From resilience.org by Talli Nauman September 18 2023

PINE RIDGE, S.D.- A global enterprise based in Spain may seem an unlikely role model for a fledging American Indian initiative. But inspired by its success, Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm in Anishinaabeg territory is sowing the start of an intertribal cooperative consortium.

The new endeavor, called the Indigenous Hemp and Cannabis Farmers Cooperative, is laying the groundwork for the envisioned network. Farm owner Winona LaDuke and fellow founders intend to support the development of seeds, Indigenous standards, cultivation, value-added processing, appropriate technologies, and fair-trade markets.

LaDuke spoke to other Native hemp growers during a recent informational meeting at Red Cloud Renewable Energy Center, located not far from Oglala Lakota tribal offices. Alerting listeners to an upcoming fundraiser for the cooperative cause, she said, “I hope that some seeds are in the ground, and we will pray for gentle rains.” She announced the initiative at the fundraiser, a concert featuring folk singer-songwriter David Huckfelt at Madeline Island in Lake Superior.

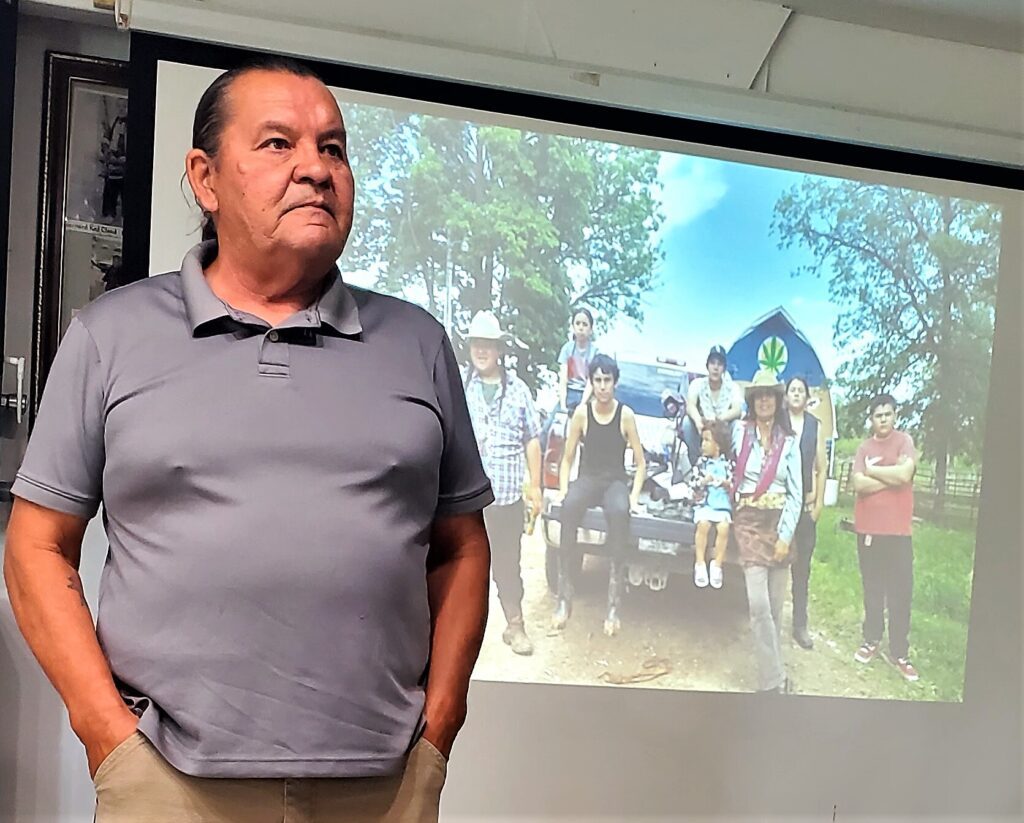

Workers at Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm pose with seeds for fabric, food, oil, and building material. Photo Courtesy of Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm.

