From Leafly link to article by BRUCE BARCOTT October 30th 2018

On a recent Thursday afternoon the sales floor of Medicine Wheel Natural Healing, a cannabis store in the Ontario First Nations town of Alderville, bustled with a dozen customers browsing the store’s flower, pre-rolls, edibles, and concentrates.

Budtenders—most of them members of the Anishinaabe band of the Ojibway nation—hustled from client to cash register and back again.

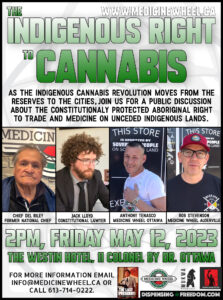

Rob Stevenson, the store’s owner, pointed out some popular products to a visitor. “We’ve got infused chocolates, gummies, and a range of beverages,” he said. “We should have our first topicals available next month.”

That range of products is one of the main reasons Medicine Wheel—and a half-dozen other cannabis stores along Alderville’s famous Green Mile—is seeing a parade of customers these days.

Two weeks into Canadian cannabis legalization, one of the main complaints about the new regime continues to be the wait for edibles, which the government is targeting to introduce by October 2019.

Edibles aren’t entirely unavailable, though. A number of First Nations entrepreneurs have established recreational cannabis stores that offer infused food and beverages, which are legal under the laws of Canadian indigenous sovereignty. And that’s transformed Alderville into a destination shopping district.

Putting Alderville on the Map

Two years ago this town was unknown to most non-indigenous Ontarians. A sleepy burg of about 300 people near Rice Lake, between Toronto and Ottawa, Alderville has been the home of the Anishinaabe Ojibway people since the 1830s.

The Green Mile started as an idea for a simple seed shop. “When the government announced that everyone would be allowed to grow four plants at home, I figured people were going to need seeds,” recalled Rob Stevenson, a local small business owner. So he attended a meeting about cannabis and indigenous sovereignty in Tyendinaga, the Mohawk reserve on the Bay of Quinte.

“I got inspired at that meeting,” Stevenson said. “We heard stories about how cannabis was helping people. We heard about how it could help communities economically, through direct employment and the spinoff companies around the industry.”

A Booming Year in the Business

Stevenson opened Medicine Wheel Natural Healing as a medical cannabis dispensary on June 21, 2017, “and since then we’ve been just rocking it. We’re up to about 15,000 registered clients, between 200 and 250 new clients every day.”

The economic boom set off by his store is clearly evident on the reserve.

Medicine Wheel itself employs a staff of 30 full time employees, 20 of whom are indigenous.

“This community has 300 on-reserve members,” said Stevenson. “So with just this one dispensary, we’re having an impact on our community.”

A small outbuilding in the store’s parking lot serves as the headquarters of Mukwa Security, a new ancillary company established to service the local cannabis industry. Across the street, a single building holds Greener Grass Dispensary, Sacred Vapors, and Greentree Hydroponics. Down the road a ways are The Green Room, Neejee’s Natural Medicine, and Totem Pole Dispensary.

The town’s most distinctive cannabis store is Healing House, an establishment consisting of two joined shipping containers that have been painted by a professional graffiti artist.

Friendly Competition

Despite the competition, the stores remain on good terms. When other dispensaries started opening in the wake of Medicine Wheel’s success, friends asked Stevenson if he was disappointed at others cutting into his business.

“No, man, that makes me happy,” Stevenson told them. “That means more people are getting involved and more people are going to be able to prosper.”

First Nations Rights and Cannabis

For the Green Mile shops, transparency and open communication have been key to coexisting within the law and the community. Before opening his own store, Rob Stevenson presented his business plan to both his family and the tribal chief and council, all of whom gave their tacit blessing to the project.

The sovereignty of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples rests mainly on two documents, the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982.

Section 35 of the 1982 act recognizes the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, but doesn’t go into specifics. Subsequent court decisions have established rights of fishing, logging, hunting, indigenous land title, and treaty enforcement. For the past 20 years the Government of Canada has maintained a policy of recognizing the right of indigenous self-governance—and that’s where the legality of tribal-regulated cannabis stores fits in.

“We’re adding cannabis to our repertoire of indigenous medicine,” Stevenson said, and operating cannabis stores acts as expression of First Nations sovereignty.

Staying on the Legal Side of the Law

Local police don’t always agree with expressions of sovereignty, however. In the United States, local police have shut down some cannabis companies operating on indigenous land, most notoriously in the case of the Flandreau Santee Sioux tribe of South Dakota.

Shortly after opening, rumors of an impending law enforcement raid on Medicine Wheel led Stevenson to schedule a meeting with the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP). First Nations are not bound by the laws of any particular province, but through a government-to-government agreement, the OPP enforces the rules and regulations on the First Nations reserve.

“I went to the OPP and gave them a similar presentation to the one I gave to chief and council, showing them why I’m doing this and how I’m doing this,” Stevenson recalled. “It was received very well. I met with the police quite a few times. The police would stop in a few times just to see how things were going. I remember the first couple times the police came in, and it would clear the store, clear the parking lot. After a while, though, people realized they were just there to talk and observe.”

“Those were helpful sessions,” Stevenson added. “They let the police see firsthand what we were doing. They saw that we’ve got a huge range of people coming in from different backgrounds, not just the typical stoner persona. We’ve got a lot of seniors, women, people of all ages.”

Becoming a Community Center

Nowadays, with the business thriving, the Medicine Wheel staff is doing more to make the store a community resource. The store posts an Ojibway word of the day and hosts a weekly indigenous language class for staff members. “By bringing in customers from all over the province, that allows us to introduce people to our culture,” said Stevenson.

The staff is incorporating First Nations traditions into the life of the store, too. On really busy days, when budtenders are getting stressed, a manager will call for a smudge. Among the Ojibway, a smudge is a ceremony using the energy of sacred plants to remove negative energy and restore centering and healing. “We’ll slow everything down, all the staff will smudge—we’ve even had customers say, ‘Do you mind if I join in?’”

Cannabis Revives a Language

The revitalization of the Ojibway language has become one of Medicine Wheel’s second bottom lines—a measure of their positive impact on the local community.

“My goal is to reach a point where our staff interact in our language,” Stevenson said. “As we develop further, we’re going to be adding more of our own products and putting indigenous names on them, in hopes that our customers will be coming in and ordering products using our language. I’m pretty excited about that.”

One of the first phrases the Green Mile shops of Alderville are moving into the wider world: green mashkiki.

Mashkiki is the Ojibway word for medicine, and green mashkiki is how the Anishinaabe Ojibway refer to the cannabis plant. So really, it’s not the Green Mile. It’s the Green Mashkiki Mile.

Comments are closed.