From Vice News link to article by Tom Keefer, Aug 3, 2017

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory is the Indigenous cannabis capital of Turtle Island. In this fiercely independent Mohawk community of 8,000 people on the Bay of Quinte, east of Belleville, Ontario, there are now over a dozen cannabis dispensaries, some selling purely recreational, some fully medical. Facilities range from trailers at the side of the road, to newly built multimillion dollar state of the art buildings.

With an estimated $30 million in sales in 2016, the growing cannabis industrydirectly and indirectly employs hundreds of people in constructing, growing, transporting, manufacturing, retailing, and providing security for Tyendinaga’s booming market in cannabis flower, edibles, oils, and topical salves.

Store owners report that the overwhelming majority of their clients are middle-aged non-Indigenous people, who are seeking alternatives to the opiate-based pharmaceutical industry in order to relieve their aches and pains.

No one should think that the Mohawks are Johnny-come-latelies to the cannabis industry. Cannabis has a long history among the Iroquois. Jacques Cartier noticed hemp species used by First Nations to make rope in the 1530s.* Along with giving Europeans the gift of tobacco and showing them how to smoke it, Indigenous people also taught Europeans to smoke the bud of the cannabis flower in joints or pipes.

With communities on both the US and Canadian sides of the border, Iroquois communities have long traded with each other. Not caring greatly for the arbitrary and illegitimate laws passed by foreigners illegally squatting in their lands, many Mohawks in Tyendinaga made good money running alcohol across frozen Lake Ontario during prohibition in the 20s and 30s.

And the cannabis industry was big back then too. A September 29, 1938 issue of the Montreal Gazette reported that Canadian police under the direction of Indian Affairs had been pulling up and burning “3,500 pounds of cannabis a day”—”a drug police fear more than any other narcotic”—in the Mohawk community of Caughnawaga (situated across the river from Montreal).

For their part, the Mohawks of Tyendinaga have what every industry emerging from prohibition wants: general tolerance verging on open acceptance, a safe and secure territory operating outside of official government jurisdiction, a taxation free zone, and easy access to urban markets and the country’s main transportation arteries.

Not dissimilar to the tobacco boom of 20 years ago, Indigenous cannabis entrepreneurs are rapidly advancing in an industry that is emerging from the shadows and looking for a place to land. Not only are the Mohawks becoming major players in the Ontario and Canadian cannabis industry, but Tyendinaga cannabis providers could be about to provide the biggest boost necessary for the reassertion of traditional leadership structures: an economic base for those seeking to live outside of the Canadian system.

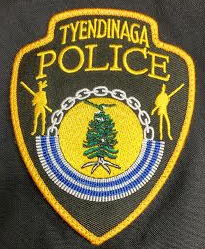

But earlier last month, the sovereign right of Mohawks to operate stores trading in cannabis on their own lands was challenged. On July 11, the Tyendinaga Band Council and the Tyendinaga Police (jointly funded by Band Council and the OPP) issued statements critical of the cannabis industry. On Monday July 17, Tyendinaga Police Chief Ron Maracle stopped in at Big Green’s dispensary wearing a firearm and told a meeting of store owners that they must immediately shut their doors due to his “public safety” concerns regarding the large number of dispensaries operating on the territory. He cited complaints in the community about increased traffic as well.

The conversation between Maracle and the dispensary owners was recorded and leaked to the press, and the discussion was widely heard around the community. Maracle’s intervention provided the encouragement the group of store owners needed to further coalesce. By the end of that night, the first official statement of the Kenhteke Cannabis Association had been adopted.

The statement declared in part, that “Cannabis is a healing plant and we are providing it as a medicine for people who need it. As Onkwehon:we people we have an intrinsic right to use natural medicines to heal ourselves, and an intrinsic responsibility to provide medicine to all those who need it. We will not tolerate the Tyendinaga Police or the Elected Band Council encroaching on our rights and responsibilities and trying to usurp the authority of our clans and decision making structures.” The statement was delivered to the Tyendinaga Police by a delegation the very next day.

With the police chief threatening to impose Canadian law upon a Mohawk jurisdiction in contravention to the symbolism of his department’s own badge, members of the Association called for a meeting of the Longhouse to discuss the cannabis issue.

With less than 48 hours notice, over 60 people attended the Longhouse meetingin late July. At the meeting, the issue of whether or not cannabis was a medicine appropriate for Indigenous people to use and share with others was “placed in the well” for discussion amongst clan families.

Through this action, dispensary owners indicated that they were willing to follow the jurisdiction and direction of their traditional governing system.

For his part, Maracle faced a serious backlash from all sectors of the community for disturbing an industry that has seemingly brought no harm and great benefits to the Tyendinaga Mohawk community.

With Maracle stymied by the quick and overwhelming community response to use a traditional decision making process to resolve the issue, questions still remain for the Tyendinaga cannabis industry—especially in terms of how traditional governance institutions could or should regulate the cannabis industry.

But as the dust settles from the latest altercation between band council police and traditional people, business continues to boom in what could be the freest cannabis jurisdiction in North America.

Comments are closed.