From The Baltimore Banner by Clara Longo July 1 2023

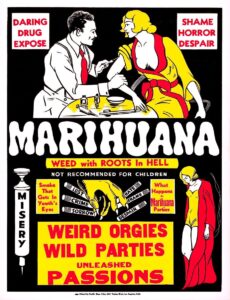

In the summer of 1924, Baltimoreans woke up to an illustration of a devil in their flagship newspaper. The demon, the diablo, rose among the fumes of cannabis cooking in a pot over a bed of coals.

The smoke drove the “victims of habit,” who usually shut themselves up in a tightly closed room, “into a frenzy.” The “Mystery of the Strange Mexican Weed,” read the headline of that August edition of The Baltimore Sun, one of many news outlets at the time to use such imagery and language.

“All the vicious tendencies in the makeup of humans are brought to the fore by indulgence in the dread marihuana weed that grows in Mexico,” the article went on.

The illustration reflected the anti-Mexican sentiment spreading across the country, often disguised as a call for the prohibition of a “dangerous” drug.

As Maryland on Saturday joins 22 other states and the District of Columbia in legalizing recreational adult use of the drug, state leaders also considered the debate about what to call the drug. In the past, marijuana and cannabis have been used interchangeably.

But the stigmatization of the word marijuana, scholars said, has had such a long-lasting, often harmful effect on how people perceive the plant — particularly in Mexican families and among broader Latino communities — that some people consider the word racist.

Maryland lawmakers opted to use the word “cannabis” in the statute that decriminalizes the drug, said Madelin Martinez, executive director of the Maryland Legislative Latino Caucus, but, unlike in Washington, there was no explicit effort to strike the term “marijuana.”

The priority was to ensure that the legislation would reduce the number of Black and Latino people incarcerated for possession of the drug, Martinez said.

Moving forward, the state is working to educate Latinos through workshops on what legalization means and opportunities in the cannabis business, hoping that it will prevent misinformation.

“At least when when they hear it from us and what it [the legalization] means, what the legislation does and how it will also ensure that our communities are not targeted,” Martinez said. “Maybe that would help a little bit with the stigma.”

When Antonio Valdez hears the word “marijuana,” he cringes. He can see his mother eyeing him sternly, holding a chancla, a flip-flop used to deliver discipline in many Latin households.

“You could reach the pinnacle of your career,” he said. He could have, say, attended Harvard and became an astronaut. He could go to the moon and bring back a moon rock for his mother.

“Ah, pero fumó marijuana,” she would say, meaning “but you smoked marijuana.”

For a long time, using cannabis was somewhat of a scarlet letter in Latin households. “That is the culture, that’s the role of shame,” he added.

A recent study by the National Hispanic Cannabis Council on cannabis awareness and perception among U.S. Hispanic people found that parents are the primary cause for feelings of shame over the drug, he added. The study, which queried more than 1,000 people of Latin descent of varying ages, gender, incomes and levels of acculturation and education found that, largely, Latinos are fine with the drug and use it recreationally or medicinally.

“Latinos’ tolerance and acceptance of cannabis is higher than what we thought,” said Valdez, the executive director for the council.

More surprising to Valdez is that 41% of the respondents are more comfortable with the word “marijuana” over cannabis, while 41% have no preference either way.

He said aspiring entrepreneurs should cater to their audience. There could be some power in marketing their product as “marijuana” if prospective customers lean more toward that name over others.

“Society wants to lump us [the Latino community] as a homogeneous society because of our language,” said Valdez, who has long studied the community as an untapped market. “And that is so incorrect.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/baltimorebanner/IYXO3E5ZXJGHVDKM7CTHR67UPQ.jpg)

Santiago Guerra, a professor of Southwest studies at Colorado College, said using culturally-specific and significant terms for the plant can make the cannabis industry more inclusive. And, he adds, using the word “marijuana” means recognizing the buried history of the relationship of the indigenous Mexican population to the plant.

Mexican newspapers used the word “marihuana” to describe the plant as early as the 19th century. Indigenous Mexican people developed and popularized the smoking of marijuana cigarettes, using the plant medicinally and as a intoxicant, after Spanish colonizers introduced it into the continent in the 15th and 16th centuries. The plant likely came from the border of Pakistan and China, gradually moved into the Middle East and up the Iberian Peninsula, until enslaved indigenous people were forced to grow hemp in present-day Mexico.

Guerra said the view that the word marijuana is racist is rooted in a serious misunderstanding of the prohibition of the plant. What fueled the U.S. criminalization of the plant was anti-Mexican sentiment that surged after the Mexican-American War in the 19th century, he said, when the federal government had to deal with a new racialized population in the Southwest that was largely indigenous.

In republishing the devil illustration and story in 1997, The Sun acknowledged the article used stereotypes against Mexicans to “create hysteria” over the plant and “gave misinformation over the drug effects.” Along with the devil were illustrations and photos of men depicted in racist stereotypes, wearing hats with large brims and pulling donkeys through farm fields.

Valdez and Guerra said such language and images were typical, and used as a tool to demonize and alienate the Mexican population.

As states began to legalize cannabis in what Guerra calls a “psychedelic renaissance,” he said there must be an acknowledgement that the reason we have this relationship with cannabis — with marijuana — is due to Mexico.

“That history gets silenced by saying ‘Don’t use that word because it’s a racist term’,” he said.

Comments are closed.