From cannabiswire.com link to article by Julia Barajas, Sept 6th 2019

Canada’s Assembly of First Nations, representing more than 900,000 indigenous people south of the Arctic Circle, held its first-ever National Cannabis Summit in Vancouver this week, where participants discussed the implications of legalization on the safety, public health, and economic development of their communities.

In a statement announcing the summit, the advocacy group, which represents 634 of what are known as First Nation communities, said that the two-day summit was meant to give a voice to those who feel they have been excluded from the national cannabis conversation. Organizers also said they tried to supply “the best and most current information on all aspects of legal cannabis so First Nations can make informed decisions.”

According to the Assembly, when the Cannabis Act was implemented last October, “The federal government did not fully engage or consult with First Nations on how its proposed legislation would ensure respect and implementation of First Nations rights, title, and jurisdiction.”

To this end, during question-and-answer portions of the events, members of the audience discussed asking the federal government to amend current cannabis legislation “to create a specific space for First Nations,” in addition to potentially forging an alliance “to assert the rightful, legitimate, and legal place of First Nations jurisdiction.”

Caught between borders

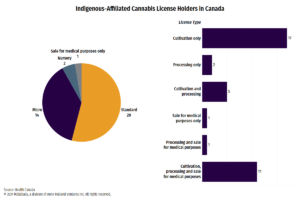

During a session on cannabis business ventures, Loraine White of Seven Leaf, “the first 100% Indigenous owned and operated cannabis producer licensed by Health Canada on First Nation territory,” noted that the company’s executive team is wholly comprised of Mohawks from Akwesasne and that 98 percent of their employees are also of the same origin. Their production facilities, she added, are built on Akwesasne Mohawk land, which encompasses Ontario, Québec, and part of New York. This is significant, she explained, because the facilities are located on an island “with the alleged international borders bisecting our community,” which, though governed and authorized by Canadian federal government, “will be owned and operated by Mohawks.”

As a possible result, it took Seven Leaf nearly five years to get its license, White added. “It’s safe to say that we were the longest pending Health Canada application in the history of the agency.”

Lessons from alcohol

However, not all First Nations want to welcome cannabis. During day one of the event, participants echoed National Chief Perry Bellegarde, who said that “First Nations have diverse views on legal cannabis” and that the Assembly will “fully support those First Nations who do not want to participate.”

Meanwhile, on the second day of the event, Carol Hopkins, executive director at the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, a non-profit that works with people in First Nations who struggle with substance use, warned against crafting bylaws banning cannabis. Nearly a decade ago, she said, the foundation conducted a study on the bylaws banning alcohol in Canada’s First Nations. Among almost all of the nations surveyed, said Hopkins, the policy was found to have “absolutely no effect.”

Laws banning alcohol, she explained, were largely “created in the context of community crisis,” such as a death in the community or the detection of “significant harms,” which “created pressure on the community governments to do something.” However, because public health in First Nations is underfunded, Hopkins added, the implementation of these bylaws ultimately became the responsibility of the police force, a situation that did nothing to resolve the underlying issues that generated the crisis in the first place.

“I mention that history because that’s the same response that is coming up in the conversations about cannabis,” said Hopkins. “The prohibitionist philosophy has no effect. It does not stop the substances from coming in to our community. It drives it underground, and it’s still available to the most vulnerable populations.”

Later that day, Nel Weiman, who serves as Senior Medical Officer at the First Nations Health Authority, which is responsible for administering health programs and services for indigenous communities in British Columbia, agreed with Hopkins, underscoring that “prohibition is not an effective public health strategy.”

Weiman also spoke to the impending legalization of sales of edibles and cannabis derivatives (extracts, ointments, oils, etc.) throughout Canada in October. To prepare, she said, the First Nations Health Authority is “sending out out messaging like, ‘Start Low and Go Slow,’” which is especially directed at the consumers of edibles because they take time to kick in.

Other sessions throughout the day focused on topics including opportunities in ancillary markets, and cannabis use in harm reduction.

Comments are closed.