Fisherman Cody Caplin is self-representing in a court battle over Mi’kmaq fishing rights; six days of trial are scheduled in December.

CAMPBELLTON, NB – On October 12th, 2023, Mi’kmaw fisherman Copy Caplin appeared in court to fight an attempt by Crown prosecutor Denis Lavoie to summarily dismiss his constitutional challenge as “manifestly frivolous.” Caplin, a Mi’kmaw man from Ugpi’ganjig Eel River Bar First Nation, has been fighting charges under the Fisheries Act for exercising his Aboriginal and treaty rights to fish for food.

On September 12th, 2018, Caplin had his lobsters, boat, and trailer seized by the Federal government’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans while he was fishing in the unceded waters of Chaleur Bay. Prosecutor Lavoie’s motion would have ended the legal proceedings, and seen Caplin declared guilty and sentenced without any opportunity for the Aboriginal and treaty rights issues in his case to be heard.

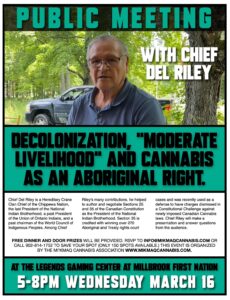

Caplin was assisted in the court proceedings by former National Chief Del Riley, the former president of the National Indian Brotherhood who negotiated the inclusions of protections for Aboriginal and treaty rights in Sections 25 and 35 of the Canadian constitution. In being recognized as Mr. Caplin’s agent, the judge explained that Chief Riley would not be able to present expert evidence in the trial, but would be able to sit at the bar and act as Mr. Caplin’s representative in court and to call and examine witnesses.

For whatever reason Crown prosecutor Dennis Lavoie was not in attendance at court to argue in favour of his motion, and was instead replaced by prosecutor Mark Stares, who quickly backed down from his predecessor’s attempt to dismiss the constitutional challenge. Referencing an October 2nd, 2023 letter from Mr. Caplin outlining his rights in reply to Mr. Lavoie, the Crown stated that it was withdrawing its attempt to dismiss the Constitutional challenge. That did not spare the Crown from a dressing down by Judge Donald LeBlanc who stated that he was “surprised by Mr. Lavoie calling Mr. Caplin’s constitutional claim as manifestly frivolous, and of being of little import.”

The judge added, “I looked it up in the dictionary and “manifestly frivolous” means that something ‘is readily perceived as frivolous.’ There must be another explanation. Frivolous would be a non-status person claiming that they have Aboriginal and treaty rights and making this claim.”

After laying into the Crown prosecutor, Judge LeBlanc considered a motion from Mr. Caplin’s former lawyer Liam Smith to dismiss the charges as the matters are “res judicata, having already been decided by the Supreme Court of Canada in favor of [the] Mi’kmaq, notably on September 17, 1999, in R v. Marshall.” The judge declined to dismiss the charges, saying that there were not yet “enough facts or evidence to accept Liam Smith’s plea to stay the proceedings.”

Stating that the “defendant has the right to defend himself, has the right to a day in court, has the right to have an agent to represent him, and has a right to proceed,” Judge LeBlanc established six dates in December to hear constitutional arguments. Those dates are November 30th, December 1st, and December 7-8, and December 14-15.

Caplin case about Mi’kmaw right to personal subsistence

Cody Caplin was charged with 10 different counts of violating Canada’s “Aboriginal Communal Fishing License Regulations” and thereby the Fisheries Act. Some of the charges relating to catching lobsters millimeters smaller than allowed by the regulations have been dropped, but others relating to not following Canada’s unconstitutional and unilaterally imposed fishing rules on Mi’kmaq people remain.

For example, Mr. Caplin is charged because he did “not affix a tag, float or buoy to each end of the fishing gear, contrary to s. 7 of the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations, SOR 93-332, thereby committing an offence punishable under paragraph 78a of the said Fisheries Act.”

Mr. Caplin is also charged with “possession of lobster” and “possession of lobster traps” without authorization from Canadian authorities. While Mr. Caplin was fishing under a number of licenses provided for by the regulations, he also deployed a number of traps to catch lobster to feed himself and his family without regard to the Canadian regulations.

Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences are regulations made by Canada’s Parliament that give the Federal Minister of Fisheries the discretion to issue a licence to an “Aboriginal organization,” which is primarily defined as an Indian Act Band Council – ie. a creation of the Federal Government under racist Indian Act legislation. “Interim Fishing Agreements” based on this licensing system were introduced after the Marshall decision established that Mi’kmaq people have a treaty right to “trade for necessaries” in the pursuit of a “moderate livelihood” to sustain themselves by hunting or fishing.

