The Caplin brothers are on the front lines of the Micmac fight for economic sovereignty.

By Dispensing Freedom

Near the mouth of the Restigouche River, between the border of New Brunswick and Quebec in the Bay of Chaleur, lies Ugpi’ganjig, or Eel River Bar First Nation. This Micmac* community belongs to the sovereign, unsurrendered land of the Gespegeoag district, and has long been a region of great economic value, enjoying a thriving fishing industry and abundant natural resources.

It was on the shores of this bay 489 years ago – on July 7th, 1534 to be exact – that the first documented trade exchange between Europeans and Indigenous people took place in Canadian history. French explorer Jacques Cartier was mapping the coast near Ugpi’ganjig when he was met by a flotilla of some 50 Micmac canoes. Sensing the possibility of an exchange of mutual benefit, and observing the Micmac willingness to trade, Cartier landed on the shore and traded iron knives, tools and clothing for Micmac furs.

Micmac people have lived on these lands since time immemorial, and they became allies and trading partners with the French in the 17th and 18th centuries. After the British conquered the French in the 1750s, the Micmac signed a series of peace and friendship treaties with the British Crown. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 applied on Micmac lands, and indicated that all land which had not been “ceded to or purchased by” the Crown was reserved to the Indians as “their Hunting Grounds.”

In the Nova Scotia Supreme Court ruling of R. v. Isaac, 1975 CanLII 2416 (NS CA) the court examined all the treaties made between the Crown and the Mi’kmaq people, and issued a finding stating that “No Nova Scotia treaty has been found whereby Indians ceded land to the Crown, whereby their rights on any land were specifically extinguished, or whereby they agreed to accept and retire to specified reserves.” In the decision, Justice MacKeigan stated that “I have been unable to find any record of any treaty, agreement or arrangement after 1780 extinguishing, modifying or confirming the Indian right to hunt and fish, or any other record of any cession or release of rights or lands by the Indians.” At the time of the 1763 Royal Proclamation, what is now known as the Province of New Brunswick was considered to be part of the Province of Nova Scotia.

The imposition of the racist Indian Act

However, with the industrial revolution boosting the population of landless paupers in Europe, a wave of mass migration to Canada of some 800,000 British immigrants took place between 1815 and 1850. This mass migration altered the Crown’s relationship with Indigenous people, and in 1867 the Dominion of Canada was created by the British North America Act. Intent on extracting the vast lumber, mineral, and animal resources on unsurrendered Indigenous lands, the new Dominion imposed the racist Indian Act on the Micmac and other sovereign Indigenous nations in 1876, and ignored the underlining Treaties and Aboriginal rights long recognized by the British Crown.

As researcher Joan Holmes notes, the Indigenous nations that made treaties with the Crown never agreed to the Indian Act. These nations “did not relinquish their authority or leadership, nor did they agree to abandon their traditional systems of political or social organization and self-determination. There is no record of them giving up the right to their spiritual and religious practices, nor did they agree to forfeit their freedom of movement. No First Nations agreed to submit to day to day management of their affairs by an outside government and none of the written accounts record any discussion of the Indian Act being applied to the signatory First Nations.”

The purpose of the Indian Act has always been quite clear. The 1884 version of the Act was subtitled “An Act to confer certain privileges on the more advanced Bands of the Indians of Canada, with the view of training them for the exercise of municipal powers.” In practice that meant repressing traditional governance systems and removing Indigenous people from their lands and concentrating them into small reserves which they were not allowed to leave without a pass from the local Indian Agent. In the 1940s alone, over 2000 Micmacs were forced from their homes, places of worship, and industries through this process. They were made to relocate onto “reserves” run under Indian Act control where they survived on minimal government handouts.

Across Canada, Indigenous people had their children stolen and put into residential schools. Thousands died, and the rest had their Indigenous languages beaten out of them as a way to “kill the Indian in the child.” Micmac people were harassed and imprisoned for hunting and fishing in their own lands, even as billionaire families such as the Irvings and their American millionaire buddies established exclusive hunting and fishing camps in their best fishing spots and profited from the clearcutting of Micmac forests.