Henry Red Cloud, an Oglala headman and founder of Red Cloud Renewable Energy Center, said this was his 14th hemp gathering. “I encourage our tribal membership to start a cooperative,” said the fifth-generation direct descendent of Maȟpíya Lúta, the principal Teton Lakota leader who negotiated the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

“We can have 10 acres here, 10 over there, 20 over there, five over here, and maybe a couple of acres over here, but we can do it together,” he urged. “Let’s go partner up. Let’s get down this road together. Some of us are way down the road already, so, you know, share that knowledge.”

Henry Red Cloud encouraged tribal members to walk the path of the New Green Revolution. (Talli Nauman Photo)

With those words, Red Cloud hit on the most glaring problems of the Native hemp challenge. He and other “hempsters” — as advocates of a hemp-based economy call themselves — must produce, transform, and market exponentially more than they do now. They don’t quite have a road map.

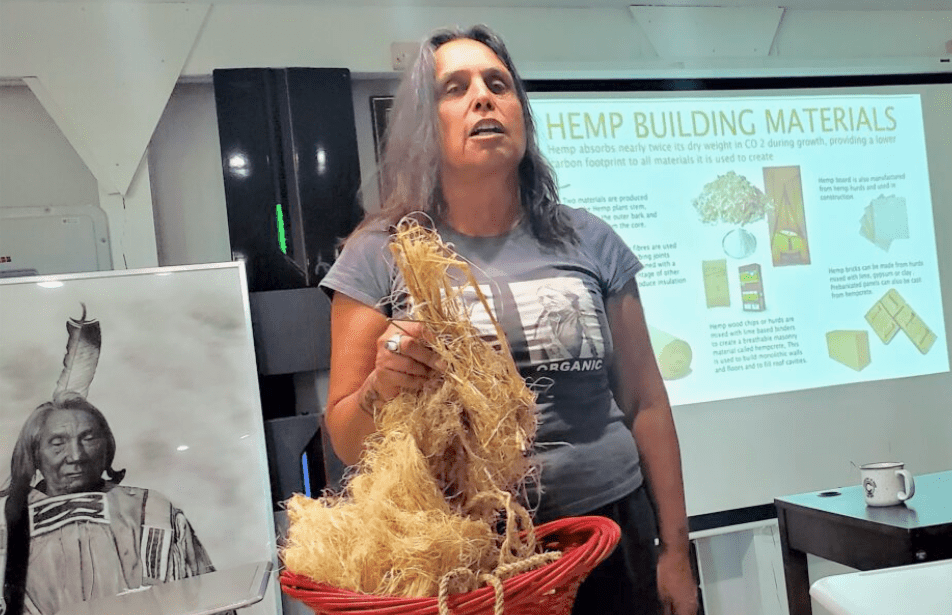

Hemp is a versatile building and textile material, with many other uses as well, including for the basic needs of fuel, food, and medicine. LaDuke touts its carbon sink potential in the field and its substitution as an input to save trees from paper or building industry demands.

The 2014 federal Farm Bill re-legalized hemp across the United States after a post-WWII moratorium on growing it. But almost a decade later, tribal citizens, who are among the most interested in its possible community benefits, are barely cutting their teeth in the business.

For example, Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm, in collaboration with the non-profit Anishinaabe Agriculture Institute, has harvested hemp for eight years. Yet they have only seeds and stalks to show for their troubles. They purchased a processor they needed only by importing it from China. They are trying to obtain abandoned mills to weave textiles. In an experiment with one bale of hemp, they found that they had to send it to North Carolina, then Virginia and Mexico for a finished fabric product. It wasn’t until 2023 that they raised their first hemp-and-lime (hempcrete) walls.

Veteran hempster Alex White Plume has long advocated for diversifying reservation hemp activities. “If we could turn the dollar over seven times within our communities, and then the chain reaction starts, we’ll start a local economy,” he said.

