From thestar.com Original Article by Wendy Gillis June 28 2020

For more background on this story see Dispensing Freedom’s previous coverage here

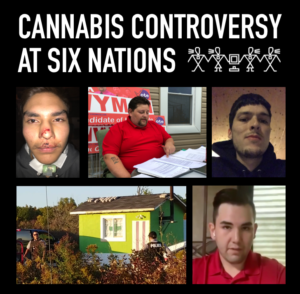

Dallas Porter said the Six Nations Police Service officer grabbed him and slammed him onto the ground. Suddenly, the teen’s life was in peril.

The survivor of a past suicide attempt, Porter, 19, requires a tracheostomy tube to breathe. If it shifts or becomes blocked it could obstruct his airway, causing him to suffocate. It’s critical that he avoid lying on his stomach — precisely what he says he was forced to do by police.

“Six Nations Police smashed my face into the ground multiple times,” Porter said in a written summary of the incident, prepared for the Six Nations Confederacy Council. “After the police slammed me into the floor I was then stood up and slammed into the wall.”

Porter said his ordeal began with an Oct. 9, 2019, raid of an alleged cannabis dispensary on Six Nations of the Grand River territory. During the incident, Porter and four other young men — who all live on Six Nations — allege at least six officers used unjustified force while arresting them on cannabis charges.

Porter, who is not involved with the dispensary and arrived only moments before police, suffered a broken nose. His friend, Ryan Davis, was diagnosed with a concussion after he says he was punched in the head by an officer — “I remember saying, ‘Stop, you’re hurting me,’ like screaming (it),” Davis said.

The three other men who were arrested say they were also roughed up and remain traumatized by the incident, especially police treatment of Porter.

“Dallas could have died, easily, the second that somebody put his face into the ground,” said Alyziah Styres, who listened as Porter struggled to breathe in the back of a police car, his tracheostomy tube partially obstructed. He and Davis said officers refused to get the backpack containing Q-tips needed to clear Porter’s breathing tube.

“He was bleeding all over himself and I couldn’t do anything to help him. I was like, ‘How is this right’?”

United in anger, the men launched complaints about their treatment by officers — but soon realized there was nowhere to turn except the police force itself. Like many of Ontario’s First Nations communities, Six Nations is outside the jurisdiction of the province’s police watchdogs.

“They’re untouchable,” Mike Davis, who was among the group arrested, said of the Six Nations police in a recent interview. “And no one gets to investigate them but themselves.”

Amid a national reckoning about policing, in the wake of two recent fatal police shootings of Indigenous people in New Brunswick and the violent arrest of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam, the men are speaking out about what they say is a lack of accountability for police actions in their home territory.

“As a member of this community, I deserve the right to feel safe and protected by our police service. However, I am left feeling violated by the very people who are supposed to be safeguarding our community,” Ryan Davis wrote in a complaint to former Six Nations Police Chief Glen Lickers late last year.

Neither the Six Nations Police Service nor Acting Deputy Chief David Smoke, the officer who investigated the complaints, responded to multiple emails and phone calls from the Star.

First Nations police services are often staffed by Indigenous officers, though not exclusively.

If the raid and arrests had occurred outside Six Nations’ territory, Porter’s injuries would have automatically prompted an investigation by the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), which probes serious injuries and deaths involving police.

Meanwhile, Styres and the Davises — all of whom were arrested and charged under the Cannabis Act, although the charges against Porter and Styres have been stayed — could have lodged complaints with the Office of the Independent Police Review Director (OIPRD), the province’s civilian police complaints agency.

With no options available, the men asked Six Nations police to bring in a third party, such as an outside police service, to investigate. They said when police refused, they turned to the Six Nations Confederacy Council.

“They are investigating themselves and I fear that this incident will get dismissed, as it is not being taken seriously,” Porter wrote in a letter to the council in March.

“I also fear that the Six Nations police will do this to someone else, and the next person might not be so lucky.”

Later that month, the men were advised their complaints had been dismissed, without them ever being interviewed.

