TYENDINAGA MOHAWK TERRITORY – Tyendinaga Police Chief Ron Maracle recently showed up in person and armed to demand that Kanyenkehaka (Mohawk) dispensaries providing cannabis to a primarily non-native clientele, immediately shutter their doors.

Maracle represents a policing agency jointly funded by the elected band council (a department of the Canadian federal government) and the Ontario Provincial Police, a Provincial institution. The people whose economic activity Maracle is trying to shut down are Onkwehon:we people who have lived since time immemorial in their own homeland, and who are making a living by growing and selling a plant on their lands.

Maracle has insisted that he “is a man of his word” and says that he will “kick doors down” if the owners don’t shut down their businesses and comply with Canadian law. The dispensary owners have stated they will remain open to provide medicine to their patients, and have no intention of caving to what they see as foreign and illegitimate police pressure. The Longhouse for its part has met and initiated a decision making process concerning cannabis in the territory that dispensary owners say they will respect.

Tensions are high on all sides, and should police decide to raid stores while the traditional decision making process is underway, there is every possibility that serious conflict will erupt.

So that’s the background.

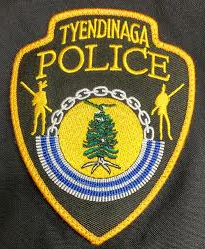

The focus of this story is to examine the Tyendinaga police logo which Ron Maracle and his officers carry on their uniforms. The logo is rich in symbolism, and by attaching it to their uniforms, it would appear to promise a certain type of police behaviour in relationship to the confederacy of Onkwehonwe nations united together by the Kayenere:kowa, or Great Peace.

Were Maracle – the employee of an outside police agency and someone who has not been given any authority by the people of the Longhouse – to follow the instructions printed on his own badge, he might discover an alternative way of ensuring a mutually beneficial outcome for all involved.

So let’s take look at the Tyendinaga Police logo and what it means.

In the centre of the emblem is the “tree of peace” with an eagle on top and four white roots. This emblem represents the political system of the Kayenere:kowa, under which people from many Indigenous nations take shelter. The origins of this powerful Indigenous confederacy sprang from the mind of the Peacemaker – an Iroquoian man born within what is now the community of Tyendinaga on the Bay of Quinte.

The white roots represent the spreading and reaching out of the Kayenere:kowa to all four corners of the world. The great white pine tree is a metaphor for this ever-growing system of peace and harmony. On the top of the tree is the eagle, always watching out and ready to screech a warning should danger approach. The whole of the yellow circle in the centre of the badge is a representation of the Iroquois Confederacy and its people and way of life.

The yellow is a symbol of sun light, and a representation of the total geographical territory of the Onkwehon:we. The Eastern door of the confederacy is where the sun rises, and the Western door is where the sun sets.

The next thing we see is a chain and a Two Row Wampum belt surrounding the symbol of the Confederacy. Iroquois people put a great deal of significance in such symbolism and barriers or guardians protecting the inside from the outside.

The Two Row Wampum is one of the oldest symbols in Iroquois cosmology and represents two separate paths operating in relationship to each other but never overwhelming or interfering in each other’s way. The white rows between these purple entities are symbolized by the concepts of peace, friendship and respect. This is the fundamental agreement that Iroquoian people made with European newcomers.

The second symbol represents the Silver Covenant Chain – a formal agreement between the Mohawks and the British crown. This agreement dates to 1710 and was reaffirmed as recently as 2010 when the Queen herself gave the Tyendinaga and Six Nations Mohawks a gift of silver hand bells engraved with the words: “The Silver Chain of Friendship 1710-2010.”

Iroquois people commonly used the metaphor of the rope or chain when making relationships with other nations. With the Dutch, their relationship was made with a hemp rope which eventually frayed and broke. With the French the relationship was an iron chain which was strong but rusted. With the British, the chain was made of silver and had to be routinely “polished” so the relationship would not become tarnished.

According to the Silver Covenant Chain agreement, if either party had an issue with the other, they could pull on the chain to get the attention of the other party. The two groups can then counsel, with the group that is pulling the chain organizing a feast and an offering gifts corresponding to the significance of the issue to be discussed. This process was called “polishing” the covenant chain.

