. Still bearing some obvious pain from the ups and downs of his time in office, Neepinak, like many other Indigenous political leaders, sees the opportunity that hemp and cannabis can play in providing for a better future, and has created his own companies, Makwa Innovations and Acosis Cannabis Collective, to advance these interests.

The clear consensus at both conferences was that the cannabis and hemp plants offer profound opportunities for Indigenous people that must not be missed. Thankfully, the people necessary to take the Indigenous cannabis movement to the next level – the entrepreneurs, the political leaders, the financiers – were all present at these conferences and ready to make it happen. Expect 2019 to be a watershed moment, not just in cannabis history, but in the history of Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island.

Comments are closed.