Lewis Mitchell believes his company can be a force for good for First Nations communities.

From vice.com link to article by Joshua Ostroff, Dec 6 2018

Eighty years ago, the police chief on the Caughnawaga reserve across the St. Lawrence river from Montreal spent weeks supervising the picking, carting, and burning of 3,500 pounds of pot under order of the Department of Indian Affairs. “The leaves and seeds of the marijuana plant contain a drug police fear more than any other narcotic,” ominously warned the Montreal Gazette on September 29, 1938, adding cops considered it a “greater menace” than opium and cocaine because it “often brings on insanity.”

This reefer believed to cause madness had reportedly been growing wild across the land now known as Kahnawake Mohawk Territory for “as long as residents can remember,” the Gazette wrote.

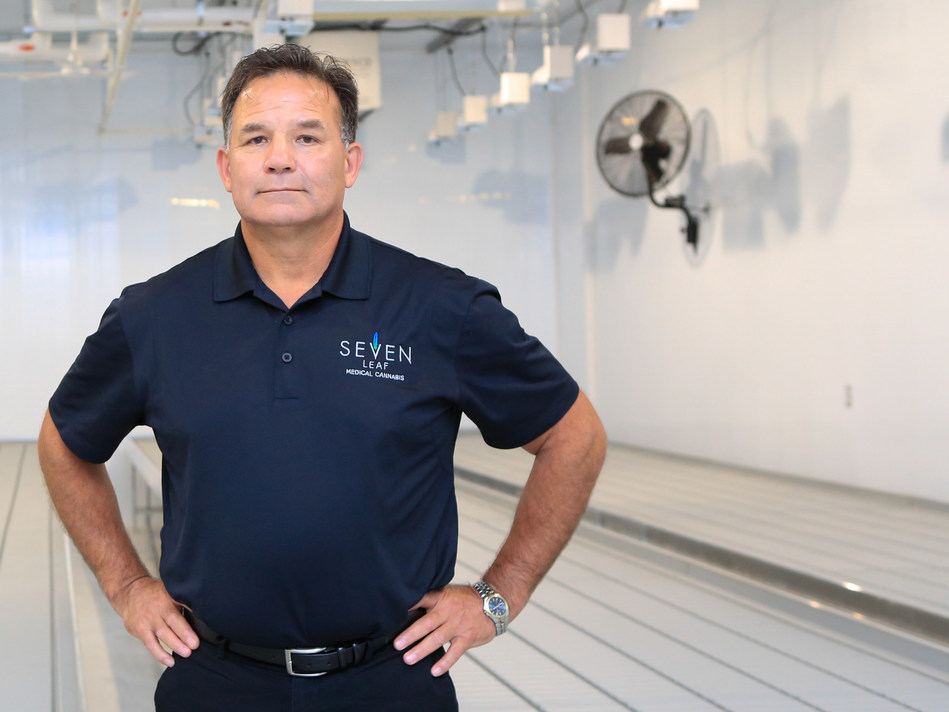

Fast forward to September 21, 2018—and a hundred klicks downriver to Cornwall Island in Akwesasne Mohawk Territory—and former police chief Lewis Mitchell was getting a far more preferable directive from the feds. After a four-year application process, his company Seven Leaf, had finally been given the go-ahead to cultivate cannabis. And Mitchell became president of Canada’s first Indigenous owned-and-operated licensed producer (LP).

“We’re pretty proud of that,” Mitchell told VICE. “To be the first is huge–and we’re looking to inspire not only our own community members, but hopefully other First Nation communities.”

Cannabis is no stranger to Akwesasne. Founded by families from Kahnawake in the mid-1700s, it straddles Ontario, Quebec, and New York state—a river-spanning a confluence of borders that’s made Akwesasne a locus for cross-border tobacco and weed smuggling.

A few days after Seven Leaf was licensed, Colin Stewart, an Elgin, Quebec resident nicknamed Cowboy, was sentenced to 11 years in a New York prison for smuggling in thousands of pounds of pot via Akwesasne. A decade ago, the 18-month cannabis investigation dubbed “Project Scarecrow” netted 230 charges against 19 people and $4.5 million worth of seized drugs. Most involved were from Ottawa but the weed went through Akwesasne to the States. Then there’s Jimmy Cournoyer, the Quebecois “Pot Playboy” who was arrested in 2012 for running a billion-dollar operation with Mafia and Mexican cartel links. Famously friends with Leonardo Dicaprio and UFC champ Georges St-Pierre, The New York Times called Cournoyer the “biggest pot dealer in New York City history” for smuggling over 100 tons of BC Bud.

