Cannabis legalization was supposed to be a licence to print money. Three years on, nobody is turning a profit

From thewalrus.ca by Kieran Delamont August 5 2021

Back in 2018, during those months before Canada legalized recreational cannabis, things were good for the pot industry. Companies were being hyped as pioneers in “the green frontier” and “proof that money grows on trees.” Cannabis stocks were going ballistic, and three of the largest companies’ share values had each increased by more than 200 percent over the course of 2017—according to media outlet MJBizDaily, the Canadian Marijuana Index had risen by 117 percent in December of that year alone. Investors were not just making money, they were making money fast.

Never miss stories like this one. Sign up for our Sunday night newsletter: By checking this box I consent to the use of my information for emails from The Walrus.*Submit

Nowhere was the hype more obvious than Smiths Falls, Ontario, where a mundane press event one hot summer day in August 2018—the opening of cannabis producer Tweed’s visitors’ centre—offered a bizarre study of an industry primed for ascension. About a dozen TV cameras were present, plus photographers, reporters, dignitaries of the local business community, and politicians, all crowding through a routine facility tour. The event was a master class in buzz generation: it featured sample chocolates and an invitation to imagine them dosed with cannabis; production rooms that were still half empty and an invitation to imagine them finally full in a few short months; a gift shop and café and an invitation to imagine them packed with happy buyers. That all of it seemed somewhat half-finished could be glossed over—the promise of prosperity was obvious.

The town of Smiths Falls had come to see cannabis as a path to economic salvation. It had been hurting since 2008, when chocolatier Hershey closed shop. Tweed moving into the old chocolate plant in 2013 gave residents reasons both real and symbolic to be hopeful. As far as any of the company and government folks on the junket were concerned, Smiths Falls was ground zero for a new worldwide movement. The mayor called it the cannabis capital of the universe, and perhaps he was right. A few US states had piloted recreational cannabis, but this felt different—Canadian legalization would create a national industry with the sheen of a social revolution. Prohibition and the unequal criminalization of cannabis were, in principle, coming to an end. Global brands were in the making. Multinational corporations were on the rise. Countries across the world were going to look at Canada and be inspired—we were the future.

Three years later, much of that hype has vanished, and now both industry and government are beginning thorough post-mortems of what is, and isn’t, working with pot legalization. The lavish A-list parties, so common in the early days, were petering out even before COVID-19 arrived. Barely more than half of all pot sales today are conducted through the legal market (and that milestone was only recently reached). Back in early 2019, Tweed—later renamed Canopy Growth Corporation—had a valuation north of $20 billion and active growing facilities in St. John’s, Fredericton, Bowmanville, Edmonton, and Saskatchewan, as well as two in BC’s Lower Mainland. In the last year, all seven have been closed or sold. At the original location, in Smiths Falls, layoffs are a regular occurrence. Since 2018, total reported net losses amount to more than $3.8 billion. Across the industry as a whole, total losses since 2015 are north of $10 billion.

The most poignant sign of the failure of the cannabis business, however, might be sitting in warehouses across the country. At its peak, last October, following the 2020 growing season, there was about 1.1 billion grams of harvested or processed cannabis held in storage: 95 percent of inventory has not been purchased by retailers or wholesalers, and much of it is “assumed to be largely unsaleable,” writes MJBizDaily’s Matt Lamers, whether because of degradation or excess supply. We have more pot in this country than we can possibly sell. Producers today are sitting on a massive, and predictable, oversupply that is slowly becoming worthless—and that’s going to cost a lot of companies a lot of money.

THE INDUSTRY’S WOES can be traced in part to its temporarily lucrative early relationship with investment capital. After Justin Trudeau’s Liberals took power, in 2015, elected in part on the promise of pot, large producers, including Canopy Growth and Aurora, sought out listings on a variety of Canadian stock exchanges. They were after retail investors, and producers hired third-party investor-relations firms to promote their stocks as a once-in-a-generation chance to get in on the ground floor not just of a company but of an entire industry. Strong retail investment soothed whatever lingering anxieties Bay Street might have had about the sector. “The cannabis boom was an investment banker’s dream,” wrote Mark Rendell and Tim Kiladze in a 2019 Globe and Mail article. “With so much retail investor demand, it was easy to underwrite share sales—and to dictate the terms of the game.”

In the absence of any other metrics, like revenue or sales projections, investors learned to judge a company by “funded capacity,” a rough measure of how much cannabis a given company could potentially grow on the land it possessed. The result was a production arms race: more investment meant new facilities, which meant more production, which meant more investment, which meant more money pushed into production. This cycle went on and on.

“Cannabis investors asked for a big scale of production when they should have asked for a good scale of sales,” says John Fowler, the former CEO of The Supreme Cannabis Company, one of the producers that attracted a lot of buzz early on. (Supreme’s stock price doubled over the back half of 2017, and its market cap peaked in early 2018—nearly a full year before legal pot actually went on sale.) “They shouldn’t have talked about funding capacity, thrown money behind anybody who was going to build square footage.”

