Reversing drug prohibition and legalizing cannabis is a historic feat. But as Boyd points out, before we turn the chapter, drug prohibition needs to be “understood as a social justice and human rights issue. The question is how will the government address the historic violence and injustice of drug prohibition?”

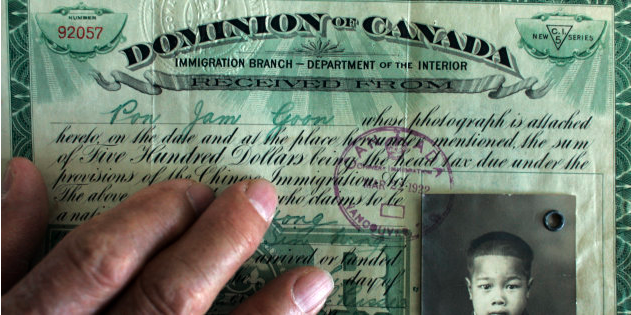

Chinese-Canadians were the target of early anti-drug laws.

Canada’s recent legalization of marijuana has spurred some heated debates, but one topic many Canadians aren’t talking about is the country’s dark history of prohibition.

In her book Jailed for Possession, Catherine Carstairs, chair of the history department at the University of Guelph, details the history of illegal drugs in Canada, beginning with a set of policies that demonized ethnic minority communities, especially Chinese immigrants.

The first wave of Chinese immigration began in British Columbia during the gold rush in 1858; while the second major influx of Chinese immigrants to the province came as labourers for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, beginning in 1881.

When the construction of the railway was finished in 1885, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act — now known as the Chinese Exclusion Act — instituting a head tax of $50 per person. By 1903, it was raised to $500 per person.

While Chinese immigrants provided a much-needed labour force for Western Canada, they were seen as problematic and undesirable. By the end of the 1800s, opium was linked to Chinese men who were depicted as endangering Canada.

“Anti-Chinese agitation became a powerful force in British Columbia politics,” wrote Paul Kee, a Chinese-Canadian historian, in Library and Archives Canada’s “History of Canada’s Early Chinese Immigrants.”

“Blaming Chinese immigrants when the economy turned bad became a way of organizing migrants from Great Britain and Europe around the idea of ‘white supremacy,’ captured best in the phrase ‘White Canada Forever.'”

(“White Canada Forever” was a rallying cry, movement and popular song in parts of British Columbia at the time advocating for a “whites only” country. A section of the song’s lyrics reads: “We welcome as brothers all white men still/But the shifty yellow race/Whose word is vain, who oppress the weak/Must find another place.”)

Yee writes: “[W]hite British Columbians also firmly believed that their way of life was better than all others. They saw China as a weak nation of backward people who could never learn to live like white Canadians. Moreover, they said that Chinese people carried diseases and other bad habits (such as smoking opium) that threatened Canada’s well-being.”

The Opium Act

In 1907, the anti-Asian sentiment culminated with riots organized by the xenophobic Asiatic Exclusion League. Over 8,000 white men stormed through Vancouver streets, damaging Chinese and Japanese businesses and enclaves.

At the head of the protest was a large banner stating: “Stand for a White Canada” as the men marched to City Hall,” Susan Boyd writes in Busted: An Illustrated History of Drug Prohibition in Canada.

“Fears about wanting Canada to be a white nation… pushed along our first Opium Act,” Boyd told HuffPost Canada in a phone interview.

William Lyon Mackenzie King, federal deputy labour minister at the time, was called in to investigate the aftermath of the 1907 riots. While conducting interviews, he spoke with Chinese anti-opium activists and concluded that opium-smoking was an increasingly dangerous trend among white people.

King writes in an archived government report on July 1, 1908:

“The Chinese with whom I converse on the subject, assured me that almost as much opium was sold to white people as Chinese, and the habit of opium smoking was making headway, not only among white men and boys, but also among women and girls… To be indifferent to the growth of such an evil in Canada would be inconsistent with those principles of morality which ought to govern the conduct of a Christian nation.”

A year after the riots, the labour minister tabled a bill prohibiting the manufacture, sale or import of opium except for medicinal purposes.

“Blaming Chinese-Canadians for the degradation of white youth through drugs, (the right-wing anti-drug crusaders) demanded harsh new drug legislation, as well as Chinese exclusion,” Carstairs wrote in a 1999 article, published in the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History.

As a result of the anti-drug campaign, maximum sentences for trafficking and possession opium increased from one year to seven in 1921.

Possession and trafficking laws disproportionately targeted Chinese Canadians, Boyd writes in Busted, leading to the expulsion of 671 immigrants under the act over the next decade. By 1922, over 60 per cent of all drug convictions were against Chinese residents.

