By BRENNAN DOHERTY StarMetro Calgary Mon., Nov. 19, 2018

CALGARY—Cashing in on the “green wave” of Canada’s recreational cannabis industry is as much a question of sovereignty as it is profit for some First Nations communities and entrepreneurs.

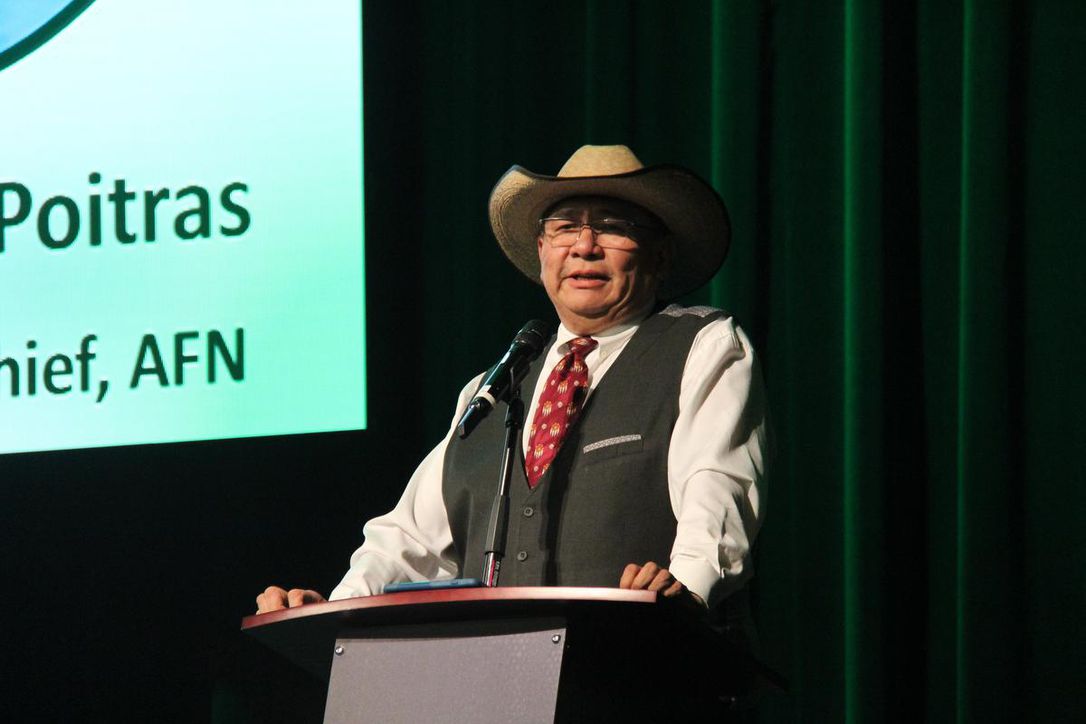

Roughly a month after the Canadian government legalized recreational cannabis, hundreds of delegates filled the Tsuut’ina Nation’s Grey Eagle Resort and Casino’s event centre for the National Indigenous Cannabis and Hemp Conference, a three-day event on what the cannabis industry means for First Nations communities across the country.

“We are all stakeholders here,” said Chief Lee Crowchild of the Tsuut’ina Nation in an address to the conference Monday morning. “And I believe we have to step out of the mindset that was imposed upon us and really set the future direction.”

Getting in on Canada’s multibillion-dollar cannabis industry — and the rewards it could reap — is a major incentive for First Nations communities. The hosting Tsuut’ina Nation is one of them: Chief Crowchild confirmed in July that the First Nation’s council was in talks with the cannabis industry.

Many First Nations communities struggle to afford basic necessities, such as clean drinking water or adequate health-care facilities, and some of them see the cannabis industry as a potential avenue for economic self-sufficiency. How exactly this should work varies by the First Nations communities and entrepreneurs looking to take part.

For some, getting into the cannabis industry represents a chance to assert their economic and political sovereignty. The Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne — which straddles the borders of Ontario, Quebec, and New York state — took this approach. It established its own interim cannabis licensing and consumption bylaws before either province did and doesn’t believe either one should get involved in regulating the community.

“This is an exercise of our sovereignty — our ability to actually generate a financial revenue stream independent of the federal and provincial governments,” said Lorraine White, vice-president, general counsel and the head of governmental relations for Seven Leaf.

The company says it is the only wholly Indigenous owned licensed producer in the country. By the time Seven Leaf is at operational capacity, it expects to employ around 75 people and institute a policy of giving back to the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne — in the form of funding for community programs, salaries for its employees, and revenue for the region. It also intends on strengthening its own bonds with First Nations producers and communities from coast to coast. In short, it wants to establish more than just a for-profit company within a First Nations community.

“We want to have a First Nations business model,” White said.

But other First Nations entrepreneurs are avoiding the political fight altogether.

Wesley Sam isn’t doing so from lack of experience. He’s spent decades in politics as a councillor and chief of the Burns Lake Band in British Columbia, and also served as a municipal councillor and acting mayor for the village of Burns Lake. Now, he’s the founder and executive chairman of Nations Cannabis, a B.C.-based cannabis production company, and said the political fight is going to take far too long.

“First Nations can’t wait for politics to spin its iron wheels,” he said. “Because the market is not getting bigger. It’s shrinking by the day. We need to get into the market right now to have our market share.”

Burns Lake is also facing an impending economic problem. The B.C. municipality and many of those around it are very reliant on the province’s forestry industry. But the area’s annual allowable cut — a cap on the number of trees that can be cut per year — is due to drop by as much as 70 per cent in the next two years, Sam said. Beetle infestations in the area have also proved to be a huge problem. Without these resources, First Nations and non-First Nations communities alike in the area are losing jobs.

“This is why First Nations are demanding to be a part of this green rush, as they call it,” Sam said.

Nations Cannabis isn’t based within a First Nations community. Instead, its 50,000-square-foot production facility — in a former forestry industry building — is on a piece of land owned by six First Nations in the area. Each benefits from the company’s efforts, and also receives 5 per cent of Nations Cannabis’ earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization to go toward whatever social or infrastructure projects their communities need. One of their proposed plans is to help fund a medical centre.

“We won’t set the priorities. They’ll set the priorities,” said Marc Storms, Nations Cannabis co-founder and chief marketing officer.

But regardless of how First Nations decide to handle the cannabis industry’s investment in their communities, there is a desire to go about it in a way that respects the local traditions and customs of whichever communities decide to take part. Chief Crowchild said during his address that the economic benefits aren’t necessarily the only important part of the discussion for First Nations. There are medical and ethical dimensions, the sovereignty discussion — and how cannabis benefits First Nations peoples.

“We’ve got to keep everything in balance here,” he said.

Comments are closed.