From Vice News link to article by Rachel Browne, Jun 1, 2017

Scanning through images of the top brass at Canada’s legal medical cannabis industry reveals a sea of white.

Almost all 45 of the federally licensed producers (LPs) are run by white men. They’re currently the only businesses legally allowed to cultivate and sell the product, and only for those with medical prescriptions. And they’re the companies that will continue to lead the recreational market, which the government plans to implement by next year.

“If we’re looking at the medical model as our crystal ball for what’s in store, the green rush has been pretty whitewashed.”

VICE News asked every LP for detailed diversity information about their executive boards and senior management, and any inclusion initiatives currently in place. Of the companies that responded, representing 20 LPs, two said their executives include people from visible minorities, for a total of six people. Others pointed to their senior management teams, some of which comprise more than 50 percent women.

Inside Bedrocan, a licensed producer in Scarborough, Ontario.

The overrepresentation of white leadership is not exclusive to the cannabis business world, although Canadian statistics on the issue in general are scant. A 2016 report on corporate governance found that things have been improving in the country in recent years, with almost three in five organizations including a member of a visible minority on their boards, a 20 percent jump from 2015.

But the weed business is different because it has its roots in an illicit market, one targeted by laws that have been disproportionately applied to people of colour and minorities. For those fighting for equal opportunities in the future legal regime, the lack of diversity at the helm shows how corporate and government structures continue to favour a privileged few.

“In Canada we have, as in the United States, a fairly stark racial disparity in cannabis arrest rates.”

“If we’re looking at the medical model as our crystal ball for what’s in store, the green rush has been pretty whitewashed,” said Jenna Valleriani, who researches addiction at the University of Toronto and also advises the Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy. Valleriani, who researched Canadian cannabis companies for her doctoral thesis, is disappointed that the country’s policymakers aren’t talking about how to bring those who have worked in the illegal cannabis markets into the regulated fold.

At a time when the industry is at a crossroads, she and other drug policy experts are calling on the government, and cannabis companies themselves, to pursue measures that seek to repair the harms caused by drug prohibitions, which have long been criticized for having racist outcomes.

While most of the licensed producers who responded to VICE News spoke in broad terms about boosting diversity in the workplace, none provided written company policy to that effect. Although Aurora said it had begun developing an LGBTQ2+ Committee.

Only DelShen Therapeutics Corp. reported having a “community benefits agreement” with First Nations partners. Its cultivation facility is located within the traditional territory of the Wahgoshig First Nation, a spokesperson said, who added that the First Nation has made a “substantial investment in the company.” And as part of the partnership, DelShen said it’s working with the community to fund a drug and alcohol prevention and treatment program within the First Nation.

Plants at Bedrocan Cannabis Corp..

No LP mentioned efforts to work with those who have been criminalized by cannabis laws in the past — and key individuals of the LP, including its officers and directors, must undergo an extensive security clearance involving a criminal background check in order to pass Health Canada’s application process. Only Tilray, one of the biggest players in the industry, confronted this.

“We recognize that the prohibition has disproportionately harmed diverse people and communities,” a Tilray spokesperson wrote in an email. “The industry as a whole has a lot of work to do in attracting, retaining and promoting leaders from diverse communities and backgrounds.”

Data

While statistics on the ethnicity of those charged and convicted of crimes in Canada is not readily available, government reporting shows that black and Indigenous offenders are overrepresented in prison populations across the country. And researchers have uncovered new data that shows how the law has disproportionately affected minorities when it comes to cannabis-related crimes.

“In Canada we have, as in the United States, a fairly stark racial disparity in cannabis arrest rates,” said Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, a sociologist at U of T who has reviewed embargoed data on people in Canada who have been charged and convicted of cannabis crimes. He can’t describe it in great detail at the moment, but said it will be released at a later date, and will shed light on the issue for the first time.

“The unreleased data I’ve examined, going back at least a decade, shows that black and brown people in this country have been disproportionately targeted by cannabis prohibition,” explained Owusu-Bempah, who has been vocal about the effects of drug criminalization on youth and disenfranchised minorities.

Issuing pardons to people with minor cannabis-related criminal records would be a welcome measure.

The most recent numbers from Statistics Canada, which are not broken down by race, show that more than 19,000 adults in Canada were charged with cannabis possession in 2015, down slightly from 21,629 the year before.

And for those looking to get into Canada’s legal market, Owusu-Bempah said the exorbitant costs of getting a federal license from Health Canada, coupled with the barriers those with criminal records face when applying for a job, means the system favours the wealthy elite. Currently, CEOs and top management must undergo extensive criminal record and security background checks by law enforcement as part of Health Canada’s application process to become a licensed producer. And even though it’s not a government requirement that all LP employees have clean records, most companies impose that on everyone who works there to avoid risks.

“If people with criminal records aren’t allowed to participate, then that’s going to exclude a large number of people, especially those who were impacted by racist policing and racist laws,” said Owusu-Bempah.

Issuing pardons to people with minor cannabis-related criminal records would be a welcome measure, he continued. The Liberals have signaled they might be open to the idea of blanket pardons after the recreational system comes into effect, but have refused to decriminalize pot in the meantime or call for an amnesty on new possession charges.