The Narcotics Drug Act

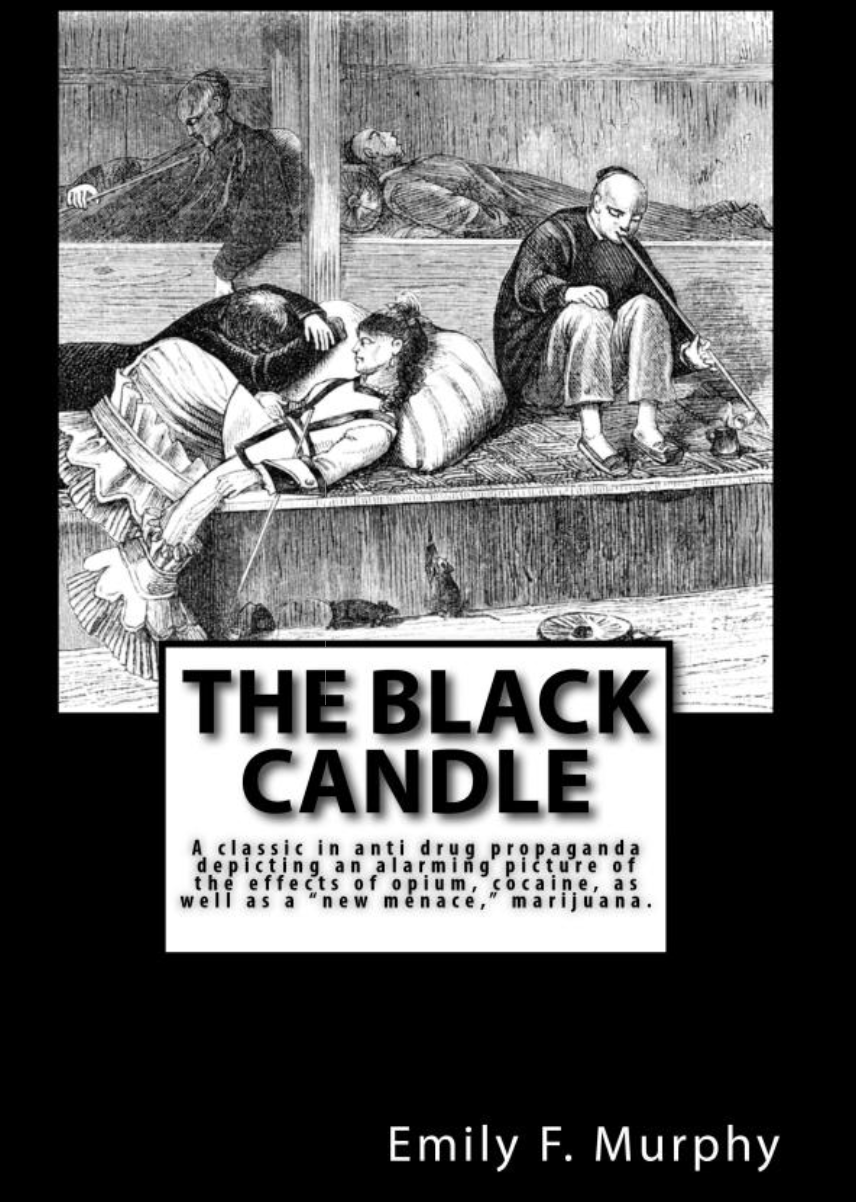

Women’s rights activist and jurist Emily Murphy further fanned the flames of race-related fury with articles she wrote for Maclean’s magazine that were compiled in the book, The Black Candle, published in 1922. Murphy linked “non-white men” to drug use and corrupting the white race, and depicted cannabis addicts as murderous maniacs.

“The Black Candle propagated a distinctly anti-Chinese sentiment that reinforced a sensationalist and racialized fear of non-white drug users. Murphy’s writings were situated in a moment in Canadian history that is defined by white supremacy and which formed the foundation for the racialized war on drugs we continue to live with today,” writes Jacqueline Kittel in an article for the University of Victoria’s The Arbutus Review.

At the time, cannabis was portrayed as a killer drug in the media — one that was just as, or even more, harmful than smoking opium or cocaine.

In 1923, cannabis was added to the Confidential Restricted List under the Narcotics Drug Act Amendment Bill with no debate or discourse about whether it was a dangerous drug.

Some critics have said that criminalizing cannabis was an attempt at tying the product to undesirable populations and had little to do with public welfare concerns.

“Canada wanted to position ourselves as a moral leader on this issue. We decided to add cannabis to schedule — not because of any indication of any problem — but to be proactive and to position ourselves as a leader,” Carstairs told HuffPost Canada.

Carstairs believes moral indignity tied to racial communities became the basis of the anti-drug movement.

“The effectiveness of the drug panic depended on the creation of a racial drama of drug use that featured ‘innocent’ white youth and shadowy Asian traffickers who turned them into morally depraved” dope fiends,” Carstairs says.

Reversing drug prohibition and legalizing cannabis is a historic feat. But as Boyd points out, before we turn the chapter, drug prohibition needs to be “understood as a social justice and human rights issue. The question is how will the government address the historic violence and injustice of drug prohibition?”

Comments are closed.