Lastly, the logo shows two figures armed with rifles standing with their backs to each other but on opposite sides of the Two Row Wampum. The figure on the left is wearing a Gustowa – a feather headdress – with the three feathers identifying the wearer as a Mohawk. He is a member of the Rotiskenrakete – “those who carry the burden of peace” the men of fighting age who belong to the longhouse (often called in English translation the Warrior Society). The other figure represents a non-native person similarly armed with a long gun – an armed guard for the Crown.

These two armed figures are not in a situation of conflict with each other. Their guns point away from each other, and they are both protecting the system of the Confederacy. They are bound by the agreement of the Two Row Wampum as friends, and the Silver Covenant Chain functions as their dispute resolution mechanism.

The figures are of equal size and similarly armed. Neither one enjoys a monopoly on the tools of violence.

The final aspect of the badge is the yellow line around the image and the words Tyendinaga Police. By affixing their name in this way, the Tyendinaga Police are identifying with and taking responsibility for upholding the symbols and relationships described in the badge.

It is important to note that symbolic pictograms such as this badge carry a great deal of weight in all human societies. Regardless of whether you speak French, English, or Kayen:keha, if you understand the original agreements made upon this land represented by these symbols, you know exactly what the people who are wearing this badge are purporting to uphold.

The pictogram signifies responsibilities and relationships in a precise and concise way, and thereby also provides an answer for the question of how police should react to the supposed “public safety” concerns relating to the cannabis industry in Tyendinaga.

In my understanding, the badge shows that the two parties – the Rotiskenrakete and the armed guards of the Crown – have agreed to defend the Iroquois Confederacy together and to protect it by upholding the Two Row and Silver Covenant chain agreements.

The concept that the armed forces of the crown could walk into the circle of the Kayenere:kowa where Onkwehon:we people are peacefully engaged in their own economic affairs and make unilateral demands is preposterous. Chief Maracle has been given no sanction by the Rotiskenrakete or the Confederacy itself to act in this manner. He is a public servant of the British Crown and its Canadian subsidiary.

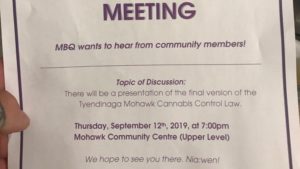

Making decisions about the usages of cannabis within Onkwehon:we territory is a matter for the political systems of those societies to resolve, as indeed they are doing by meeting to discuss this issue.

According to his own badge of office, Police Chief Maracle is violating the treaties made with the Onkwehon:we through his heavy handed and one sided threat to shut down Indigenous cannabis dispensaries.

The people of the ship have no business with what the people of the canoe are doing on their own land, unless it is directly harming them. And moreover, if they do have such concerns, rather than sending a police chief in to make threats, the more appropriate thing is to use political mechanisms such as the Silver Covenant chain to resolve diplomatic issues on a nation to nation basis.

This is indeed something that prime minister Justin Trudeau was elected with a mandate to do, and continually repeats as a talking point. Indeed, just the other day, the Federal government reiterated its desire to “re-commit to a renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government and Inuit-Crown relationship with Indigenous peoples — one based on recognition of rights, respect, and partnership.”

So why is Police Chief Maracle not upholding the honour of the crown and the wishes of the Prime Minister of Canada?

The mechanisms to initiate such nation to nation relationships may begin with the armed forces of the Crown tugging on the chain to alert the Rotiskenrakete of an issue that has come up. But that is not the same as entering the circle of the Kayenere:kowa and making threats to people’s way of life. The Kanyenkehaka elder Kanasaraken has explained how the Rotiskenrakete are a crucial component of initiating Onkwehonwe diplomacy and international relations, but ultimately the matter needs to come to the Longhouse people as a whole for discussion, which is where it currently is.

Even after the Longhouse began its deliberations, Police Chief Maracle has continued to add pressure on dispensary owners to shut down. Perhaps it is time for him and his officers to either reconsider their choice of action, or cease wearing a badge whose very meaning they are dishonouring.

Thoughts, comments, or alternative interpretations? Please leave them in the comments below!

Be First to Comment