The Eastern Cherokee were poised to dominate North Carolina’s cannabis industry. What happened?

From truthdig by Daniel Elkind June 1 2023

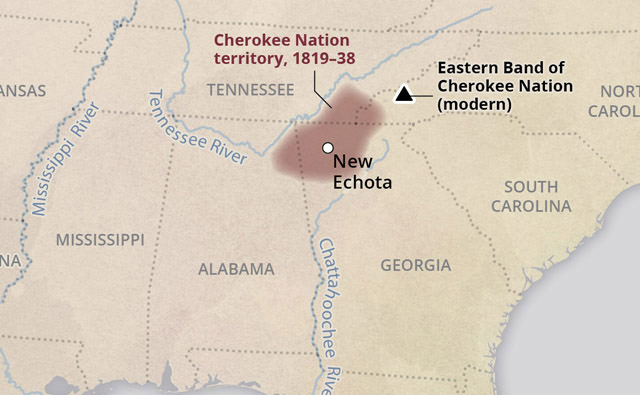

In May of 2021, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians legalized medical marijuana and decriminalized small amounts of cannabis. In one stroke of the pen, the tribe created an island of progressive drug reform in North Carolina, which like the rest of the greater South has lagged behind other parts of the country in modernizing cannabis laws. To establish a regional bridgehead in the multibillion-dollar cannabis industry, tribal leaders founded a company, Qualla Enterprises, tasked with cultivating marijuana plants at industrial scale within Qualla Boundary, the tribe’s 57,000-acre sovereign territory in the Great Smoky Mountains.

Two years later, the Eastern Cherokee people’s corner of these mountains aren’t as smoky as they’d hoped. Despite the success of an outdoor growing operation crowned by two signature strains — Qualla Bear and Goose Creep, the latter named for the slow onset of its effects — the business and regulatory pieces of the plan have stalled. The tribe’s Cannabis Control Board is accepting applications for medical licenses, only to file them into a void; no official timeline for production or sale has been unveiled. Founded in dreams of a swift rise to becoming a cannabis juggernaut, Qualla Enterprises has announced a hiring freeze. Meanwhile, state-level cannabis reform is moving forward, endangering every inch of the tribe’s head start.

Building a vertically integrated cannabis operation is a complex process anywhere, but it has proven especially nuanced for Native American communities in prohibition states like North Carolina. Although tribes like the EBCI are technically sovereign nations, their right to govern themselves is complicated by a murky web of economic and legal relationships and dependencies. At the center of this web is the federal government, which remains instrumental in tribal affairs. Washington licenses tribal casinos, subsidizes housing initiatives through the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Native American Programs and retains the power to enforce laws through a dizzying constellation of agencies. Although cannabis reform falls into one of many gray areas, tribes must reckon with federal drug laws, and carefully, in a way that protects their gaming licenses and federal assistance programs. The Qualla saga “highlights the challenges inherent in the exercise of tribal sovereignty,” writes the historian Ned Blackhawk.

Two years after the Eastern Cherokee broke ground on a cannabis industry, frustration with these challenges threatens to settle into resignation and regret.

“We just want to get the infrastructure we need to grow the product we need,” Forrest Parker, Qualla Enterprises’s general manager, told the tribal council in April. “Because if we can’t, we’re dead fish in the water.”

* * *

The Eastern Cherokee knew the risks. In 2017, four years before they founded Qualla Enterprises, Bureau of Indian Affairs officers raided a medical cannabis facility on tribal land in Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico, confiscating 16 plants. The raid took place after the tribe decriminalized cannabis and created a regulatory system according to the provisions of the law. In 2021, agents again raided Picuris Pueblo, this time targeting the home garden of a resident enrolled in New Mexico’s medical marijuana program to treat anxiety and PTSD.

The Obama administration tried but failed to prevent such raids. In 2013, then U.S. Deputy Attorney General James Cole issued a memo advising law enforcement and federal prosecutors not to disturb (locally) lawful growing operations on tribal lands without evidence that a crime is being committed on the premises.