Canada’s Indian Act Apartheid system was continuously resisted in a myriad of ways, both large and small. Language, culture and the traditional political systems survived by going underground. Some of the more pronounced forms of Micmac resistance took place in armed confrontations such as the armed standoff “Incident at Restigouche,” the extensive litigation of fishing rights through the Marshall case, resistance against Alton Gas, and struggles for fishing rights at Burnt Church. These conflicts are woven together by a common thread, the economic rights of the Micmac people to hunt, fish, and trade – rights which they were clearly exercising when they met Jacques Cartier 488 years ago, and which they continue to hold and exercise today.

Caption: Kyle Caplin (left), and Cody Caplin (right) and three friends outside of the Ugpi’ganja truck house in Eel Bar River.

On the front lines of Micmac economic sovereignty

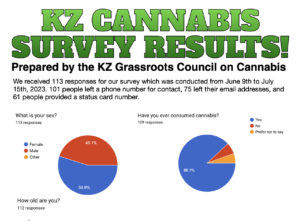

Chris, Kyle and Cody Caplin are brothers who live at Ugpi’ganjig and who have been on the front lines of the Micmac fight for economic sovereignty for years. Like hundreds of other Indigenous entrepreneurs, when Canada legalized cannabis in 2018, Chris and Cody Caplin opened a sovereign trading post to sell cannabis on reserve. With wide ranging support for the use of cannabis as a medicine in the community, five other cannabis shops followed the lead of the Medicine Cabinet, and have helped to build a thriving cannabis economy in the community.

Even though the Eel River Bar reserve is located on unceded lands not subject to Canadian cannabis laws, on March 26th, 2021 the RCMP raided the Medicine Cabinet. The shop was located on the same lot as the family home, and father Dean Caplin had recently had a stroke and was sick in bed when the raid happened. According to Cody, a “special forces type officer dressed in all green fatigues” unholstered his gun and pointed it right at Dean. Dean was then dragged out of his bed in his underwear without even having a chance to get dressed. Taken outside in the cold, Dean lost consciousness and collapsed in the RCMP cruiser. The RCMP ignored Dean’s health crisis, and an officer slammed the door of the cruiser and said “it’s ok, he’ll be fine.” Eventually, an elected Band Councilor called an ambulance for Dean and he was taken to hospital in it.

According to Cody, “the RCMP raided the whole house and searched everywhere.” The RCMP left with more than $60,000 worth of cannabis products, four rifles and shotguns used by the family to hunt, Interac machines, cash and a cash box. The brothers, their father and a worker at the shop were held by police for over 10 hours before being released. Chris Caplin came forward to take all responsibility for the cannabis shop, however Cody and his father Dean were also charged, although the charges were later dropped. Chris Caplin, is still charged with “possession of a unregistered firearm” and “unsafe storage.” However, as of today he has still not received the paperwork for the disclosure in the case and his guns are still in the possession of the RCMP.

Community members in Eel River Bar rallied around the Caplin family, and were shocked at the raid. According to Cody, “We got a lot of community support, including some Band Councilors. Even Chief Sacha Labillois showed up and freaked out on the RCMP to try and look good, but in fact, it was her that set the whole thing up.”

A year later, all cannabis charges against Chris were dropped as he prepared a constitutional challenge to the raid. According to brother Kyle, “I went into the police station for a criminal record check, and the RCMP liaison Guy Savoie let me know that all charges were dropped on us. He apologized for the raid, and said that Chief Labillois was the one who called in the RCMP and signed a letter to let the police take action on reserve to raid us for selling hard drugs like cocaine.”