Mitchell dealt with these crimes as a Mohawk police officer for 23 years, including a decade as police chief. In 2006, he expressed his frustration at anews conference following another bust: “We’re constantly getting black eyes for this type of behaviour. We have to remember it’s organized crime from Montreal, the big cities, coming into our community and exploiting our borders, exploiting our community.”

Mitchell retired two years later, and after the medical cannabis laws changed in 2013 to allow private licensed producers to grow and sell it, he started considering how a legal business could prevent that exploitation.

“It puts us on the right path,” he says of Seven Leaf. “It puts us on a path where those influences, the criminal organizations from the bigger areas, won’t have an impact in our community, where we don’t have to look over our shoulder. It’s an example we can set for other First Nations that there are regulations and controls that will help keep criminal elements out.”

Ironically, the biggest hurdle for Mitchell’s legal cannabis operation is what made it so attractive for illegal ones—the American border. The Seven Leaf facility is in Ontario, but the only way to access the Quebec side is by crossing into the U.S.

Even though New York plans to legalize recreational cannabis, it will still be illegal to cross back and forth with weed, because the drug is still banned by the U.S. feds.

“The geography of Akwesasne is very complicated,” Mitchell says. “We’ve done some work with U.S. Customs [and] developed a relationship even before we got our license.” He says they’ve met with a border representative and educated them on Seven Leaf and Canada’s cannabis regulations as well as their unique staffing situation, which includes vice-president and general counsel Lorraine White, a former Chief of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe (which is what Akwesasne is called on the U.S. side).

“They’ve actually given us the information that so long as our employees are truthful going across the border, then it shouldn’t be a problem for them to cross back and forth,” he says, though they obviously won’t be allowed to transport any cannabis. “Many live either in the Quebec portion of Akwesasne or in New York state, and they’ve got to go back and forth if they want to continue to work here.”

***

Mitchell was born and raised in Akwesasne. His entire family lives there. He went to local schools, got married, had kids and now grandkids. His wife owns a couple sporting goods stores, where Mitchell occasionally sells wooden lacrosse rackets that he carves for relaxation. He says his stance on cannabis began changing after medical-use was legalized in 2001.

“Growing up in this community with our people using plants for medicine–we have a long history of that,” he explains. “So when cannabis came along and I was educated on the medical benefits, to me it was just going from using one plant to another plant.”

While the stigma around cannabis use remains, he says, “I’m seeing more and more of our elders, and even some of our medicine people, looking at using it in those terms.”

Though concerns and accusations of hypocrisy have been raised about police profiting off the legal cannabis industry,Mitchell says his former job was what won support for his project given Akwesasne’s history.

“When I spoke to the elders, they were glad I was doing it. They knew that I wouldn’t be bringing something that would harm the community [because] I spent most of my adult life protecting the community. There was a level of trust that nothing is going to be leaking out the back door, everything’s going to be accounted for. It’s going to make this venture safe for our community and a benefit to our community.”

While Mitchell admits to some ex-cop backlash for embracing an industry he once criminalized—”I’ll get a little bit of it, but I don’t get a lot”—mostly, he says, people ask him about jobs.

Seven Leaf is located in the former Iroquois Water bottling plant that closed in 2006. Like Canopy Growth’s takeover of the old Hershey’s chocolate factory in nearby Smiths Falls, Seven Leaf started retrofitting the 84,000 square feet space in late 2014.

“Oh man, that’s huge for us. They just couldn’t make a go of it, for whatever reason. Until we came in here this building sat vacant, and it’s a big building. At maximum capacity, we expect to hire 75 people from our community. Presently we’ve got 31 community members preparing for our first crop to be harvested. So there’s a lot of opportunity.” That is vital to Akwesasne where, Mitchell says, “underemployed” young people with degrees are often stuck in menial jobs. “They could do more.”

Seven Leaf is finally getting ready to grow, and plans to have products available next spring. By Fall 2019, when they’ve tripled production capacity and fully staffed-up, they’ll be paying out $3.6 million in salaries which will also be a stimulus for other small businesses, Mitchell says.

“Hopefully that money turns around a few times within our own community before it leaves,“ he says, noting they’ll probably be the biggest private business on the Canadian side. The other major one is the Mohawk casino in the U.S., and Seven Leaf wants to prove cannabis can be a similar Indigenous economic driver here.

Mitchell says other First Nation governments have been contacting him regularly for advice, potential partnerships and site tours—and he wants for Seven Leaf to someday become a training facility. “They’re feeling left out, that they weren’t consulted, and they want to get into the industry. So there’s a lot of discussion going on. It can be another revenue source for First Nation governments,” he says, so needs like clean water and education won’t depend on federal funding.

But time is running out. “If they wait five years down the road,” Mitchell says, “it could pass them by.”

Comments are closed.