It wasn’t so long ago that we remember when Tyendinaga had but one cannabis dispensary, one which was under constant threat of closure by the local constabulary.

Today there are over a dozen dispensaries in Tyendinaga. Like tobacco, there is scarcely one family on the territory that does not have at least one of its members directly benefitting from their involvement in the industry.

In 2016, non-natives purchased over $30 million in cannabis in Tyendinaga. Those cannabis dollars are bringing political as well as economic independence. The sense of economic self-confidence and growth in the community is palpable. The “green economy” is growing at the perfect time, as Onkwehonwe nations dust themselves off and prepare to resume their responsibilities in a post-Indian Act world.

But don’t get it twisted. The Indigenous cannabis industry is not a new thing by any means. This might be the first issue of the industry’s first magazine, but that’s only because of the longstanding repression and marginalization Indigenous people have been subjected to by the Canadian government.

With the “Columbian exchange” initiated in the 1490s, Indigenous people taught Europeans how to smoke both tobacco and the cannabis flower, and have long since provided all manner of people with these plants as trade goods.

On his second visit to North America in 1535, Jacques Cartier noticed hemp growing in Indian gardens in the as he floated up the St Lawrence river. 400 years later, along the same stretch of river, the Montreal Gazette reported in 1938 that Indian Act agents were ripping out 3500 pounds of marijuana plants a day from the community of Caughnawaga where “Marijuana has been growing as long as residents can remember.”

Today, along that same river, Onkwehon:we people are still growing and trading cannabis and using it for their own purposes.

Long before Ontario ministers announced the creation of an LCBO organized cannabis monopoly with 150 recreational stores across the Province, the Indigenous cannabis industry had spread its wings from Tyendinaga.

On June 21st, 2017 – National Aboriginal day – Medicine Wheel Natural Healing opened in Alderville First Nation with the tacit blessing of Chief and Council and has shot to local prominence. There are now four dispensaries open in Six Nations, one in Oneida of the Thames, one in Akwesasne, and First Nations Medicinal in Wahnapitae First Nation just held their Grand Opening on September 9th.

Things are moving to a whole other level with the upcoming Indigenous Cannabis Cup, to be held on the May 18-21st long weekend in Tyendinaga. The event will see live music, art, food, dancing, a Guinness Book of World Records ‘longest peace pipe” attempt, and of course a contest to determine Turtle Island’s best bud and cannabis derivatives.

The event will no doubt be a showcase for the state of the Indigenous cannabis industry in 2018, and a crucial gathering point for networking and organizing.

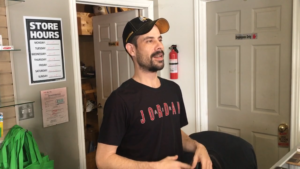

Smoke Signals in Tyendinaga, owned by Jamie Kunkel – a 25 year veteran of the Indigenous cannabis industry – is now offering free Smoke Signals franchises to indigenous medicine people.

So the cat is out of the bag. Indigenous people have an affinity for cannabis and other forms of natural plant based medicine and a deep distrust of the pharmaceutical and governmental system that has caused such damage to their people. They want in on what is an obvious growth industry with huge ramifications for everyone’s health and well being. And they want to partake in this industry on their own terms and have their own people benefit.

Maybe this could be Canada’s chance to show itself open to real and meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous people? The beauty of it is that Canada doesn’t actually have to do anything. It just has to respect that central tenet of the Two Row Wampum – non-interference in the way of the Indigenous system, as the canoe works out its own way to deal with the industry.

So far, what we are seeing is that Indigenous standards exceed those of their Canadian counterparts, and are focussed on maintaining an ethic of helping the people and providing medicine over making a quick profit. This stands in sharp contrast to the rush by government, pharmaceutical companies, and former narcotics officers seeking to get rich quick in the new “legal” industry.

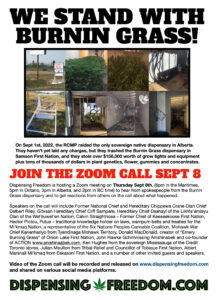

The recent announcement by the Ontario government that they will handle cannabis legalization through an LCBO style system of government run dispensaries raises the question of how the Provincial government will relate to on reserve cannabis dispensaries. The Province made very clear that they intend to raid and shut down any “illegal” dispensaries as they open their “legal” ones.

This is certainly bad news for the hundreds of non-native dispensaries that are already open in non-native communities. But the real question os about what will happen on reservation land. “Indians” are a Federal government responsibility and the Province has no jurisdiction on Indian reserves. And neither the Feds, Province or municipal government have had any success in closing down the “illegal” Indigenous tobacco industry. So there’s no indication that they will do any better in attempting to interfere with the Indigenous cannabis industry.

In our view, 2017 will be known as the year in which the Indigenous Cannabis industry became unstoppable. This magazine is an expression of the strength and determination of this industry and sees its purpose in informing and strengthening the industry as a whole. One arrow alone can be broken. Many arrows, bound together in unity cannot be broken. o

Comments are closed.