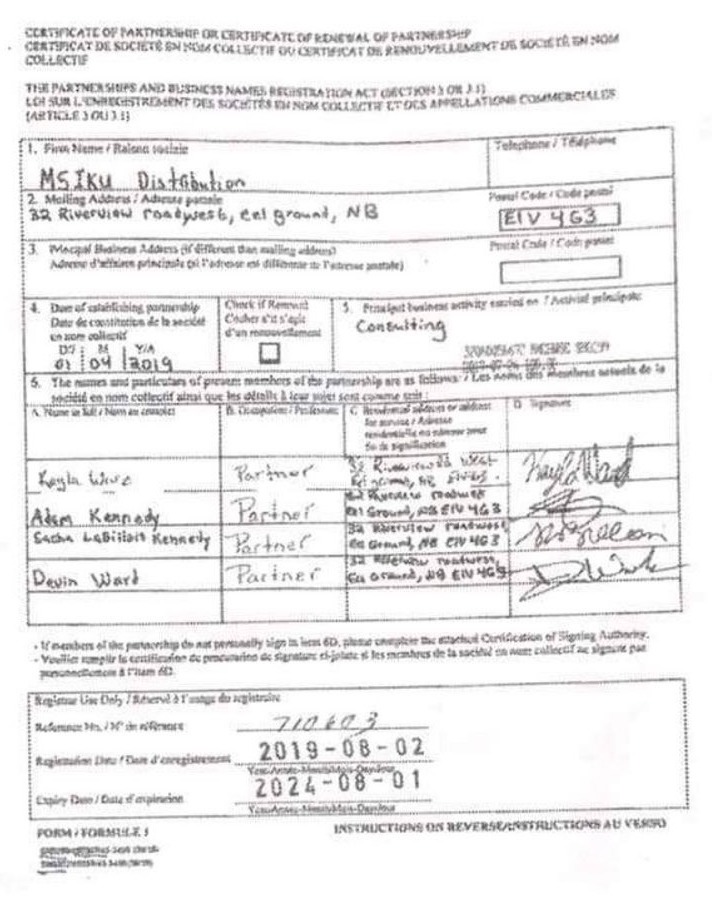

The irony of the raid was not lost on the brothers. According to Cody, Chief Labillois owns her own cannabis distribution company named “Msiku” – “grass” in the Micmac language. According to Cody, “I have documents that prove she owns it. She has line of cannabis flower in cans that she’s trying to sell to shops.” [Chief Labillois and the RCMP media liaison for Guy Savoie were contacted and asked for comment but have not responded to our requests.] After the raid, Cody recalls that the Chief’s husband Adam Kennedy came to him to offer to sell Msiku cannabis products with a display stand in his store. Msiku is not a licensed producer of cannabis in Canada, so in the eyes of the government it is just as much “black market” as any other form of “illicit” cannabis.

Despite dropping the charges, the RCMP did not return any of the $60,000 in cannabis products they stole. “They said our product was destroyed because it’s not been stamped,” said Cody. They broke in, stole our stuff. We had no court dates, no justice, no nothing,” added Kyle.

The Caplins live their lives as Micmac people. They are self-employed and work in variety of different ways. In the fall they fish for lobster, in the summer for salmon, in the summer they do construction with Cody’s Iron Horse roofing and construction business. This simple intention to live life on their own terms, in their own unceded lands, has led to constant and ongoing problems with the local RCMP and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Canada fails to uphold its own Supreme Court Rulings

In 2015 Kyle and Cody Caplin began to fish for eels and salmon in their traditional waters in 20 foot salmon skiff. As soon as they began exercising their rights – rights upheld by Canada’s own Supreme Court in the 1999 Marshall decision and protected by Sections 25 and 35 of the Canadian Constitution – they say that they came up against the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). As Kyle notes, “when we started exercising [our rights], that’s when we became the problem. We were the bad guys to the DFO and the government. They were always harassing us and stealing our gear and making racist comments. When it came to fishing, they would take our traps every day. We never did anything wrong. We were out there trying to provide for our families. They’re trying to make us look like bad guy criminals.”

On September 12th, 2018 the brothers were out fishing for lobsters for food and ceremonial reasons as per their rights. Unbeknownst to them, DFO officers were surveilling them from a distance. As soon as they landed on shore, a SWAT team came running at them with their hands on their guns and arrested the brothers. The cops drove off with their lobsters, boat, and a trailer. Charges weren’t laid until a year later, when the brothers were charged with illegal fishing and fishing in a “closed” zone.

