From Ottawa Citizen link to article by JOANNE LAUCIUS, February 21st 2019

In less than a year, seven cannabis dispensaries have opened in Pikwàkanagàn First Nation.

The dispensaries opened without the blessing of any level of government, including the band council. About 450 people live on the reserve about 150 kilometres west of Ottawa. The dispensaries now employ about 90 people and pay wages of about $2.8 million a year. So far, none of the dispensaries have been fined or raided by police.

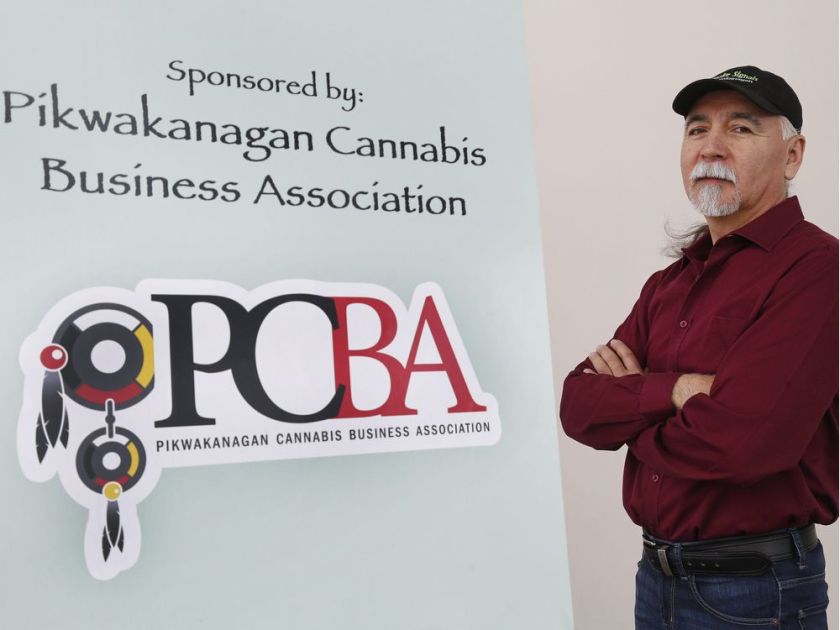

“We saw that the industry was moving forward, and if we didn’t move soon, the industry would leave us behind,” said Greg Sarazin, who opened Smoke Signals, the first dispensary in Pikwàkanagàn, in March 2018.

For the dispensary owners of Pikwàkanagàn, the heart of the matter is that the reserve is on unceded Algonquin territory. “We are doing it based on the sovereign right of the Algonquin people,” said Sarazin, who was chief between 1987 and 1989.

No First Nation in Ontario has the population base to apply for a licence. Like dozens of other dispensaries operated on Indigenous territories, those in Pikwàkanagàn sell unlicensed product. But the business owners say their products have been tested, they’re interested in community safety and they want to self-regulate. Six of the seven dispensaries have formed a business association.

“We found that there was so much that was undefined,” Sarazin told the attendees at a national conference on Indigenous hemp and cannabis conference on Thursday.

The conference attracted about 300 attendees from across Canada. Some are considering opening cannabis businesses. Some don’t want them in their communities. Others have already jumped right in.

Natalie Corbin, whose father-in-law owns Grassroots Healing, said the business has been growing so fast it’s hard to hire enough staff, and the business in local crafts has been booming. “We’re looking to hire security people. … We can’t keep up with the demand for dream-catchers,” she said.

Pete Bernard opened the most recent dispensary in Pikwàkanagàn in December, ripping up his yard to build the store. He didn’t want to wait for the jurisdictional confusion to settle to make his business move.

“The feds kicked it down to the province, the province kicked it down to the municipalities, but we’re not a municipality. The band can ban cannabis sales. But it hasn’t,” he said.

Although Bernard owns his house, he does not own the land it’s on. That created another wrinkle for him as a business owner and he had to finance the construction on his own.

Bernard said most of his customers come from Petawawa, Pembroke, Eganville, Killaloe and Renfrew, although some come from as far away as Ottawa. He believes there is room for even more cannabis businesses in Pikwàkanagàn.

But he admits that there’s also a level of risk.

“It’s scary when you know you can be shut down,” he said.

The ground zero of cannabis in Ontario is Tyendinaga, near Belleville, which is reportedly home to at least 50 dispensaries. The Tyendinaga Mohwak Council has held a series of meetings to discuss cannabis operations and decided to adopt interim regulations governing recreational cannabis, saying that the community wanted its rights and interests in the benefits of cannabis respected while protecting the community. A final regulatory regime is to be presented and ratified by April.

Alderville First Nation on Rice Lake near Cobourg has developed its own “cannabis model,” which includes standards for youth protection, health and safety, labelling and a complaints process. Last month, it presented a proposal for an ombudsperson to provide an impartial process for complaints about cannabis businesses from members of the community or the general public.

Besides the employment and economic spinoffs, the members of the Pikwàkanagàn Cannabis Business Association say they have already contributed to the local food bank, sponsored needy families and helped to pay for funerals.

“We’re not talking about a shady market of shady people,” said Bernard. “We want to build a hospice centre. We want to give back.”

Are there dangers to the community? Illicit opiates are already being sold in the community, said Bernard. “If you’re looking at what will destroy families, there should be more of a focus on opiates.”

Jay Greenwood, who operates Green Grass Oasis in a space that used to be his garage, said there would be more of a danger to Pikwàkanagàn if it were known as “poverty central” instead of gaining a reputation as “pot central.”

The association is looking for a band council resolution, the equivalent of a bylaw. But that hasn’t happened yet.

Chief Kirby Whiteduck did not respond to a request for an interview. But others who live in the area have been critical of the proliferation of dispensaries.

Michael Ilgert, who lives about two kilometres from Pikwàkanagàn, said he objects to seven dispensaries opening nearby without any political or police reaction.

“The rules should be applied equally. Even the city of Toronto could only get five licences,” he said.

Comments are closed.