The Indigenous owners of an unlicenced medical-marijuana dispensary in Stratford say they have the constitutional right to operate without jumping through provincial and local regulatory hoops.

By Galen Simmons | Jun 24, 2023

Despite concerns from police and neighbours, the Indigenous owners of an unlicensed medical-marijuana dispensary say they have the constitutional right to operate in Stratford without jumping through provincial and local regulatory hoops.

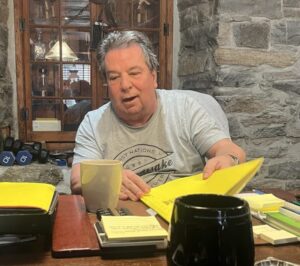

Prior to opening Organic Solutions Dispensary at the beginning of June, owners Tom Jackson, an Anishinaabe man from the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation, and Kirk Marquette, an Indigenous man who was born and raised in Stratford, say they delivered official notice of their business to Mayor Martin Ritsma and Stratford police via a letter written by Del Riley, the former chief of the assembly of First Nations.

In that letter, Riley, a hereditary Crane Clan chief of the Chippewa Nation, indicated that Organic Solutions would operate as a member of the North Shore Anishinabek Cannabis Association, an organization that advocates on behalf of the growing number of self-regulated, Indigenous-owned cannabis growers and sellers popping up across Canada.

A few days later, Marquette and Jackson recorded a visit by Stratford police officers to their shop at the corner of Monteith Avenue and Lorne Avenue West. In the video, the officers informed the two owners they were not permitted to operate a marijuana dispensary without first obtaining the proper licences through the province and the city.

“We’re using our Charter of Rights to do it,” Marquette said. “The Stratford cops come and bullied us, telling me this part of Monteith Avenue isn’t traditional land. The people across the street can sell flowers. Why can’t I sell flowers? My flowers are no different than their flowers. … Then they come after us with, ‘Well you need a business licence. You need this from Health Canada. You need this.’”

Jackson, who operated another dispensary on the Kettle and Stony Point First Nation reserve for almost five years, said the Stratford was offering “affordable medicine.”

“I was a medical patient myself. That was one of the reasons I got into this. I couldn’t afford to pay $11 a gram straight up. I was prescribed a 90-gram prescription per month, and I couldn’t afford to meet those needs. That’s over $1,000 a month … (to treat) post-traumatic stress. It was also an exit drug or a harm-reduction drug. I was into other drugs growing up and it kind of helped to ease that and take away my urges to use hard drugs.” he said.

At this week’s Stratford police services board meeting, police Chief Greg Skinner told members his department had received two complaints from area residents concerned with additional traffic generated by the dispensary, potential safety risks associated with the sale of cannabis to underage people, and customers of Organic Solutions smoking marijuana in their vehicles before driving off the property.

“There have been a number of municipalities where similar trading posts (selling) medical marijuana … on unceded territories without proper business licensing have popped up,” Skinner said. “London, Ottawa, Toronto and Stratford are the four that I’m aware of. … We’ve been working with bylaw to research the presence of this particular trading post in the City of Stratford. We’ve also consulted with the Crown (attorney) to get a legal opinion as to what if anything we should be doing from an enforcement perspective.

“We’re still waiting for that response from the Crown. … We are continuing to monitor this situation. We are going to continue to document what’s going on there, and we are going to await direction from our legal support to see what our next steps will be. I can tell you to the best of my knowledge, in Ottawa, Toronto and London they have not taken any enforcement action.”

Addressing the concerns raised at the meeting, Marquette and Jackson said their business follows strict safety rules set out by the North Shore Anishinabek Cannabis Association. These rules includin checking the identification of customers to ensure they’re of legal age to purchase cannabis and prohibiting the smoking of marijuana by customers on the property. Marquette did acknowledge he uses medical marijuana on the property during the work day to manage pain still suffered as a result of a motorcycle collision, as well as pain from a previous back injury.

“It is safe and we are taking into account the neighbours,” Jackson said. “Respecting our neighbours and (not) having people hanging around is something we take seriously. We can’t be serving people cannabis and then they get in their car and they drive away after smoking on the premises. And we have no qualms about having a dialogue with anyone in the community. We’re open to that.

“We didn’t come here and open overnight behind closed doors. That was why we served (notice) accordingly and did everything above board.”

Riley, who is serving as a spokesperson for many of these unlicensed dispensaries, said Indigenous people have constitutional and treaty protections that allow them to operate businesses on traditional land.

“They have the right,” he said. “In our time throughout history, a lot of this has been confused because Canada’s had this racist Indian Act in place against the First Nations People. … First of all, Britain really didn’t have the money to buy the lands from First Nations. The process that set up all the treaty making was the Royal Proclamation of 1763 … (which says) if they want possession of it, they have to buy it from the First Nations. … But none of that happened and if you go look at your registry office, you’ll find there’s no purchase from the Indians.

“There’s another Royal Proclamation that comes into place called the Rowan Proclamation in 1854. … It essentially was a protective measure by Britain at the time to make sure the Indians weren’t removed from the lands they were on because there were no real treaties at the time. … Because it was a Royal Proclamation, it’s protected by the constitution as well,” Riley added.

That proclamation, Riley explained, recognizes Indigenous rights to sell goods on traditional lands. While Riley affirms that right is protected under the constitution, he suggested Indigenous people haven’t been able to fully exercise it because many didn’t understand how it could be applied.

“Nobody was around to interpret all of this for them. … There’s an attempt out there to … try to bring Indians out of the extreme poverty they’re in, especially in the northern areas. … I don’t think anybody should really be scared (of these businesses) because, in most cases, the money will probably be spent in those towns anyway. (Their) licence (to sell cannabis) is really a constitutional one. … It fits right in with this new philosophy of the government called reconciliation,” Riley said.

Both Jackson and Marquette say the opportunity to break out of that cycle of poverty by owning and operating a medical-marijuana dispensary on land that once belonged to their people has been life changing.

“It’s changed my life drastically in what I can do in regards to helping my family, helping my siblings,” Jackson said. “I’ve not been able to participate in normal economic things, never mind cannabis, being raised on a reserve and being second pick to everything. I’m all about telling people in my community to leave the reserve, to go out into the cities and start working there.

“There’s a mentality down there of us and them, so the young people don’t realize there’s a whole world out there.”

Be First to Comment