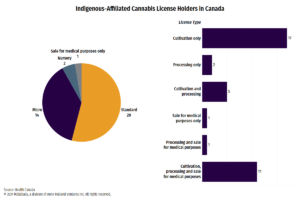

Oakland

The federal government’s recreational cannabis task force — composed of mostly white people — recommended supporting small producers and “the opportunity for Indigenous governments or individuals to acquire cannabis production and distribution licenses,” both of which have been praised by legal and cannabis communities. However, the force’s final report released last December did not discuss how to deal with those with cannabis-related criminal records or improving diversity of staff within the licensed producers. (It did acknowledge that people with criminal records “may have difficulty finding employment and housing…”)

But there are a number of initiatives in the U.S. that Canada can look to when it comes bridging the illegal and legal cannabis industries, particularly in Oakland, California.

“The customer base that you’re serving should look like your management team and if it doesn’t, then there’s a problem.”

After California legalized recreational cannabis last year, the Oakland city council took the unprecedented step of proposing an “equity permit program” for cannabis businesses to help address the fact that black people make up 77 percent of those arrested for cannabis crimes in the city, and 15 percent were Hispanic. Under this program, those who have been jailed for pot-related crimes over the last decade are first in line for new medical cannabis business licenses. What’s more, those who are granted the equity permits are eligible for interest-free business loans and other assistance. The permits may also be granted to those living in communities that have seen 150 or more cannabis arrests in recent years. The program was approved by city council unanimously this month.

Employees at Bedrocan Cannabis Corp..

It’s this sort of initiative that Valleriani would like to see happen in the leadup to legalization in Canada. “There seems like this ongoing glaring gap that nobody is talking about from a policy standpoint,” she said. “You can’t have best parts of legalization without addressing the problems under prohibition.”

When VICE Canada asked Prime Minister Justin Trudeau whether he’d pursue a similar program for Canada, he remained evasive and said his priority would be ensuring that “there are no criminal elements” in the licensed producer system.

“As we look for licensing producers, we are going to do criminal background checks to ensure that this is being done responsibly,” said Trudeau, adding: “If someone is convicted of drug trafficking already, I don’t think we’re going to reward them with an opportunity to sell it legally.”

Dispensaries

In recent years, illegal marijuana dispensaries have opened up across Canada, even moreso since the Liberals came to power in 2015. Those who run them say the shops fill a void left by the licensed producer system, namely that they serve customers in-person, and offer products that the legal producers aren’t currently allowed to supply, such as edibles and concentrates.

It’s unclear what role dispensaries will have in the legal regime, as the federal government has left it up to the provinces and territories to decide how cannabis is sold.

Inside “416 Medicinal”, a dispensary in Toronto that was shut down during police raids in 2016.

In the experience of Jamie Shaw, a longtime dispensary advocate who’s the government relations director for MMJ Canada, the makeup of dispensaries owners would likely resemble most of the founders and CEO of the licensed producers — namely white men. She says she’s observed that a significant percentage of employees below that level are women and people of colour — although that’s nearly impossible to quantify, let alone compare that to the licensed producers, due to the a lack of hard data.

Jeremy Jacob, president of the Canadian Association of Medical Cannabis Dispensaries, is of the view that the dispensary — or grey market — system is easier to get into, therefore it allows for diversity among employees.

“Most of the cannabis business as it exists is small producers,” said Jacob. “They don’t really have the capital or the organizational wherewithal to take part in the LP program, so it’s cut out the majority of people who find it nearly impossible to become a producer.”

According to Shaw, there’s still a lot of work to be done among dispensaries, many of which prefer that their employees have clean criminal records, although most will overlook it if the employee faced cannabis-related offences.

“One tool we could use is tiered licensing, so depending on how much producers want to produce, then we could adjust the security and the entry requirements.”

“What I would like to see is some sort of merge between [the legal and illegal] systems,” said Shaw. “The customer base that you’re serving should look like your management team and if it doesn’t, then there’s a problem.”

While there are a number of grassroots initiatives to support women in cannabis businesses in Canada, there are few organized efforts to support people of colour in the field. In the U.S., there’s the Minority Cannabis Business Association, a national group founded in 2015 that describes its mission as creating “equal access and economic empowerment for cannabis businesses, their patients, and the communities most affected by the war on drugs.”

Its website goes on to state that “currently there are few minorities in the cannabis industry” and that “heavy regulation, high cost of entry, and information gaps hinder minorities from entering the industry.”

In the U.S., every state that has legalized medical or recreational marijuana has restrictions for people with drug records preventing them from working at a legal cannabis business, unless they meet strict criteria. And this, according to a 2016 Buzzfeed investigation, has perpetuated racial inequality. While there are no official statistics on race and cannabis business ownership in the U.S., the article found that about one percent of the 3,200 legal dispensaries across the country are owned by black people.

As for Canada, Valleriani says there’s still time to make the legal market more inclusive, while addressing the adverse impacts of criminalization.

“One tool we could use is tiered licensing, so depending on how much producers want to produce, then we could adjust the security and the entry requirements,” she said. “We can find creative solutions to address a lot of these social justice issues, which are really at the root of what reform is really about.”

Comments are closed.