From The Cap Times by Natalie Yahr November 12 2022

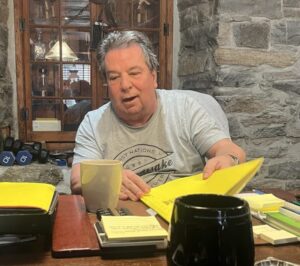

Entrepreneur Rob Pero is on a mission to claim a piece of the growing cannabis market for Native Americans.

It’s a natural fit, said Pero, an enrolled member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Not only have some tribes been using cannabis for medicinal and spiritual purposes for centuries, but the people and the plant have been similarly maligned.

“There (are) so many parallels between… both of these entities which have faced a lot of stigma and need a lot of deconstruction of these narratives,” Pero said.

In 2018, the longtime marketing professional and serial entrepreneur saw his chance to change that — and turn a profit. After nearly 50 years of prohibition, the 2018 Farm Bill made it legal to grow hemp, a form of cannabis which carries lower levels of THC, the chemical that creates a high.

It wouldn’t be long before the industry would be oversaturated, Pero predicted.

“So, while it was still fresh and new, could I create a brand and sort of a movement for us as Indigenous people to take ownership of this plant that is indigenous to our land and goes back thousands of years with cultural patrimony to some tribes?”

A joint venture

Pero launched the CBD brand Canndigenous in 2020, planting 10 acres of hemp just outside Cambridge. As far as he knows, it’s the first independent, Native American-owned hemp company in Wisconsin. He also bought Deerfield CBD apothecary The Hemp House, relocated it to 226 W. Main St. in Cambridge and renamed it Ripley Green.

The Canndigenous harvest becomes CBD salves, oils, lip balms and gummies, as well as a variety of single-strain CBD flowers for customers to roll or process on their own. Ripley Green sells those products, as well as CBD and hemp-derived THC products from companies like Hometown Hero and BioSpectrum, all screened by Pero and general manager Lindsay Wehmeyer.

Canndigenous has also begun offering a “bud bar” service for private events and open-air cannabis markets. It’s similar to a pop-up cocktail bar, but instead of alcohol, Wehmeyer serves up hand-rolled hemp flower joints.

The two companies are guided by the Ojibwe instruction to do all things “in a good way,” Pero said, as well as the Iroquois principle that all decisions must consider the effect on the next seven generations and pay respect to the groundwork laid by the preceding seven generations.

But stating those values is just the beginning, Pero said. “Anytime you’re gonna take your own roots and build it into your business model, I think you’re putting a responsibility on yourself to be accountable to what it means to have pillars of your brand. Are we really adhering to doing things in a good way? … Are we really living and breathing what we’re talking about?”

So far, those principles have led Pero to make the two businesses as transparent as possible, and to strive for environmental sustainability, returning plant waste back to the fields and using joint-storing “doob tubes” made from plastic waste gathered from the ocean.

Though Canndigenous does not currently plan to begin producing its own hemp-derived THC products, Pero plans to begin growing marijuana if recreational or medicinal marijuana is one day legalized in Wisconsin. He’s also exploring the possibility of selling CBD products on the tribal market, or even teaming up with marijuana growers in other states to produce THC products for the tribal market.

Out to grow the industry

Now Pero is looking beyond his own business, hoping to grow the cannabis industry and “light a path” for other Native Americans — from individual entrepreneurs to tribal governments — to follow.

Earlier this year, he founded the Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association with the goal of creating “an equitable, just, and sustainable Indigenous cannabis economy.” The group is hosting the first National Indigenous Cannabis Policy Summit in Washington, D.C. next week.

“I can only do so much as a business owner because I’m a for-profit business,” Pero said. “But advocacy, I’ve seen it truly work.”

He’s also teaming up with other businesses to take on major industry challenges. In September, Canndigenous and about 20 other businesses and universities were awarded a $15 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to expand the market and test the environmental benefits of growing and processing hemp on an industrial scale. It’s one of 70 projects funded through the agency’s $2.8 billion Partnership for Climate-Smart Commodities pool.

Hemp isn’t a new crop in Wisconsin. In the 1940s, the state was one of the country’s largest producers of hemp, and home to more than 40 hemp mills making rope, cloth and other products. But demand shrank after World War II, and the state’s last hemp mill closed in 1957. Congress dealt a death blow to the industry in 1970 when it banned marijuana and hemp in the Controlled Substances Act.

With the new grant funding, the team aims to rebuild some of the infrastructure lost in the decades since, and test innovative ways of using the plant, such as in “hempcrete,” an alternative to concrete with a much smaller carbon footprint.

For his part of the project, Pero will team up with a local corn and soybean farmer to plant 100 acres of industrial hemp, ten times the maximum acreage he’s planted before. “This isn’t like growing small-batch CBD where people have to go hand-pick it and trim it,” Pero said. “This is like combine seeding, real deal farming, and I need help.”

If successful, Pero said, the project will prove that hemp can once again be a viable commodity crop. That would offer new opportunities not just for existing industrial farmers, but also for the Native American tribes that hold much of the country’s undeveloped agricultural land, Pero said.

“That could be scalable. That could be 1,000 acres. That could be 2,000 acres. That could be tribes and other tribal member-owned businesses and non-Native businesses that want to figure out how to fit into that model,” Pero said.

“That’s what’s exciting about it … This collaboration between these small batch cannabis connoisseurs and the farming industry … could be humongous.”

The four questions

What are the most important values driving your work?

For me, it’s building community. I think there needs to be more connection and finding space for common ground. All things will be better from that. The other aspect is transparency. In an industry where a lot of things happen behind closed doors, we’re trying to open that door up and really show people the inner workings of how to get things done, and that there are people willing to help you along the way.

How are you creating the kind of community that you want to live in?

Getting uncomfortable. I own a bunch of businesses and I do a bunch of stuff in communications, but it doesn’t mean that I love to communicate. But I know that, as a dad, as a husband, as a business owner, as a manager, it’s important for me to be a steward of my community. It’s important for me to build bridging conversations instead of build breaking conversations. I think you can easily get into a lot of those conversations that can go awry in a state like ours. So I think the more people that are trying to build relationships, the better.

What advice do you have for other would-be entrepreneurs?

Ask for help. You can’t do it all. Don’t be afraid to share your ideas. Take chances. Golly, I mean, all those lame cheesy things that you read about other successful people and how they failed a million times — it’s all true. There’s never going to be anyone to pat you on the back either. So, even if you’re doing all this really cool stuff or you have one big success, don’t expect some grandiose hand on the back telling you that you did it. It’s a constant grind. You either want that grind or you don’t, but that grind is part of business.

Are you hiring?

Yes. We are always looking for business development, cannabis executives, people who want to collaborate with what our brand or our shop is doing. And (we’re also looking for) trimmers, people that want to come out and get their hands sticky. Harvest usually happens the first week in October, and then the drying takes between four to six weeks, and then the trimming happens after that. So there’s always seasonal work, but there’s long-term careers in this space too.

Share your opinion on this topic by sending a letter to the editor to tctvoice@captimes.com. Include your full name, hometown and phone number. Your name and town will be published. The phone number is for verification purposes only. Please keep your letter to 250 words or less.

Comments are closed.