“I am dismissing this claim that you were treated inappropriately or unlawfully when you were arrested,” Smoke wrote in a letter addressed to Ryan Davis and reviewed by the Star.

Tamar Friedman, a Toronto lawyer representing the men, said it’s not clear who was interviewed, what documents were reviewed or how the police service came to its decision. If the OIPRD or SIU had been investigating, the complainants would have been interviewed and there would be a detailed report explaining the process and the outcome, she said.

Instead, there has been “complete lack of accountability” surrounding what she called a disturbing use of excessive force.

“This lack of oversight and accountability can only embolden (Six Nations Police) officers to participate in further abuse,” Friedman said.

The absence of civilian police oversight in First Nations communities has been well documented, most recently by Ontario Court of Appeal Justice Michael Tulloch in his 2016 review of police oversight. Through consultation with Indigenous communities, Tulloch said the “desire for appropriate civilian oversight of First Nations policing is clear.”

“The exclusion of First Nations policing from civilian oversight results in many First Nations communities not having access to the same oversight mechanisms as other Ontarians,” Tulloch wrote.

His report recommended the province consider expanding the mandates of the SIU and OIPRD to include First Nations policing, “subject to the opting in of individual First Nations.”

According to a spokesperson for the Ministry of the Solicitor General, incoming changes to Ontario’s policing legislation will create civilian police oversight of officers employed by First Nation boards that choose to opt in.

When the new policing legislation comes into force — the regulations are still being drafted and there is no timeline — it will establish the Law Enforcement Complaints Agency (LECA), replacing the OIPRD. It will also create a new oversight option called the inspector general, which will monitor and inspect police services and boards, including those in First Nations communities that have opted in.

Changes are coming, too, under the forthcoming SIU Act, said a spokesperson for the Ministry of the Attorney General, including giving the watchdog the “authority to enter into voluntary agreements with First Nations in Ontario to conduct or assist with investigations.”

Although that may mean good news in the future, it doesn’t help the men from Six Nations. Friedman is still asking Six Nations police to allow an outside body to investigate her clients’ complaints.

“We also hope the (Six Nations police) will immediately start working with the Six Nations Elected Council and Hereditary Council to find new practices that will restore police legitimacy in the community, not only in the way they respond to complaints, but also in the way they police,” Friedman said.

Since police dismissed the men’s complaints, the Six Nations Elected Council has signalled an intention to launch a review of both the police service and its commission, although it’s not clear if the men’s complaints about the raid played a part in that decision. The Star sought comment from the elected council but did not hear back.

According to Turtle Island News, the council said in May that there are several concerns about the police service, ranging from ignored emails to community complaints about a problem with the Six Nations police culture.

Porter and his friends are hopeful the review could bring accountability and say Indigenous communities should have access to police oversight when it’s warranted.

“I just want justice, and that’s something that hasn’t been on this reserve for a very long time, if ever,” said Mike Davis.

Erick Laming, an Algonquin First Nation PhD candidate studying criminology at the University of Toronto, has interviewed Indigenous people living off and on reserve about their interactions with police, and says he’s heard many first-hand stories about police violence and victims having no recourse.

Allegations of police use of force against Indigenous people happen “way more often than the public even knows about,” Laming said.

“A lot of times, Indigenous people don’t want to come forward because they don’t want the attention, they are afraid (they’ll be) targeted even further and, sadly, they just take it,” he said.

Stacia L. Loft, who served as an elected band councillor for the Tyendinaga Mohawk Council, Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, agreed that Indigenous people negatively affected by police interactions should have access to recourse.

But what that looks like — whether it be an oversight body, community council, a commissioner or ombudsperson — should depend on each community’s distinct needs. Importantly, she said, Indigenous communities must be supported, including financially, to develop whatever system is best.

She added that while some communities might choose to opt into already existing oversight bodies like the OIPRD, this should not be the default, as trusting outside agencies “has not always worked well for Indigenous peoples.”

“I strongly believe that Indigenous communities can identify and develop their own responsive and culturally appropriate solutions,” Loft said. “In doing this, communities will have ownership over their information, processes, decisions and outcomes.”

Comments are closed.