In the absence of receiving any charges, and wondering what was going with their boat and gear, the brothers showed up at the local DFO office to ask for their property back. As soon as they arrived, they were profiled as “dangers to society.” As Cody says, “they tried to paint a picture that we were going to hurt them when we went to the DFO to retrieve our boat. They had their hands on their guns, they pressed the emergency button. They tried to claim we were “boxers.” We used to box when we were kids – 13 years old – I’m 45 years old now! They’re trying to make us look like criminals.”

The racist harassment and abuse directed at the Caplin brothers is standard operating procedure for the DFO. According to a 2021 article by Zoe Heaps Tennant in the Walrus Magazine, “Fisheries officers have been known to go undercover, to slip out onto the water in the middle of the night to microchip lobsters in Mi’kmaw fishers’ pots in order to try to trace the shellfish. Less covert operations include seizing Mi’kmaw fishers’ traps, catch, boats, and even trucks.”

Tennant adds that in hotspots like Esgenoôpetitj (Burnt Church First Nation, New Brunswick) “Fisheries and RCMP officers, some dressed in riot gear, were reported to have used batons, tear gas, arrests, raids, and trap seizures to stop Mi’kmaw fishers from operating. Indigenous fishers told reporters at the time that DFO officers had pointed guns at them…. One widely circulated video, shot in Miramichi Bay, showed a large government vessel speeding up and running over a small Mi’kmaw fishing boat, forcing the fishers overboard, and then gunning for their vessel again. One Mi’kmaw fisher later described being pepper sprayed by officers while he was still in the water.”

It is obvious that Caplins and other Micmac fishermen shouldn’t be facing this kind of state repression for exercising the rights. Micmac people fishing and harvesting from their unceded lands and waters is an obvious and uncontested Aboriginal right that was enshrined in the Peace and Friendship treaties the Micmacs made with the Crown. The Micmacs were clearly hunting and fishing before Jacques Cartier showed up to trade, and the point is worth stressing that they never surrendered that right, or any of their lands to any other nation.

The Micmac right to fish was supposedly definitively resolved by the 1999 R. v. Marshall Supreme Court ruling which acknowledged that Micmacs had Aboriginal and Treaty rights to hunt and fish on their lands and declared that the Micmac had the right to earn an undefined “moderate livelihood” for their efforts. However, as soon as the court decision came down, Canadian politicians acted to undermine the affirmed treaty rights.

The Federal Government did so by in effect negotiating a fishing agreement with itself. Indian Act Band Councils are government departments funded by and responsible to the Minister of Indian Affairs. The Feds made a deal with their own institutions, provided those institutions with hundreds of millions of dollars, and then used them to implement a fishing regime that went against the Aboriginal and Treaty rights of the Micmac people themselves.

The deals made by the Feds after the Marshall decision were called Rights Reconciliation Agreements (RRAs) but as Zoe Tennant points out, “These deals were not an implementation of the [Marshall] ruling: they didn’t address treaty rights. Instead, in exchange for commercial licences, federal funds, and training, bands had to assimilate into existing DFO regulations. The same regulations that Marshall had fought, and won, to be exempted from.”

As is typical for Band Council agreements, the actual content of the deal is confidential and hidden from the public. The Micmac people were kept out of the negotiations for the agreements and have had no say in having their rights again ignored.

On October 13th 2022, the brothers sat down for a conversation with former National Chief Del Riley, Micmac Hereditary Chief Nick Prisk, and Putus Hector Pictou, a former National Chief for the Atlantic Region. In reflecting on the Marshall decision, Pictou noted that “when that court case was made public, Jean Chretien put an interim fishing agreement on the table with $159 million dollars attached to it.” As Pictou explained, the real problem lies with the Indian Act Chief and Council system, which while literally registered as a municipal corporation under the Provincial system, pretends to be a “First Nation” with Treaty and Aboriginal Rights. Kyle Caplin concurred, adding “all of this wouldn’t happen if our band council didn’t sign that FSC [Food, Fishing and Ceremonial] agreement” with the Federal government.