The 2019 “Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy Agreement” that Eel River Bar First Nation signed with the DFO provides funding to the First Nation to develop its fisheries, and Mr. Caplin is alleged to have violated the terms of this agreement by fishing outside of its regulations. However, the Agreement is very clear that “it does not, and is not intended to, define or extinguish any Aboriginal or treaty rights,” and that it is “without prejudice to the positions of the Parties with respect to Aboriginal or treaty rights.” The document further states that it “is not a land claims agreement or treaty within the meaning of Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and that it “does not affect any Aboriginal or treaty rights of any other Aboriginal group.”

This wording to ensure the Aboriginal and treaty rights are not negatively affected by the agreement was present in the first such agreement between the Band and DFO, which was made in 2001. Presumably, the importance of this section in the stems from the fact that the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences are granted unilaterally at the discretion of a Minister of the Crown, and thereby are a privilege that can be taken away, and thus not an inherent Aboriginal right. And while the Parliament of Canada has the jurisdiction within its own system to create and issue such licenses with “Aboriginal organizations such as Indian Act Band Councils, Mi’kmaq people also have their own inherent Aboriginal and treaty right to fish without such a license from the Federal government.

As the Marshall decision of Canada’s Supreme Court put it, “The accused caught and sold the eels to support himself and his wife. His treaty right to fish and trade for sustenance was exercisable only at the absolute discretion of the Minister. Accordingly, the close season and the imposition of a discretionary licencing system would, if enforced, interfere with the accused’s treaty right to fish for trading purposes, and the ban on sales would, if enforced, infringe his right to trade for sustenance. In the absence of any justification of the regulatory prohibitions, the accused is entitled to an acquittal.”

The same logic applies in Mr. Caplin’s case. When he was lobster fishing in the fall of 2018, Mr. Caplin was fishing a number of licenses for other people offered Communal Fishing Licences by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, as well as fishing for lobsters for his own personal consumption and sustenance. In so doing he was exercising his inherent, constitutionally protected Aboriginal and treaty rights under the Covenant Chain of Mi’kmaq peace and friendship treaties with the British Crown.

In R. v. Paul, 1980, a case where a Mi’kmaq man from Red Bank Indian Reserve was charged with the possession of undressed beaver skins off-reserve, the court outlined that the Treaty of 1725, the Treaty of 1752, the Treaty of 1779, Belcher’s Proclamation of 1762, and the Royal Proclamation of 1763 are the relevant treaties and proclamations that protect Mi’kmaq Aboriginal and treaty rights regarding hunting and fishing. Mr. Caplin’s defense will involve reference to all of these treaties and a variety of legal cases.

The Treaty of 1779 was made by Mr. Caplin’s ancestors from the Mi’kmaq district of Gespegeoag – and included Mi’kmaq people from Cape Tormentine to The Bay of Chaleur – Within the treaty, the Crown promised “That, the said Indians and their Constituents, shall remain in the Districts before mentioned, quiet and free from any molestation of any of His Majesty’s Troops, or other his good Subjects in their hunting and fishing.” As Judge Hughes of the New Brunswick Court of Appeal put it in R. v. Paul (1980) in reference to this clause in the treaty, “It could and probably should, in the circumstances, be interpreted as a recognition of a pre-existing right which the Indians had exercised from time immemorial and consequently may be treated as a confirmation of that right free from molestation by British troops and subjects.” As a result, the court allowed the appeal and set aside Paul’s conviction.

The Aboriginal and treaty rights described above, supersede the jurisdiction and authority of any other Canadian laws and regulations, as they are protected by Sections 25 and 35 of the Canadian Constitution, the highest law of the land. Section 52 of the Constitution states that, “The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of Canada, and any law that is inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution is, to the extent of the inconsistency, of no force or effect.” That should mean that the punishments provided for under paragraph 78 of the Fisheries Act, R.S.C. 1985 should not apply to Mr. Caplin, and that the charges against him should be dismissed.

Chief Riley, a long-standing Indigenous leader who has suffered over 9 years of racist oppression in residential and Indian day school, is looking forwards to the challenge of the court hearings and winning another victory for Aboriginal and treaty rights. “We fought to have our rights entrenched in the Canadian Constitution so that our people wouldn’t have to go through what Cody’s dealing with right now. It’s patently obvious that he has the Aboriginal and treaty right to fish to feed himself and his family without any license from the government, and we’re going to prove that once again.”

Contributions to Mr. Caplin’s court costs can be made by sending an e-transfer to cody.caplin@hotmail.com or by donating to the crowdfunding campaign at https://www.givesendgo.com/codycaplin.

Comments are closed.