However, the memo was never fully enforced, leaving state and tribal leaders caught in a game of legal pingpong. During his first year in office, President Donald Trump broke a campaign promise on states’ cannabis rights when he instructed Attorney General Jeff Sessions to rescind the Cole memo. Although the Biden administration hasn’t yet articulated a comprehensive federal cannabis policy, the Justice Department under Merrick Garland has signaled it expects to return to the terms of the 2013 directive.

In 2017, four years before they founded Qualla Enterprises, Bureau of Indian Affairs officers raided a medical cannabis facility on tribal land in Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico, confiscating 16 plants.

The Garland memoranda, though welcome, has not calmed the nerves of tribal authorities. In April, Mary Jane Oatman, a member of central Idaho’s Nez Perce tribe and executive director of the Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association (ICIA), told a webinar audience of tribal cannabis experts that tribes “will not get involved in the industry” while cannabis remains illegal under federal law, because they’re “afraid of losing federal support for housing and so forth.” Growing up on the Nez Perce Reservation during the 1980s, Oatman witnessed the effects of prohibition firsthand. Her grandfather and grandmother, a traditional healer, were raided and arrested by BIA and state agents for cultivating cannabis on tribal land.

Eastern Cherokee tribal leaders have sought legal clarity from state authorities to no avail. Earlier this year, the EBCI’s principal chief, Richard Sneed, pushed the North Carolina General Assembly to clarify and coordinate “the administration of medical cannabis laws across the jurisdictions of the State of North Carolina and Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.” He received no response.

Resolving this ambiguity has never been more urgent, as political winds favoring cannabis reform strengthen in the state capitol. The North Carolina senate recently passed the “Compassionate Care Act” with bipartisan support; if approved by the House, the bill would open the gates for non-Native cannabiz operations to compete with the Cherokee, who at the moment operate the region’s only legal cannabis farm. As well-established cannabis giants like Trulieve fill the marble halls in Raleigh with lobbyists, time is running out for Qualla Enterprises, whose officials anxiously monitor developments from company offices located down the road from Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort.

When asked about the tightening competition for first-mover advantage, representatives for Qualla Enterprises declined to comment.

* * *

According to the spirit and letter of laws granting tribes sovereign status, there should be no issue with the EBCI — or any of the roughly 50 tribally owned and operated cannabis businesses counted by Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association — raising capital for cannabis operations on tribal land. But in practice, sovereignty is a limited and evolving concept, under constant negotiation between tribal, state and federal authorities. Cannabis is only the latest site of these negotiations.

When it comes to doing business with state governments, tribal governments must enter into complicated legal relationships known as compacts. For many tribes, the most important of these compacts concerns the multibillion-dollar gaming industry that is their primary source of cash flow. The EBCI is one of 220 federally recognized tribes that together operate 360 licensed gaming enterprises across the country. In most cases, casino profits are evenly split between funding tribal operations, and payouts to tribal members. Last year, each member of the EBCI received a record-high $8,840 pre-tax check from the redistribution of casino profits. (In December 2020, Chief Sneed, signed a 38-page tribal-state gaming compact with North Carolina, countersigned by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, detailing the rules and regulations for casinos on EBCI territory.)

“This Tribe, like most gaming tribes, has become accustomed to a revenue stream that nothing in the world can touch, and that’s gaming,” Chief Sneed said in 2021. “Second to that would be cannabis. It’s imperative that we’re involved in emerging markets.”