Chief Del Riley, the former National Chief of the Indian Brotherhood who negotiated the inclusion of Sections 25 and 35 of the Canadian Constitution views the Federal Government’s FSC deal with Band Councils of being of little use. “That fishing agreement is irrelevant. You’ve got two Federal agencies making a deal. The only thing that counts is your Treaty because it was made before, and it doesn’t restrict you to anything. The [FSC] agreement doesn’t affect your Treaty. They can’t change the Treaty with that agreement, it applies to everyone – not their Federal agreement. It’s protected under the Constitution. That [FSC] agreement, the only thing it can do is comply with the Treaty. The treaty is superior. Section 35 is superior to their agreement, no matter what they did.”

This perspective makes complete sense to Hereditary Chief Nick Prisk. He explained the situation as follows. “Natives owning this land is legitimate and rule following. Natives owning this land is in keeping with the rules of justice. There never was a legal transfer of Mi’kmaki to the Crown. The Crown claiming native land is not justice preserving. An unjust acquisition equals an unjust holding. They got this country illegally, so they don’t have a legal holding to it. Unjust acquisition plus a just transfer equals an unjust holding. That has happened. Unjust acquisition plus unjust holding equals an unjust holding. That has happened. Just acquisition plus a just transfer equals a just holding. That has never, never, never happened. And at that point you ask them to show you title to this land that meets this criteria and they are not going to be able to do it.”

Lawsuits and a constitutional question

Originally represented by lawyer Liam Smith from Nova Scotia Caplin is now representing himself in a constitutional challenge to defend himself against the DFO charges. His legal argument seeks “an order to declare as unconstitutional and of no force or effect” nine different conditions and regulations in the 2018-2019 Eel River Bar First Nation Aboriginal Communal Fishing License that Band Council agreed to with the Federal government. The rules that Caplin is seeking to declare as unconstitutional are those which prohibit “designated fishers from catching and retaining lobsters of a size of less than 77 mm;” the condition that “designated fishers to affix a tag, float, or buoy to each end of the fishing gear;” the prohibition to fish for or possess lobster in lobster fishing area 23(a) – the water adjacent to Ugpi’ganjig Eel River Bar First Nation;” the prohibition to have a trap on board a vessel, in lobster fishing area;” and, “The prohibition to fish for lobster without authorization.”

Ultimately, Caplin is arguing that all “the main constitutional issues raised by this matter are res judicata, having already been decided by the Supreme Court of Canada in favor of Mi’kmaq” in the Marshall decision. Caplin argues that he “enjoys a limited immunity from prosecution under the impugned provisions of the Fisheries Act and Regulations in this matter, based upon his Mi’kmaw treaty rights to fish, notably the treaty rights to fish contained in the Mi’kmaq – Crown Treaty of 1760 – 61, his aboriginal rights to fish, and the protection afforded by s. 35 (1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.”

Caplin is also part of a group of Mi’kmaq fishermen who are planning to launch a class action lawsuit against the Canadian government, claiming that the federal government has not “come close to satisfying its obligations to the Mi’kmaw people.”

Dispensing Freedom will continue to cover this case and will bring you further news and updates from Ugpi’ganjig as this matter unfolds.

*Note: We are using the older spelling of Micmac rather than the more recently introduced Mi’kmaq spelling in accordance with a request from former Atlantic Region National Chief and Putus, Hector Pictou, who explained that it was only after the government paid Bruce Wildsmith, a Law Professor from Dalhousie university, $2.5 million to represent Donald Marshall, that the term Micmac became spelled as Mi’kmaq. According to Putus, “The term Micmac is ours. It didn’t come from a court transcript, it’s our every day way to spell our identity, and it is the name on the treaties that were signed with our sovereign ancestors.”

Comments are closed.