ONEIDA — Recreational cannabis is being legalized in just two week, but illegal pot shops keep popping up in Ontario Indigenous communities, including one shop near London linked to a former band chief.

The explosion of illegal marijuana dispensaries is a divisive issue in aboriginal communities. Operators say the outlets, whose customers drive in from nearby cities and towns, bring needed jobs to their communities.

But critics, including the chief of the same Southwestern Ontario community where the former chief works at a pot shop, say the businesses shouldn’t be allowed to operate unregulated.

And with Ontario warning any illegal operators won’t get a crack at becoming legal retailers, the growth in outlets defying the law still looms large even with recreational marijuana use becoming legal in Canada on Oct. 17.

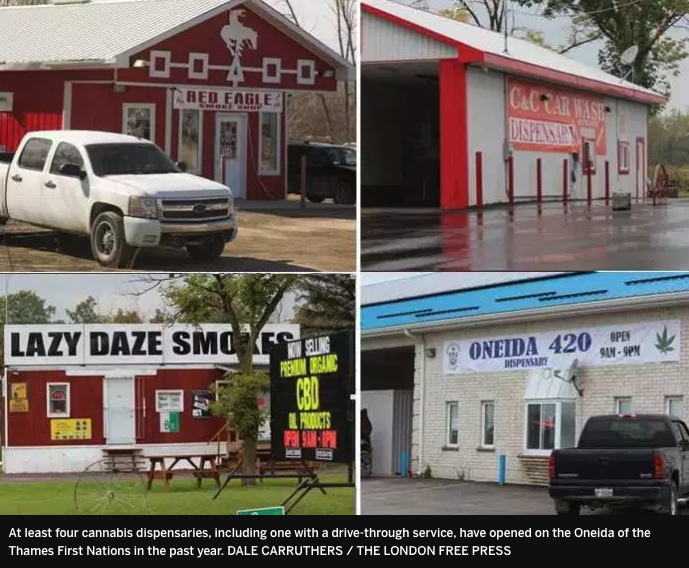

A 30-minute drive southwest of London, four dispensaries have set up shop in recent months on the Oneida of the Thames First Nation, a small community of little more than 2,100 people.

Police have fought similar illegal operators in cities across Ontario in whack-a-mole style raids, shutting them down only to see them return, but the crackdowns has trailed off as legal cannabis use nears.

In aboriginal communities, however, authorities have largely turned a blind eye to the unsanctioned shops.

Oneida Chief Jessica Hill denounces the outlets for opening without consulting band officials and promoting the use of an illegal drug.

“There is no accountability to the community at all for what they’re doing, and the community is against drugs,” Hill said. “Also, it brings in all types of people that have never come here before. Now (they) come here looking for drugs.”

Located beside a Canada Post office, Oneida 420, the newest dispensary, is staffed by former three-term Oneida band chief Randall Phillips.

Phillips, whose latest two-year term ended in June, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Grand Chief Joel Abram of the London-based Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians (AIAI), an umbrella group that fights for member bands’ treaty rights, compares the dispensary-opening frenzy to smoke shacks selling black market cigarettes.

Since the 1990s, Ontario’s more than 130 First Nations communities have been havens for selling contraband tobacco in the province, where more than one-third of all smokes are now bought illegally.

“People look at it as a source of income,” said Abram, whose organization represents seven First Nations, including Oneida and two others in Southwestern Ontario.

But support for the marijuana retailers isn’t consistent, he added.

“It varies from community to community. Some communities don’t want it at all, some are interested in the economic aspect of it,” Abram said.

“But everybody, we’re all concerned about the mental health aspect, especially when it comes to youth, and that’s where we’re pressing for resources.”

Cracking down on dispensaries is a complicated issue, Abram said, noting Indigenous police are underfunded.

The Ontario Provincial Police, who work with Indigenous police, say they’ll take a consistent enforcement approach to manage the issues relating to illegal cannabis storefronts.

“Once the new provincial laws and regulations are finalized and reviewed, the OPP will adjust our enforcement strategies accordingly,” Staff Sgt. Carolle Dionne said in an email.

The uptick of dispensaries isn’t unique to Oneida. On the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, east of Belleville, more than 30 marijuana retailers operate in defiance of the law.

Tyendinaga dispensary owner Jamie Kunkel, whose Smoke Signals franchise now operates in three provinces, says the businesses have been a boon for the community.

“At this point, it’s beneficial to every part of the territory now,” said Kunkel, adding that pot shop owners use proceeds to sponsor sports teams, fund local improvement projects and make community donations.

Kunkel organized the Indigenous Cannabis Cup, an event that drew 60 vendors and thousands of attendees to Tyendinaga over the Victoria Day long weekend. The event’s success – and the spread of dispensaries – shows the Indigenous appetite to get involved in Canada’s cannabis industry, Kunkel said.

“At the end of the day, we have a right to an economy and to operate within the economy,” he said.

But under Ontario law, recreational marijuana will be legally sold to residents over the age of 19 only through a government-run delivery service when the drug is legalized.

The province hasn’t started the application process for bricks-and-mortar dispensaries, which won’t open until April 1, 2019.

Any illegal operators still selling pot after Oct. 17 won’t be eligible to apply for a retail licence under new Ontario legislation, its Tory government says.

Some Indigenous pot shop operators, like Kunkel, say they’re not interested in applying to be an approved retailer.

“Right now for us, I don’t see it being an option,” he said, adding he doesn’t anticipate police cracking down on Indigenous-run dispensaries after legalization.

“We’re here. We’re not going anywhere.”

dcarruthers@postmedia.com

twitter.com/DaleatLFPress

Comments are closed.