This ultimate emerging market, however, is not worth risking established casino economies. Not surprisingly, caution has guided the National Indian Gaming Commission’s (NIGC) position on cannabis. The NIGC is a federal agency created by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 to oversee licensed casinos on tribal lands in partnership with the DOJ. When it comes to immunity from prosecution or penalties, however, it is not in a position to issue blanket protections to tribal gaming operations. Due to the federal scheduling of cannabis as an illegal drug, the NIGC has warned tribes away from funding cannabis projects with casino revenues. “The cultivation, sale and possession of cannabis is illegal under federal law and, therefore, net gaming revenue should not be used to finance such an operation,” the Commission wrote in an October 2021 guidance memo. It goes on to note that the Commission “is obligated to refer knowledge of [cannabis distribution on casino property] to the appropriate federal law enforcement agencies.”

The EBCI’s gaming authority has chosen to heed this advice. In a letter to Chief Sneed, it informed the council that, after “careful research of the existing statutes and ordinances regarding the use of distributable net gaming revenues,” it would not be funding Qualla Enterprises.

According to the spirit and letter of laws granting tribes sovereign status, there should be no issue with the EBCI — or any of the roughly 50 tribally owned and operated cannabis businesses counted by Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association — raising capital for cannabis operations on tribal land.

This wariness often leaves tribal cannabis enterprises in funding limbo. In the cases of Qualla Enterprises, the need to separate revenue streams has been the main cause of delays in securing the capital needed to get its planned state-of-the-art cannabis facility off the ground, according to multiple sources. The EBCI tribal council has raised $31 million for the cannabis project, or roughly one-third of what Qualla Enterprises says it needs to build a modern cannabusiness, but remains tens of millions of dollars short. For the remaining funds, it will have to acquire bank loans, which the tribe has agreed to cosign. Due to the federal illegality of cannabis, however, getting these loans has been virtually impossible. Since 2021, the company has repeatedly circled back to the tribal council with requests for the additional funds, only to be stymied once again.

In the latest round, an additional $64 million requested by Qualla was vetoed by Chief Sneed, jeopardizing the optimistic timeline of opening a dispensary in late summer or early fall. So far, company officials claim it has harvested a cannabis crop worth $20 million. But not a single gram of Qualla Bear or Goose Creep has been bottled or sold.

“We cannot go borrow the money from a bank,” Parker, Qualla’s general manager, told Smoky Mountain News in April, so long as marijuana “is federally illegal.”

* * *

In “The Rediscovery of America,” Ned Blackhawk traces the roots of federal-tribal paternalism to a landmark 1832 Supreme Court decision, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, which described the tribes’ proper relationship to the federal government as that of “ward to its guardian.” The Court ruled that tribes like the Cherokee were not, legally speaking, foreign states, but rather “dependent domestic nations,” in the words of Chief Justice John Marshall. A century later, New Deal-era reforms created more refined means of control by officials who “tied the prospects for land settlements to acceptance of policies designed to ‘terminate’ tribal sovereignty,” writes Blackhawk. It is a bitter irony that agencies tasked with safeguarding tribal sovereignty and self-determination have often contravened or undermined it in practice. In this they have often been assisted by state authorities. When sovereign nations attempted to end the BIA practice of sending Native children to foster homes in the 1950s, state and county authorities retaliated by ending welfare payments to tribal communities.

Seth Pearman, attorney general for South Dakota’s Flandreau Santee Sioux community, considers the modern practice of compacting inherently paternalistic in the Marshall mold. “You have to ask the state for permission for everything,” he told a recent webinar audience on the future of tribal cannabis. “Tribes are their own governments and that needs to be respected.”

This tradition of paternalism and the complexities of sovereignty may not be resolved in time to rescue the prospects of Qualla Enterprises. But creative solutions to such impasses are gaining traction among tribal cannabis proponents. One is the creation of a national sovereign market for tribal cannabis that would unite 574 federally recognized tribes and build on the longstanding tradition of intertribal commerce.

“Cannabis commerce between tribes has been happening for a long time,” said Oatman, of the Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association. “Now tribes are just looking for the guardrails that would allow them to operate in a legitimate manner.”

Whether federal and state authorities are willing to respect these guardrails remains to be seen.

Comments are closed.