The logic governing the industry ahead of legalization tended to assume that any pot a company could grow would ultimately be sold. Licensed producers were accounting for their cannabis in ways that didn’t always make sense—valuing their inventory on their balance sheets similarly to stable commodities like vegetables, which have relatively consistent market prices and are more-or-less guaranteed to sell. (That many of the executives in the industry at that time had backgrounds in alcohol and commodities, where the price of a product and its path to market are more stable, likely played a role.) Really, cannabis had neither: nobody was exactly sure what the market price for retail pot would be, nor did anyone have a concrete idea of what consumers actually wanted. But pretending otherwise made the companies look great on paper. Valuation corresponded most with funded capacity, which is how you got a $20 billion company that hadn’t sold a single gram to recreational buyers. “Gross margins in the sector are distorted as a result, making firms look more profitable than they really are,” wrote Joe Castaldo in Maclean’s in early 2018, peeling back the layers of this accounting practice.

Producers themselves often did little to dispel this idea. Fowler recalls companies keeping and storing fan leaves (leaves that contain low levels of psychoactive cannabinoids) at a higher value than they were worth to bolster their balance sheets. “This was five years ago—nobody was asking questions. All the company has to do is say, ‘Well, we’re hopeful we’re going to find a way to make oil out of this, so let’s keep it on the balance sheet.’”

But, for investors who saw stock prices going gangbusters throughout 2017 and early 2018, the weed game was already profitable. The business model at that time didn’t demand actual weed sales: selling hype, selling the potential of selling weed, was proving lucrative. Stories of everyday Canadians getting rich on pot stocks fanned the flames even further. Investment was cast as a high-risk, huge-reward opportunity. Plus, it was providing massive amounts of capital to companies that needed to build highly specialized facilities to adhere to strict government regulations. With help from this investor enthusiasm, the industry expanded to 102 licensed producers by April 2018. The investments in facilities, massive hiring sprees, and fantastical marketing budgets all followed, undeterred by projections that it would be years before most producers turned any profit.

“There were steps along the way where decisions were made by big companies that . . . made sense at the time,” says Jay Rosenthal, a long-time industry analyst. “Public markets were responding to funded capacity. . . . The more capacity you had, the more people believed your company was going to be real and therefore would invest in your stock.”

Fowler makes a similar point. “It was advantageous for companies to keep that legend alive,” he says. “When the market was still giving people credit for so many years of forward sales, nobody wanted to stick up their hand and be a wet blanket and say, ‘Hey, we don’t think those sales are going to happen.’”

In the early days of legalization, product shortages, illustrated by news footage of lineups for stores with emptied shelves, reinforced the idea that more production capacity was needed. Under pressure to quickly supply the legal market and to stop wasting bureaucratic time, Health Canada adjusted its approval process to require that companies have a facility in place before they could be licensed. The idea was to bump serious players with existing assets to the front of the line and stop approving licences for facilities that were still speculative. By late 2019, the market had flipped into oversupply, but even then, little was done to slow the pace of production. The capitalist logic of the market had pushed large producers to make ever more cannabis—to strive tirelessly to outproduce their competition, to drive down production costs, and to flood the market with more and more pot products whether people wanted them or not.

LEGALIZATION HAS ALWAYS had critics from within the cannabis world, people who see a lost opportunity to support smaller, more sustainable producers as the bedrock of the cannabis industry. The know-how already existed in the many operations that had supplied unregulated markets for generations. Rather than constructing a hybrid system that legitimized parts of the existing cannabis market, the federal government set up a highly regulated system over which Health Canada maintained significant control. The result was an industry that was politically palatable but whose corporate character could feel alienating to some veterans of the cannabis world.

By the time legalization took effect, Tim Barnhart had already been selling weed commercially for a few years, beyond the reach of the Canadian government, out of his Legacy 420 store on Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, east of Toronto. He has watched the way cannabis legalization has played out from an Indigenous vantage: seeing corporations claim to be pioneering what he was already doing pretty sustainably for his own people.

Barnhart also saw some of these well-funded companies using their influence to impact regulations in selfish ways. In one memorable example, Canopy Growth’s former CEO, Bruce Linton, lobbied hard against outdoor growing, famously floating the theory to Senate members visiting the company’s facility that teenagers could ransack a licensed grower via drones.

“Had you had medical growers in there, and Indigenous Canadians, I think you would have had a set of good hybrid regulations, but what you have today is the financialization of [cannabis], and it’s not working for anybody—not even the LPs,” Barnhart says, referring to licensed producers.

There is a growing sense that things have not gone to plan. Since its high point in January 2018, the Canadian Marijuana Index has dropped by about 82 percent. There has also been turnover among many high-profile executives—Linton and Fowler, as well as leaders at Aphria and 48North, among them. The largest companies still rarely, if ever, report quarterly profits as an era of mergers and acquisitions begins to consolidate the market. The first half of 2021 saw Canopy Growth’s purchase of Supreme and the merger of Tilray and Aphria—two of the first and largest companies on the scene.