Alex White Plume shares experiences of hemp industry in Indian Country. (Talli Nauman Photo)

However, White Plume pointed out another hurdle to overcome. Speaking at the Pine Ridge meeting, the former Oglala Sioux tribal president said his reservation’s regulations have become too onerous for hemp production and processing. “I know how to grow hemp, there’s no trick to it,” he said. But with a 55-page ordinance, “it’s just impossible.” He said he hopes other local growers will help him convince the tribal council to convert the regulations into voluntary guidelines.

LaDuke, a Harvard-trained economist, has been cultivating the idea of an intertribal cooperative consortium since visiting Spain in 1981. There she discovered the Basque Country and the employee-governed Mondragon Corp., she told Buffalo’s Fire.

She maintains the road to prosperity depends on raising enough hemp and processing it into fiber products in a vertically integrated Mondragon-style commercial network. A two-time Green Party presidential running mate and founder of several successful Indian Country non-profits, she encourages fellow Native hemp growers to join hands.

“In the nonprofit sector, the wealth stays in the nonprofit, and having done that for 35 years of my life, I now want to see how to get more generational wealth into my community,” LaDuke said.

Winona LaDuke uses processed hemp fibers like these and shows their application in the building industry. (Talli Nauman Photo)

The much-studied Mondragon Corp., the world’s largest conglomeration of cooperatives, ranks first in Basque business performance ratings and tenth overall in Spain. Founded in 1956, it has grown to encompass 95 separate companies, owned by some 80,000 employees on every continent.

The model enterprise boasts revenues on a par with those of Kellogg’s and Visa. No top manager makes more than six times the entry-level pay, sharing profits where needed among participants instead. To bolster economic sustainability, personnel operate their own credit institution, plus 14 R&D centers.

Mondragon Corp. headquarters are in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, one of 17 such jurisdictions that make up Spain. Like tribal governments in the United States, the autonomous units are second only to the federal government, in terms of the countries’ hierarchies of authority. Known in the Native language as Euskadi, the community located in the Pyrenees Mountains has 2.1 million residents, most of whom trace local ancestry to times before Roman Conquest.

Mondragon personnel operate their own credit institution. Photo Courtesy Mondragon Corp.

“The people that they call Basque own all kinds of businesses. They grew them out of their Indigenous values and proceeded to build wealth in their community,” LaDuke said. Mondragon Corp.’s Indigenous roots, size, and wealth are not the only assets that attract the Pine Ridge meeting goers. Its social justice principles resonated with participants from tribes in Minnesota, as well as in North Dakota and South Dakota, as they hope to launch a similar enterprise.

“Social values are embedded in its core working practices and drive it forward,” concluded a case study of Mondragon Corp. conducted by The Young Foundation in the United Kingdom. A focus on people and solidarity has underpinned the cooperatives’ ongoing development for more than six decades.

Thanks to Mondragon Corp., the Basque region claims the lowest levels of poverty and economic inequality in Spain, the non-profit Cincinnati Union Cooperative Initiative, Co-op Cincy, determined after a May fact-finding mission. The New York City-based business source Fortune Magazine included Mondragon Corp. in its “Change the World” directory. That list is comprised of more than 50 successful international businesses and initiatives that are “taking on society’s unsolved problems.”

Fortune exalted Mondragon for demonstrating “no business succeeds alone” and the importance of “collaboration among companies.” Its cooperatives have helped to combat the COVID-19 pandemic by starting up new businesses and proactively placing their technical resources at the service of others, the magazine noted.

Hemp’s prospects for reducing global warming while turning around fossil fuel dependence led LaDuke to champion it as the cutting edge of a New Green Revolution.

The original Green Revolution, attributed to the University of Minnesota Agronomy and Nobel Prize winner Norman Borlaug, is the precursor of today’s transnational agribusiness monocropping. It relies on petroleum supplies to feed the world and makes for a hydrocarbon economy, said LaDuke. In contrast, she added, a carbohydrate economy would result from an allied grassroots producers’ movement.

This story was originally published by Buffalo’s Fire and is reposted here with permission from the author.

Comments are closed.