“Just as I don’t think any company in the industry would tell you they’ve gotten every decision right, nor should we expect that the federal government has gotten every decision right,” says Ryan Greer, former co-chair of the National Cannabis Working Group. The government is required to undertake a review of the Cannabis Act’s wider impact starting no later than this October, but the industry is getting a head start by leading its own analysis, highlighting issues like burdensome regulations and supply chain issues—or, as Greer summarizes, “general overall regulatory burden. It is a very costly and cumbersome process to navigate.”

Some now see an industry that has strayed from its original anti-prohibition path and failed in ways that feel distinctly capitalist. “There are people who aren’t able to fill their full prescriptions with legal cannabis because of costs,” says Caryma Sa’d, a lawyer and the executive director of cannabis-advocacy organization NORML Canada. A recent survey conducted by Abacus Data for Medical Cannabis Canada found that those who access medical cannabis legally pay on average 34 percent more for their medicine than if they bought from the unregulated market.

And yet, cannabis producers are throwing away more product than ever before. Since 2018, nearly 450 million grams of unpackaged cannabis have been destroyed, according to reporting from MJBizDaily. Nearly 280 million grams of that was from 2020 alone, representing almost 20 percent of all production that year. (An “expected” loss in commercial growing is between 5 and 8 percent.) Add to that nearly 3.8 million finished packages of dried flower, 1.5 million packages of extracts, and more than 700,000 packaged edibles.

“Maybe this is a feature of capitalism,” Sa’d says. “We are throwing out food while people go hungry; we have empty houses and people are homeless. So to see that replicated in the cannabis space is unfortunate but perhaps unsurprising.”

The question is not whether there is money to be made in cannabis—almost all experts agree that the pot business is viable in the long run—but why the industry’s most well-funded producers have been so consistently unable to turn a profit on something once talked about as a licence to print money. Canadians spent roughly $2.6 billion on legal cannabis in 2020—a healthy amount, but far short of the $6.5 billion that CIBC projected in 2018. Even in a year that saw legal cannabis finally comprise more than half the market, the biggest companies are still in the red: Aurora reported more than $3 billion in losses for 2020; Canopy Growth’s losses totalled $1.3 billion; Tilray lost $271 million (US). As Dan Sutton, CEO of the boutique producer Tantalus Labs, put it in an interview with BIV, “Today there are no consistently profitable cannabis cultivators—big or small—in Canada. Zero.”

WHILE THE FINANCIAL losses keep piling up, the industry is beginning to change. After a sluggish rollout, more “microcultivators” are gaining licences for smaller craft operations. A smaller scale of production could be a more sustainable business model, but even these seem ill-fitting within a heavily regulated cannabis economy. Forced, in most cases, to sell to a provincial wholesaler along with everyone else in the sector, craft producers can struggle to gain traction when they come up against the marketing departments of the Auroras and Canopies. The business model that underwrote the early days of legalization has yet to stabilize, and a long-expected phase of difficult bankruptcies, mergers, and consolidation—meaning mass layoffs and abandoned growing facilities—is here.

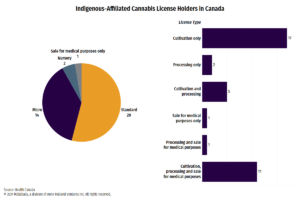

A drive through Tyendinaga or Kettle Point, Ontario, on the other hand, offers a window into another way forward: a sovereign, self-regulating Indigenous cannabis trade. Shops along the road are located just a few kilometres away from the field where the cannabis is grown. The quality is often quite good. Some of the shops are supported by Legacy 420’s nation-to-nation wholesale and quality-testing services. If nothing else, these operations demonstrate that safe cannabis sales aren’t the exclusive dominion of highly regulated shareholder capitalism—that safely growing and selling pot need not require a degree in capital finance.

“Done the right way, it can be a lucrative industry,” Barnhart says. “But Canada didn’t get it right. So now they have a costly product, a surplus that’s all dried out, and I don’t know what they’re going to do. There’s going to be huge corporate write-down again, and I’m not sure where that’s going to leave a lot of these players.”

The days of big corporate cannabis companies dominating the market may be on the wane, and a billion grams of weed they can’t sell could only accelerate that process. As Fowler says, turbulence at the major producers seems unavoidable for the foreseeable future—it could take two years to work through, it could take ten. “Unfortunately, the exuberance of the early days of our cannabis industry—we’ll live under that shadow for a long time.”

KIERAN DELAMONTKieran Delamont is a writer and photographer based in Nova Scotia, located in Mi’kma’ki—the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people. His work has appeared in Broadview, Maisonneuve, TVO, and elsewhere. He has been writing about the cannabis industry since 2016.BYRON EGGENSCHWILERByron Eggenschwiler has done artwork for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and GQ.

Comments are closed.